I am one of an estimated 70,000 Indigenous people living in Toronto. And while there is a variety of social services spaces like the Native Women’s Resource Centre of Toronto, Miziwe Biik Aboriginal Employment and Training, Toronto Council Fire Native Cultural Centre, and a handful of businesses sprinkled throughout the city, like restaurants Tea N Bannock in Gerrard India Bazaar, and Pow Wow Café in Kensington Market, there is no defined space for Indigenous people. While people from the Greek diaspora can find the dishes their yiayia used to make and support business owners who’ve immigrated from their home country, that kinship doesn’t exist for the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people.

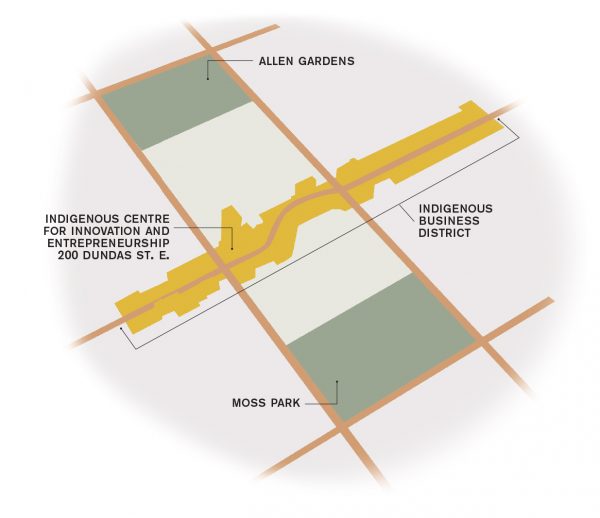

But Toronto City Councillor Kristyn Wong-Tam is looking to change that, with a business incubator and accelerator — The Indigenous Centre of Innovation and Entrepreneurship (ICIE) — that aims to spark an eventual Indigenous business and cultural district — the first of its kind in Canada.

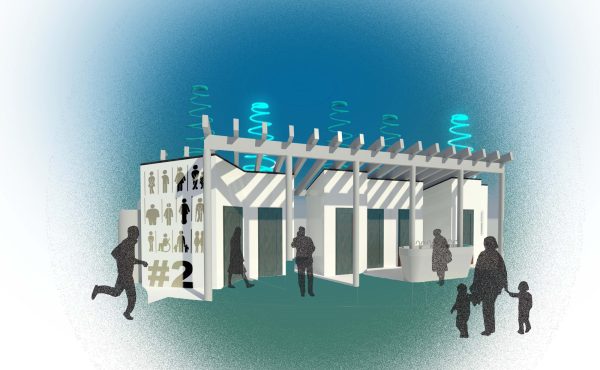

After working with an Indigenous consulting firm, Wong-Tam learned that, while an Indigenous district would be a worthy pursuit, it needed a large space to bring people together first. Enter the ICIE, a 16,000-sq. ft., City-owned building at the corner of Jarvis and Dundas streets. When it opens its doors in 2020, it will bring together Indigenous business owners, innovators, culture makers, and entrepreneurs.

“Consider the irony — the First Nations people of Canada’s biggest challenge of creating a district was real estate,” says Wong-Tam. “We wanted to create that real estate for them for the use of the Indigenous community and the people who want to do business with them.”

In addition to small business space, there will be programming, mentorship, and networking opportunities for participating entrepreneurs to scale up their skills and their business.

“The Indigenous youth and new business start-ups tell me that conventional models of start-ups don’t work for them,” she adds. “They want to be able to grow their business in a space that is culturally appropriate, but at the same time be able to access the tools that are available in other spaces where they don’t feel comfortable.

JP Gladu, president and CEO of the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, says he’s been working with Wong-Tam for a few years on the initiatives, alongside the Mississaugas of the New Credit Nation’s Chief Stacey Laforme. (The City of Toronto sits on that nation’s land.)

