Note: At the end of November, I was part of a panel hosted by the Institute for Municipal Finance and Governance on “Does Toronto Need a City Charter?” This column is an edited version of my comments on that panel. Another version will be coming out in an IMFG publication in the near future.

Will it build local democracy?

A lot of people think Toronto needs a City Charter. If we’re being picky, and I am, it already has one in the City of Toronto Act, 2006. The sense is that we need that Act to have better protection, so that the provincial government can’t tear up parts of it on a whim during, say, a municipal election.

I agree that Toronto has a local democracy problem. I’m just not sure I agree where the heart of that problem lies.

When we focus on interference with our election, it seems like the issue is that the city must be able to defend itself against the province, which is assumed to be in some kind of power struggle with, or even hostile to, the city. Would a charter reduce hostility in that relationship through clarity of responsibilities? The history of the relationship between the federal government and the provinces suggests it would not.

Another way of thinking about it is to ask: in whose interest is it to have a charter? A big meeting was organized last June and something like 1200 people came out to talk about “empowering Toronto.” I participated in a roundtable about a year ago on the subject that drew a good 70 people. At both events, the vast majority of those who attended in support of the idea that Toronto needs a charter were white and middle-class, and from the old city of Toronto, York and East York. Racialized people, who constitute half this city, also believe in good governance. So why are comfortable, urban, white people the ones drawn to the charter solution?

Desmond Cole and others have explicitly asked us to pay attention to this. So I wonder: is it possible that a charter is a solution for the privileged?

I am part of a urban governance research team doing consultations with individuals and organizations who work in and with equity-deserving groups whose right to participate in the city is regularly compromised. We’ve found nobody is happy about what happened during the 2018 municipal election, but not everyone has the same concerns.

Many of the people we’ve spoken to feel even more removed from their councilors than ever, and are turning instead to community organizations, who are feeling the strain. When we ask about what local democracy should look like, people want better information and better access to city services. They want safer streets with less gun violence, zero deaths of pedestrians and cyclists, more and better parks, more and better libraries and public spaces, more community services, more housing, better transit. They want a city that consults and engages them but not in a tokenistic way.

That is what local democracy looks like to a lot of people in Toronto: public spaces and public services and public life, right where they live.

The quality of public life—of safety and housing and parks—matters in a democracy, because democracy is fundamentally a public activity. It is ordinary people gathering to discuss what matters to them, what needs changing, and what they can do about it. It is communities caring for each other. It is communities coming into meaningful existence in the first place.

I would like to see the power to determine the size of its own Council restored to the City of Toronto Act. But I’m not convinced that what is preventing Toronto from realizing its potential to be a great city for all is the provincial government. I don’t like what Queen’s Park is doing, but I’m not encouraged by City Hall either. The city charter debate frames the problem as a power struggle between the city and the province when, to my mind, it’s more of a competition between a conservative suburban elite and a liberal urban elite, leaving a lot of the city out of the discussion.

The Premier comes from Toronto, once served on Council and also ran for mayor. Is he doing anything more than using the powers at his disposal to shape the city as he wants it? Is he not of Toronto as much as anyone else here? Is his vision different from John Tory’s? What difference would it make if the latter had more power?

Local governance must be grounded in deep and inclusive local democracy. The City of Toronto is not, in practice, committed to that. Despite the efforts of a few councillors, Council as a whole is not committed to inclusive governance and certainly not to extensive public engagement (it voted at City Council in November not to even review its engagement practices). It’s not committed to doing something about the issues that would make this a more genuinely inclusive and just city, such as sharing stewardship with Indigenous people, ending carding, social housing, mitigating climate change. It is not really committed to local democracy, which is essential to all of the above.

Some city politicians talk about those things. But look at what we say, and what we do: Toronto often “commits” to things but they go unfunded at budget time.

