Spacing is teaming up with Coach House Books and Jonny Dovercourt to bring you a few excerpts from the new book on Toronto’s music scene from 1957-2001, Any Night of the Week (2020).

August 13, 1967, was a record-breaking day for the Toronto Island Ferries. Thirty-five thousand people made the journey across the inner harbour to attend the final day of a brand-new festival called Caribana. Nine months in planning, the week-long festival, modelled on Trinidad and Tobago’s Carnival, was Toronto’s growing Caribbean community’s contribution to Canada’s centennial celebrations. Montreal might have had the futuristic marvels of Expo 67, but we had a real party: calypso steel bands, sunshine, dancing, spicy food, colourful costumes, and, of course, a parade. It was a success beyond all expectations, and Caribana ’67 started an annual tradition that has defined the August long weekend in Toronto ever since.

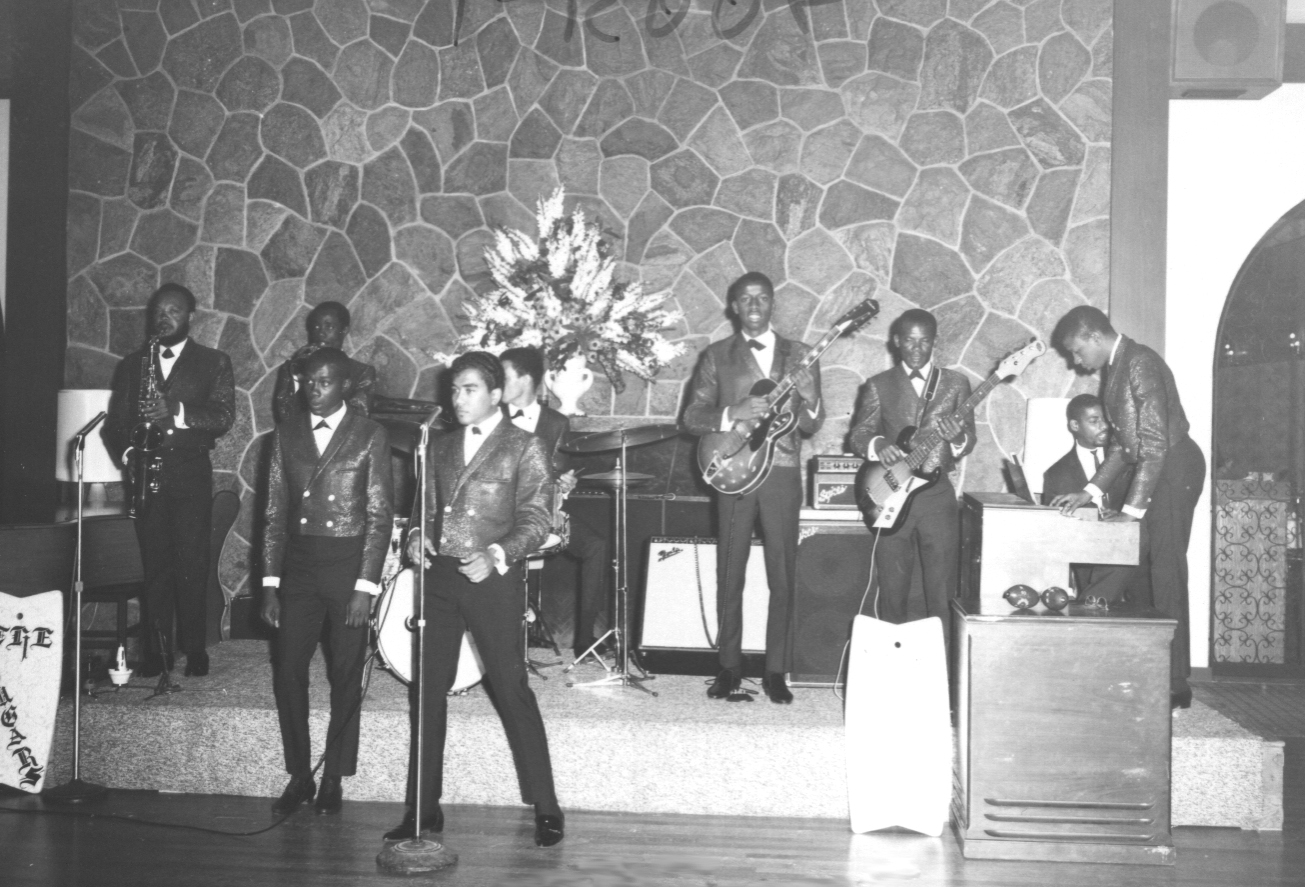

Live music at the first Caribana included Trinidadian calypso titans Lord Kitchener and the Mighty Sparrow, as well as a local band, the Cougars, fronted by Jay Douglas, who had moved to Toronto from Montego Bay, Jamaica, in ’63. They were one of several bands with members who’d been ‘drafted’ to come play in Toronto’s proliferating Jamaican clubs. Though at first these groups played Black American–style r&b to appeal to the expectations of Toronto audiences, they started to slip in some of the new sounds emanating from the studios and sound systems of Jamaica.

