In the 48 hours since Sidewalk Labs’ Master Innovation and Development Plan dropped, we have all been working our way through its 1524 pages, watching as the pile of important questions continues to grow. Mine have to do with the role of government.

Since this project was announced on October 17, 2017, a troubling seed was sown: `government is broken, but don’t worry, we’re here to fix it.’ The Innovator-as-Superhero role is a common one when technologists come to town and Toronto’s experience so far is no exception. In the weeks preceding the MIDP’s launch, a number of prominent urbanists and community leaders expressed their public support for Sidewalk Labs’ innovative efforts. I feel it is important to assert, right here and right now, that we need to de-couple our desire to be innovative from the companion assertion that government isn’t up to the job.

Yes, we can be innovative, but governments have important roles to play.

It’s easy in Toronto to find people who will argue that City Hall is mired in red tape, that it is slow moving, short-sighted, or fragmented in its work. These sentiments provide fertile ground for technology vendors whose business model is based on selling people on their ability to un-stick government and get things done. This is a sales pitch, and we should take heed accordingly.

The point here isn’t to argue that government is perfect and nothing needs to change. In the smart city landscape, government is often a partner with the private sector so we need to keep our collective eyes on government to ensure the public interest is a top priority. The work of improving government is perpetual. In a city as complex as Toronto, there is plenty of room for improvement. Progressive governments have many projects underway to improve their responsiveness, efficiency, transparency and inclusiveness. We need to support these efforts, not undermine them by pulling the rug out from under government and giving it over to tech firms.

Doubling down on our support for government is particularly important when policy-makers are grappling with smart city projects. The scope and complexity of the MIDP’s propositions needs thorough interrogation by everyone, especially officials in all three orders of government. Sidewalk Lab’s plan asks us to be innovative and embrace risk so we can have a better future. But are the solutions they are proposing aligned with our most pressing problems? Are the risks and concessions Sidewalk Labs wants us to take worth it? Waterfront Toronto will talking to the public about the Plan in July and the City will follow with their own events later this year.

The process by which we work through these questions requires a stable and robustly resourced government. These questions are of great civic importance and the discussion about answers needs to take place in public, adjudicated by elected officials.

It is humbling to admit that a big lesson we’ve learned so far in this process is that we, as a city, weren’t ready for a smart city conversation like this one. This project is a messy mirror reflecting how much work in real time we need to do build both capacity and the governance structures we need to effectively respond.

So here we are, work is underway and let’s go.

Given the intensity of attention this process and the plan are receiving, it is easy to think we’re alone in this space, forging new ground. While our experience with this vendor is unique, we’re not the only ones working on complex smart city efforts. In May, the Government of Canada awarded its Smart City Challenge prizes. The City of Montreal won $50 million for its community-centred process to improving mobility and food security. The City of Guelph partnered with Wellington County and won the $10 million prize for its circular food economy proposal. Guelph’s Civic Accelerator created a new space to frame new ways to work with city hall. These projects, like the others in the Challenge, are led by local governments.

The City of Boston has its Office of New Urban Mechanics to explore new ways of working inside government. Check out their “Smart City Playbook.” It informs vendors “to stop sending sales people” and tell the city officials “who [they] have spoken to in Boston before coming to us.”

Barcelona, a world leader in the smart city space, doubled down on inside-government efforts to defend the public good and create a platform for innovation. Amsterdam has built a different type of smart city governance infrastructure, but here again there is a strong-government/public good centering of the work. New York, London and Boston have teamed up for Cities for Digital Rights. Its declaration is clear — that city leadership is imperative to protect human rights as smart city technology is adopted. These governments aren’t lost or stuck; they are innovative, bold and leading.

To the skeptics thinking, `well, that all worked elsewhere but Toronto isn’t Barcelona,’ I’d say hang on. The City of Toronto has a long history of municipal innovation and leadership. Toronto led the world in 1988 with its municipal action plan for climate change. The City’s experiment with performance-based zoning in the Kings (East and West) was ground breaking and fundamentally changed our city. We have the Bentway because of the generosity of philanthropists, keen urban advocates, and the creation of the special inside-City Hall working group to help put that donated money into play in the right away. And Tower Renewal is pushing new place-based solutions.

The June 6th report to the executive committee outlined the Waterfront Secretariat’s approach to receiving the MIDP. Councillors Paul Ainslie and Joe Cressy, meanwhile, are leading Toronto’s charge to sign the Cities for Digital Rights Charter. Toronto can be innovative and smart city action is underway. Let’s keep building, talking and doing.

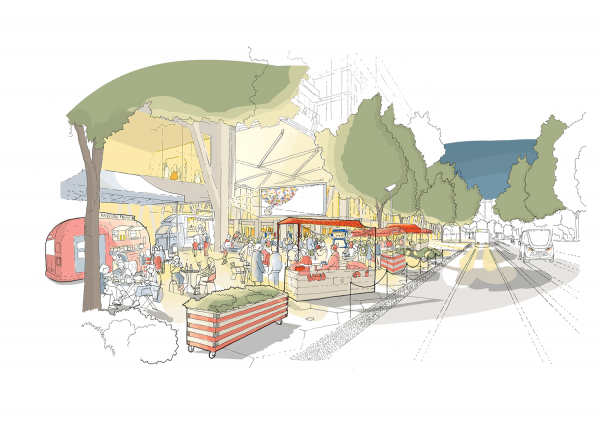

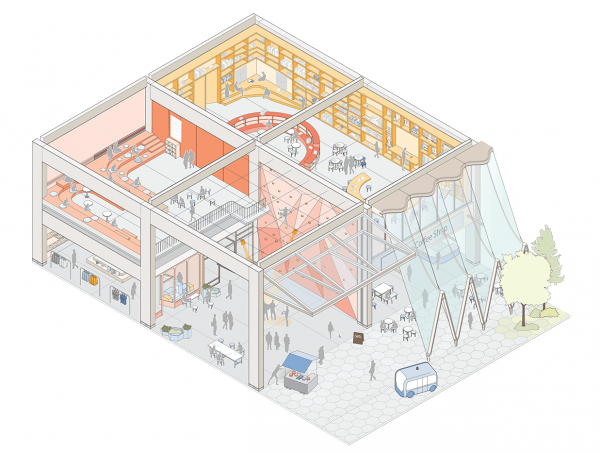

The 18-pound boxed-set draft MIDP presents Sidewalk’s vision of Toronto Tomorrow. We can’t democratically and inclusively talk about who funds the LRT or the IDEA District or data governance or whether the risks this project asks us to take are worth it unless we start with the fundamental premise that the government has a strong role to play.

There is no smart city without strong government.

Pamela Robinson is the incoming Director of Ryerson University’s School of Urban and Regional Planning and a Spacing contributing editor. She is a member of Waterfront Toronto’s Digital Strategy Advisory Panel. The views expressed here are personal and do not reflect those of the Panel or Waterfront Toronto. Follow Pamela on Twitter at @pjrplan