The future arrived in Toronto in 1948, but it was hidden away from view, in a 19th century transit garage on Sherbourne St.

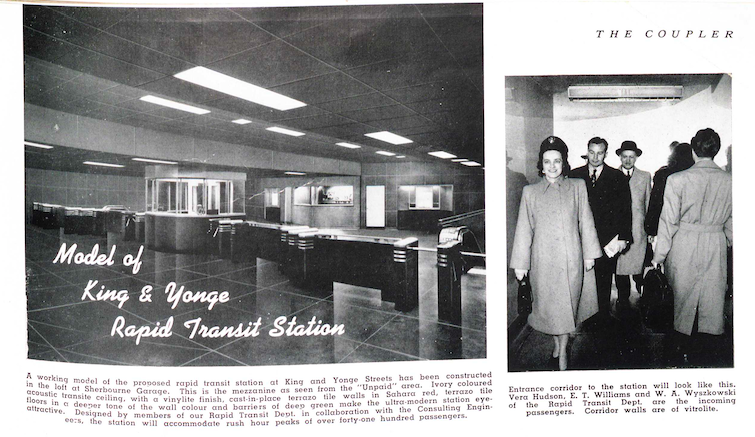

Six years before the long-dreamed of Yonge subway system finally opened, respected local architectural firm John B. Parkin Associates built a full-sized mock-up of a station inside the TTC’s vehicle facility, complete with a ticket booth, turnstiles, public phones, escalators and a newsstand. Snappily-dressed TTC employees walked through it to try out its functionality (to help envision the planned space, mirrored walls ‘doubled’ the size).

A “guinea pig station” never seen by the public, this glossy simulacrum of a speedy future stood in shiny contrast to the still-largely-Victorian temperament and style of the pinched and provincial city. At the center of the mock-up was a prototype glass ‘collector’s booth’, later to be perfected into a penny-wise panopticon, almost sci-fi in its presence, like the control booth for a spaceship (or, at least, a 1950s spaceship…).

As the TTC prepares this month to close the last of its subway booths in the final transition to Presto card gates, we should remember that the booths represented part of what might have been the first personal experience most Torontonians had of truly modern design on a large scale. The TTC subway, following designs created by Chief Architect Arthur G. Keith, and Consulting Architects John B. Parkin and A.S. Mathers, arrived to acclaim and wonder in 1954.

Much has been written since about the stark aesthetic of the original 12-stop Yonge line — “the world’s longest bathroom” was among the epithets. But even as that look (and the ‘Toronto Subway’ typeface) has gathered increasing respect and fondness from new generations of urban design fans, the sheer wear and tear of decades of use, a disregard by the TTC for its own design consistency, and a hodgepodge of repairs and upgrades, has meant that the classic look is harder to see and appreciate. With the demise of the booths, and their literal and figurative fading into the walls of the stations, we should at least pause (if not shed a tear) to reflect on their purpose and meaning in the transit life of the city.

As plans unfolded in the early 1950s, the TTC’s in-house magazine The Coupler referred to the subway stations “as clean-cut contemporary buildings”, and a contemporary newsreel praised them as “ultra-automatic”. Neither gritty and industrial-ish like the dank New York subway, or ideologically elaborate, like Moscow’s chandelier-adorned stations, the TTC’s designs also reflected the cautious attitude of a bureaucracy about to plunge into the creation of large public spaces that might breed misbehaviour. “Subway stations will be finished in public-proof materials to thwart those who find pleasure in scribbling on public buildings. Many juveniles and adults with juvenile minds make a habit of abusing public buildings”, declared TTC chief engineer W. H. Paterson in 1952.

In his 2012 dissertation, Searching For A Better Way: Subway Life And Metropolitan Growth In Toronto, 1942-1978, Jay Young wrote that public acceptance of the subway wasn’t a sure thing. “Convincing Torontonians to use rapid transit presented its own challenges. The TTC needed to show that the subway would be safe and enjoyable, or at least tolerable. By the 1940s, many people perceived subways as technologically backward, since systems built during the turn of the century began to show their age. As they thought about subways, some Torontonians were apprehensive about the underground.” What better way to allay those fears than through the use of bright, washable stations, staffed by crisply uniformed collectors sealed inside hygienic glass booths?