Canada had become an attractive destination for many Jamaicans fleeing political violence and economic uncertainty. Racist immigration policies started to become a thing of the past in the mid-fifties, at first to allow more Caribbean women to come to Canada as domestic workers. The 1962 Immigration Act, which focused on skills and education over race, helped liberalize entry, as did the point system, adopted in ’67. Prime minister Pierre Trudeau’s policy of official multiculturalism made the country look progressive and welcoming. People steered clear of the U.S. to avoid the draft. And there was work here, especially for musicians.

Karl Mullings was one of the organizers of Caribana ’67 and the booker of the WIF (West Indies Federation Club) at Brunswick and College. He was also a talent scout and manager who coaxed Jamaican musicians to make the flight north to Toronto. The Cougars were the WIF house band, while the Sheiks held it steady at Club Jamaica on Yonge Street.

Reggae, ska, and rocksteady were almost completely unfamiliar to white Canadian audiences. Little did Torontonians know they were in the presence of greatness: this exodus included some of the real innovators of the Jamaican sound.

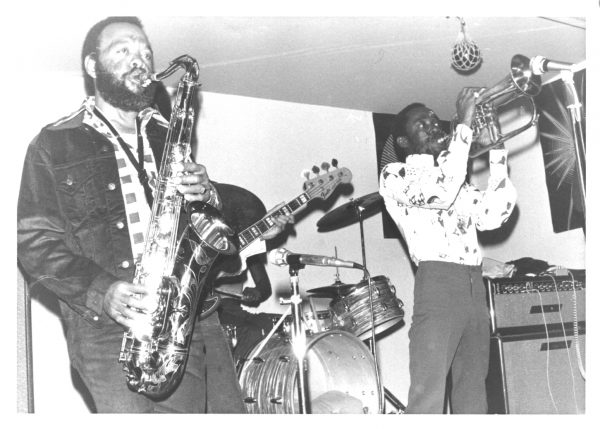

Jackie Mittoo was a musical genius, an astonishingly talented keyboardist and organist who had been a member of the Skatalites and the musical director at groundbreaking Studio One, the label/studio considered the ‘Motown of Jamaica.’ In 1969, he moved to Toronto. Despite his accomplishments in his native land, he worked some pretty thankless gigs. He was a solo entertainer at Fran’s restaurant in the early seventies, performing seven hours a day (!) all by himself. Later on, he moved over to Dr. Livingstone’s lounge at the Bristol Place Hotel, out by the airport. But he also got to open for Barry White at Massey Hall.