I worry that wealthy white residents prioritize the idea of new powers for the city because it will solve their only real problem: it will put them in charge again. They don’t struggle to get their voice heard by their councillors or by the media. They don’t struggle for housing or services. When there are gaps in public services, they can afford to supplement them with private resources. Their mobility in the city is unquestioned.

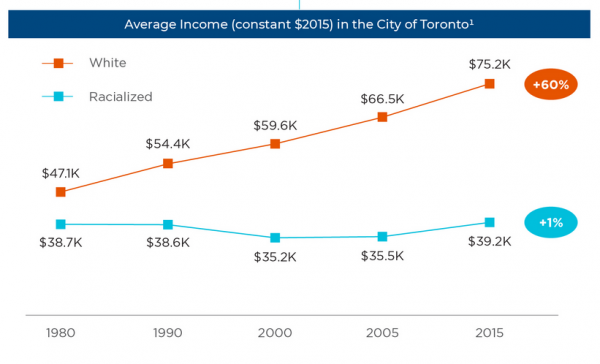

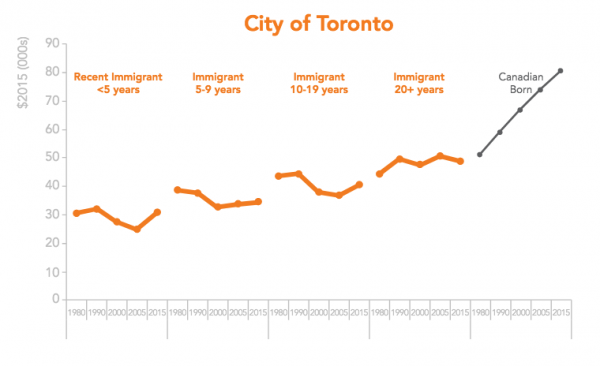

Meanwhile, racial and income polarization is growing. According to the latest Vital Signs report, middle- and high-income neighbourhoods in Toronto are overwhelmingly white, largely because racialized individuals have seen effectively no growth in their income over the last 35 years (1%), while white individuals’ incomes have growth 60%. The same research has also documented that those who weren’t born here make less than those who were, no matter how long they’ve been here.

A charter won’t do anything to improve local democracy if it only empowers a different elite.

A new charter with stronger powers and greater autonomy for the City of Toronto is a great long-term goal. But it will help us build a better city only if Toronto first establishes a thoroughly inclusive culture of community-level local democracy and public engagement. We don’t have that culture. We need it.

2 comments

I too attended the Charter meetings, and also came away with similar reaction. Then I discovered that organizing locally runs into political party machines that need to control those groups. Most community groups are managed by one political party or another. That’s how they prepare for elections. But I’m cynical.

I would still like to hear ideas on the best way to do it; I haven’t heard them here. Is there a model I’ve missed? Perhaps in the IMFG article?

So what is the answer to all of this? I keep hearing about the problems, especially the problems with proffered solutions, but no one seems to offer up ideas as to what we should be doing instead. There seem to be an awful lot of armchair quarterbacks in this city, no matter what the issue is. Though I care deeply about this city and have spent most of my life working for the public good, as one of the alleged “white elites,” I’m getting frustrated at hearing only about how I am part of the problem and, therefore, every solution I could put forward is tainted, but no one seems to be coming up with alternate solutions. I’m not naïve enough to think there are easy answers to complex problems, and if the Charter idea is too simple for the problems it is trying to solve, then we have to move on. I admit I don’t have the answers, so I ask the question of the writer and others: How do we avoid spending the next 3 decades in paralysis while we continue to articulate the problems and criticize every offered solution as inauthentic, and instead develop practical, implementable solutions that don’t have the whiff of elitism? It’s fine to say we have to fix local governance, but I don’t know what the practical implementation of that actually means when you have thousands of decisions a day that need to be made in a city this size, and when only a relative handful of people seem to be interested in being involved. I would be interested in hearing ideas on how the city could achieve meaningful consultation/involvement with its marginalized/racialized people. Perhaps a follow-up article?