I am probably the last person you would expect to be perusing Communist literature. I come from a family of Mounties. I have worked on Bay Street. I have spent almost my entire adult life in the Canadian Army, where some of our finest Cold Warriors initially trained me.

Communists, I had always been taught, were the bad guys and no one in their right mind should clutter their head with trying to understand them. But now I am an historian, which means that I (or really any curious human being) try to understand how another person sees the world even (especially?) if you do not agree with them.

My entry point for this line of inquiry was the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). It is a tragic and fascinating conflict, made even more interesting by the presence of nearly 1,700 Canadians who made their way to Spain secretly, and, by the summer of 1937, illegally. I studied the commander, Edward Cecil-Smith, a Toronto journalist who had been a stalwart of the Communist Party press. My book on his life, Not for King or Country, is coming out this winter. Now, I am working on a book about William Krehm, a Toronto Trotskyist who created his own organization, the League for a Revolutionary Workers Party, and was in Barcelona with George Orwell in the spring of 1937.

Suffice it to say, I am now up to my eyeballs in the Communist documents I never thought I would touch. And if you want to study such things, you have to go to the Toronto Reference Library (TRL).

The Toronto Reference Library has an outstanding collection of interwar year Communist newspapers, much on microfiche and some in its original paper form. These documents are black and white, but full of metaphorical color. They are contrarian and cover events that do not get much space in the mainstream newspapers. And they are reasonably short, giving the reader a snapshot of the editors’ priorities instead of a mass of detail through which to wade. Some have photographs, most are decorated with distinctive linoleum block cartoons.

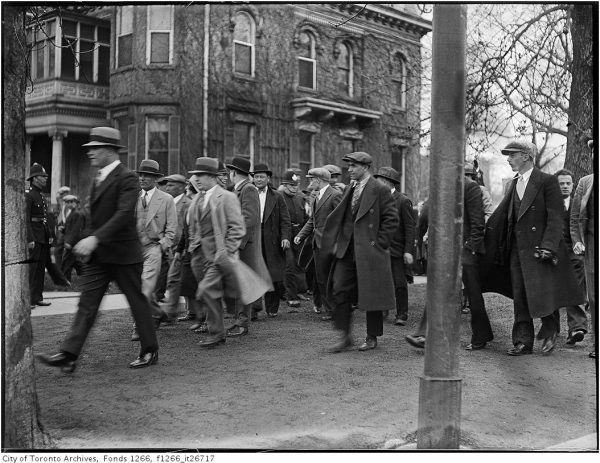

The newspapers were prepared on a shoestring budget, but they still managed to have correspondents in interesting parts of Canada and the world. “Workers’ Correspondents” reported from various picket lines and altercations with police. The Daily Clarion had two correspondents in Spain during the war (Myrtle Eugenia “Jean” or “Jim” Watts, and Ted Allan — later nominated for an Academy Award). The paper published a number of letters home from the volunteers in the International Brigades. Pat Forkin reported extensively from Moscow where he was also receiving treatment for tuberculosis. Norman Bethune published two articles in the Clarion while he was in China.

The “family tree” of Canada’s Communist newspapers

The Worker was the first newspaper, printing every few weeks or months until it became a thrice-weekly production. It continued to publish even after the courts outlawed the Communist Party in 1931. In 1936, the Communist Party transitioned to a much more professional looking newspaper, The Daily Clarion, which became a richly illustrated weekly news magazine in 1939 until the War Measures Act outlawed the party yet again during the Second World War. The Daily Clarion and The Clarion are much softer in their tone than the fiery Marxist-Leninist language found in the pages of The Worker.

In the same timeframe, the party’s front organization produced fascinating periodicals. The Progressive Arts Club printed Masses, which provides a rich source of literary criticism, news regarding censorship, scripts for plays, short stories and poetry (including a few great ones from future officer of the Order of Canada, Dorothy Livesay).

Labor Defender, the magazine for the Canadian Labor Defense League, is a great source regarding legal issues of the day ranging from the trials of the Communist Party leadership to the Scottsboro Boys in the United States. The Friends of the Soviet Union’s Soviet Russia Today is another great periodical, but for that you will have to visit the Kenney Collection at the University of Toronto’s Thomas Fisher Rare Books Library for hard copies, or check out this link thanks to a research project by Professor Kirk Niergarth of Mount Royal University. Edward Cecil-Smith wrote in and edited all of these different periodicals during the 1930s.

Each of these periodicals can tell a lot about life in the 1930s, but one should not read them in isolation. The reports are more than a little one-sided, although the slant does not necessarily make them wrong. The writers present a tonne of conspiracy theories about the government’s manipulation of the working class, and the papers uncritically passed along the rosy propaganda (and often outright lies) coming out of the Soviet Union.

But the editorials are intriguing, the news is always from a different point of view, and the advertisements and features reveal a vibrant workers’ culture that is not otherwise recorded. It also provides a useful tonic to the revisionism that the Communist Party dabbled in during the Cold War; the contemporaneous newspaper accounts often directly contradict the memoirs later written by party leaders.

Next time you want a different perspective on the city during the Dirty Thirties, take a peak at the TRL’s collection. These newspapers will reward readers with a whole host of interesting stories that never made it into most history textbooks.

Tyler Wentzell is the author of Not for King or Country: Edward Cecil-Smith, the Communist Party of Canada and the Spanish Civil War, forthcoming from the University of Toronto Press and available for pre-order now.