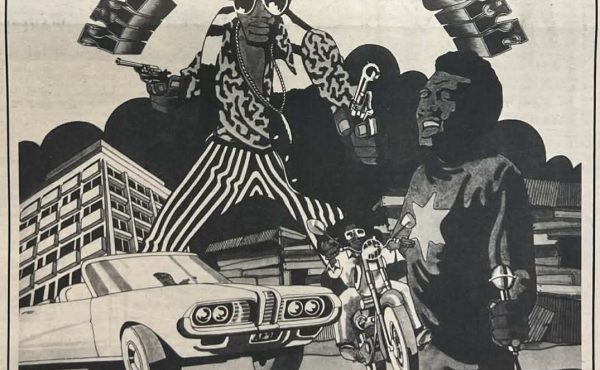

Another talented Jamaican musician didn’t have such a happy experience. Wayne McGhie was a singer/guitarist and, unlike many of his contemporaries, also a songwriter. In 1969, with the help of many of his Jamaican friends, he recorded an incredible album of stirring soul music that may be Canada’s finest contribution to the genre. Wayne McGhie & The Sounds of Joy was released the following year by Scarborough-based Birchmount records, but it was poorly promoted and didn’t make much impact on its release. To make matters worse, a warehouse fire destroyed all of the remaining copies.

Beset by mental health challenges, McGhie dropped out of music and out of sight, ultimately cared for by his sister. Meanwhile, Sounds of Joy became coveted by crate-diggers and hip-hop artists. In 2004, it was reissued by Seattle record label Light in the Attic as part of a series called ‘Jamaica to Toronto.’ In 2006, the series made waves with the titular compilation, Jamaica to Toronto: Soul, Funk & Reggae 1967–74.

Reggae music in Toronto was crucially DIY, driven by the passion of its creators and fans, who had to build much of the industry infrastructure themselves. By the early eighties, Jamaican-Canadian music was one of the city’s most important forms of musical expression, and reggae’s influence on everything from post-punk to hip-hop can’t be overstated. And it began in just a few clubs, booked by Jamaican musicians, who booked Jamaican musicians.

In 1974, Jamaican-Canadian music would get its first studio, the first Black-owned studio in the country. Reggae fan Jerry Brown moved to Toronto in 1968 and got a job in an auto body shop. He bought a house out near the airport, amidst the sterile sprawl of Mississauga. And he built a studio in the basement. His wife suggested the name Summer Sounds.

A community of musicians developed around Summer. People liked the vibe, that you could smoke weed inside, that Brown wasn’t afraid to push his gear into the red to get that big bass sound. Jackie Mittoo became Summer’s unofficial musical director, and a house band developed, named Earth, Roots and Water. Like Studio One, it became a label as well. The first Summer records release was a roots-reggae single by Johnny Osbourne in 1974. Brown sold it by taking it around to the several Jamaican-owned record shops that had begun to crop up on Bathurst and Eglinton West, a district becoming known as Little Jamaica.

But people weren’t that interested in Canadian-made reggae. To get the records to sell, he had to add a sticker that said, ‘Made in Jamaica.’

Jonny Dovercourt is a writer, musician, and concert presenter based in Toronto. He is a co-founder and the Artistic Director of the Wavelength Music Series. Check out his @spotify playlist here.

3 comments

I would love it if someone could provide me with information about “Truths & Rights” from the early 80s. I remember a live recording on CFNY where they played a tune “The Show Must Go On” but I can find anything about it or anything else.

Thanks!

Very good informative historical data. Significant to me personally. Traveled with my mother, “Miss Lou“ who came to take part in the initial parade & then to visit Expo 67 in Montreal. Memories by the Score. (Song). Stay Safe Walk Good.

Hi Steven, thank you for asking about Truths & Rights! This is Jonny, author of Any Night of the Week. There is a chapter about the band in my book which might interest you. Nicholas Jennings also recently wrote this very informative post about the band: https://www.nicholasjennings.com/truths-rights-the-great-lost-album

Nicholas’s blog post coincides with the happy occasion of Truths & Rights’ “lost album” Time for Us to Unite recently getting (re)issued. It is now available on Spotify and iTunes for your listening pleasure. Songs like “Acid Rain” and “Metro’s No. 1 Problem” sound fresh and vital today!

And Fabian, thank you very much for your kind words. I am glad to hear you and your mother were there to witness the first Caribana and Expo 67.