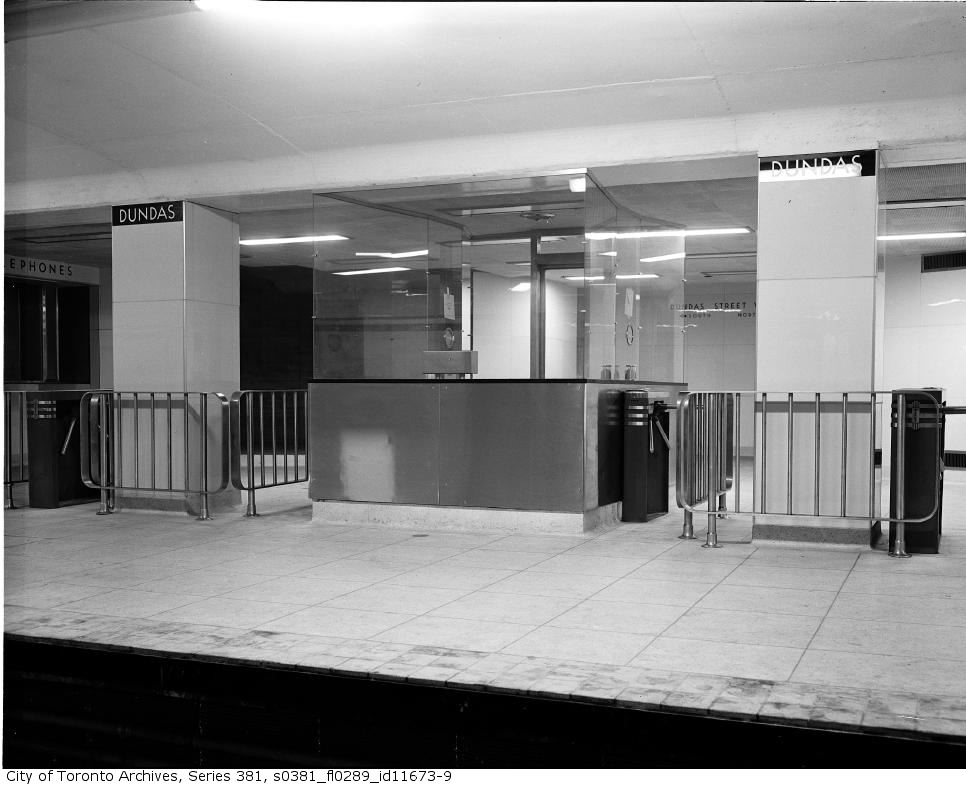

Photos of the stations taken just prior to the opening reveal an almost film noir look: moody, atmospheric, foreboding, and yes, sexy. Empty, and centred by the other-worldly glass booths, they resonate with us because they evoke a system many secretly wish for: one devoid of other passengers.

By 1949, the digging up of Yonge St. had begun, and by 1953 (think of the speed of construction!) the subway was close enough to completion to allow for advance tours for VIPs, including “film stars and other celebrities from every field of endeavour…from all over the world.”

Indeed, the Hollywood feel continued when several months prior to the opening, TTC staff again stood-in as ‘real passengers’ to test the now-functioning subway, this time under the klieg lights of a newsreel crew, passing a still-glassless booth to hand over their transfers to a uniformed collector, dressed like a military adjutant.

That glamour is long gone, and it’s likely few of us will miss the booths themselves, especially when one has spent a seeming lifetime, soggy paper transfer in hand, lining up behind someone buying tickets or tokens. Most booths have either been altered or replaced over the years, no longer reflecting the original clean design. With their imminent closure, or adaptation for other uses, the TTC has actually been camouflaging some of them with mock-tile material covering the glass, as if to make them disappear into the background walls. Is this the opposite of ‘facadism’?

The recent controversy over ‘fare evasion’ also reveals the weakness of the booth arrangement as a fare enforcement tool. I know: I spent three summers in the mid-1970s working as a collector, and have been struck since by how little the interiors have changed since then. Design icons of the 1950s, the booths were trapped in a cumbersome phase of the history of customer interaction, one long abandoned by other transit systems.

The booths were doomed by the TTC’s recent Station Transformation Plan, which, because of the implementation of Presto, determined that the subway “will no longer require Station Collectors to manage funds and fare media. The visible presence of collectors and customer service representatives deter passengers from evading payment.”

Booths were stupendously inefficient for security (the collector was never supposed to leave the booth to chase a fare evader, though we did have a turnstile locking button at our knee), communications (they presented a formidable audio barrier, requiring the use of hand signals/interpretive dance moves by a passenger to indicate to the collector that one wished to go through the turnstile to ask a question) and public information (badly-designed fare notices or hand-written service interruption bulletins were often goofily taped on the glass).

And if a collector needed to use the washroom, he/she couldn’t simply abandon their post, but had to wait hours for the ‘pee man’ to arrive, a fellow collector who merely travelled from station to station for this solemn, human purpose.

Unbeknownst to the public, we summer student collectors gossiped mercilessly, from within our ‘cones of silence’, about the passengers rushing by. The TTC was in my blood (thanks to nepotism, as my dad, Danny, was then a Yonge line emergency mechanic, the one who showed up to fix a train when the loudspeaker blared ’99, please call Control’), and I saw through those glass walls a pretty complete and fascinating cross-section of humanity. For one especially uncomfortable summer, the public took a curious interest in me, as I crewed the booth at St. Clair West station, one with no back wall, just another sheet of clear glass (long since painted over), allowing everyone to peer in at me all night, aquarium-style.

While the booth afforded me the pleasure of observing people, that’s something the system only begrudgingly offers its passengers. With few seats, and no real retail or food service, the subway is seen merely as a funnel to move people quickly through, despite the fact that it is, after all, the city’s largest public space.

It’s unlikely that the TTC will demolish all of the now-obsolete booths, especially as many have already been gathering dust for years, like the lonely outposts at secondary exits like Ossington station’s Delaware Ave. doors, or Lawrence station’s Ranleigh Ave. stairs. There they’ve sat, frumpy and unloved, and evocative of a time when a person like me could have a good, temporary union job reading pulp novels while occasionally glancing up at someone dropping a paper ticket in a farebox.

Why not open them up for those who want to watch the world go by (assuming anyone would want to self-isolate anymore …), like I was able to do? It would honour and preserve a tiny bit of Toronto design history, while allowing the creatively and valuably observant – say, painters, anthropologists, choreographers, comedians, writers, or architects!! — to use the booths as observation stations to chronicle and learn about the harried lives of their fellow citizens, injecting a sense of public purpose into an otherwise unused space.

The first booth I would suggest for this purpose is at Spadina station’s northern entrance, hidden inside the stately late-Victorian era Norman B. Gash house. Now weirdly blocked off by yellow metal safety barriers, the booth is a piece of 1950s design, inside a 1970s station, inside a 19th century house. If that doesn’t evoke Toronto, I don’t know what does.

2 comments

Wonderful piece of local history that adds richness to a daily subway ride. Thanks for sharing.

good idea