According to national research done by the CCAB, Indigenous people contributed about $12 billion in business in 2016, across the country. There are over 40,000 Indigenous businesses in operation in Canada, and a growing Indigenous economy and entrepreneurial base.

Gladu hopes the business incubator will be a place to shatter the myths about Indigenous people as business owners that “we don’t know how to run a business, that we struggle — many of the socio-economic indicators point to lowered life expectancy rates, education completion rates, you name it. So Canadians haven’t really had an opportunity to see what we’re capable of.”

Toronto’s innovation wouldn’t necessarily work in other Canadian cities, which each have their own complicated relationship to their Indigenous population.

Edmonton is within Treaty 6 territory and, according to the 2016 Census, has the second largest Aboriginal population of any municipality in Canada, including First Nation, Inuit, and Métis people.

Edmonton is currently in the development stage for an Indigenous culture and wellness centre, which includes determining in collaboration with Indigenous communities, what functions they want to see it serve. There’s also the outdoor ceremonial and culture site, Kihciy Askiy, that’s going into construction this year. With about 2.5 hectares and four sweat lodges, it will provide a setting for ceremonies, growing medicinal herbs, and creating traditional crafts, and will be available to the general public to provide education about Indigenous traditions, when it opens next spring. The project is a partnership between the City of Edmonton and the Native Counselling Services of Alberta.

Despite a number of Indigenous-aimed spaces in the works, Mike Chow, director of Indigenous Relations for the City of Edmonton, says he doesn’t think the City is quite there yet. “It’s unfortunate that Alberta has this view of being redneck or of social conservatism,” he says. “To not acknowledge that we still have these challenges and incidences that take us backwards … we have to stay vigilant.”

He adds that working with Indigenous communities is a tremendous opportunity. “If people are leaving reserves for opportunities like post-secondary education or employment, wouldn’t we rather them come to Edmonton than anywhere else? It makes sense from a diversity and economic perspective to make the city hospitable,” says Chow.

Meanwhile, in Vancouver, City Councillor Andrea Reimer says the City has a dynamic and complex relationship with its local First Nations, including three overlapping claims to the territory and no treaties.

The City works closely with the MST (Musqueam Indian Band, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations) Development Corporation on residential and commercial planning for a tract of undeveloped land in the city.

“We’re looking at community benefits agreements to see how their community members will be employed, and the [Vancouver International] airport is the first that we’re aware of in the world with a revenue sharing agreement with the Musqueam, because the airport sits on their territory. That’s pretty revolutionary in the context of reconciliation,” says Reimer. She adds that they’re also working together on fighting the Kinder Morgan pipeline.

She thinks replicating the Indigenous District that Toronto is proposing would be complex in Vancouver — there’s the lack of treaties with reserve lands, three nations working to settle the issue of their title and rights to the land — but not impossible. “It’d be a long way down the list.”

While the City has over 100 initiatives they’re currently working on with the nations in and surrounding Vancouver — including Indigenous design guidelines, statements of acknowledgment of land, and an Indigenous Fashion Week — Reimer says that the City, the First Nations territories, and the urban-dwelling Indigenous people “are virtually making it up as we go along.”

“I’ve looked all over the world and there is no manual for reconciliation,” says Reimer. “This is not a time for the government to say, ‘just trust us,’ but every single time we put an invitation to the community to engage in this work, the main overwhelming response is ‘thank you for making the space’.”

She says that this unstructured alliance has lent itself to a lack of documentation, and she adds that if you want to hear about it, you’ll have to find a storyteller, which, ultimately, is a very Indigenous thing to do.

“One of the main things we hear from the three nations that Vancouver sits on is how profound the experience of being erased from their own territory has been — culture, language, visibility — so we’ve worked really hard on over the last few years as the relationship has deepened,” she says. “That’s the next mountain we’re climbing is how to make visible again the three nations.”

Renderings courtesy ERA Architects; the City of Edmonton

This story originally appeared in Spacing issue 47, Summer 2018.

This story originally appeared in Spacing issue 47, Summer 2018.