My experience in community bike spaces, and later in cycling advocacy spaces, has been profoundly impactful and transformative. I have become acquainted with how mainstream cycling advocates in North America engage in a discourse that works towards changing dominant culture – specifically car culture – as a central objective.

The call for car-free streets or open streets can illustrate an imagination that conceptualizes public space in a way that is, in part, transformative.

Riding car-free open streets events such as CicLAvia and Open Streets Bloor have been cherished experiences for me. Yet I also know intuitively that streets that are free of cars, or that are designed so that cars cannot easily cause harm or worse, do not inherently keep streets safe. Infrastructure alone will not create “safe” or “complete” streets.

Defining “Safety”

The focus on safety on streets only as it relates to vehicular dangers alone betrays who more readily accesses space in cycling advocacy, whose voices are amplified, and whose safety streets are continually produced to preserve.

In a webinar with members of the Untokening collective, Urban Studies professor Dr. Do Lee asked the question “who has the power to determine safety?” Moreover, he aptly asked “who do we design safety for and who do we design safety from?”

Personal Experiences Negotiating “Safety”

I have heard discussions in the cycling community about how being on a bike is an experience that made some feel a new sense of vulnerability. Since even before I became an avid cyclist, by virtue of being a Black woman I have constantly orbited a lack of safety. The complexities of how marginalized people experience a lack of safety are inadequately grappled with. The disproportionate exposure to a lack of safety that marginalized people face broadly fails to be discussed or even acknowledged, whether in cycling communities or our society more broadly.

Black people are not afforded safety, even in childhood, a time often recognized as a place of innocence and exploration. Many of us at an early age are informed of the different ways in which we will be seen as a threat. Our caregivers equip us with this knowledge to try their best to keep us safe, while ultimately recognizing that the world outside undermines our safety at every turn – and then casts us as the threat, or as being suspicious, or out of place – and the list goes on. This experience informs how we navigate public space and conceive of safety.

My feelings of lacking safety have been heightened by my experience on a bike; nonetheless, they are ever-present on and off my bike.

Narrow Focus of Current Advocacy

Cycling advocacy has largely shifted towards coalescing around broader road-safety initiatives for pedestrians and cyclists, namely initiatives like Vision Zero. Mainstream cycling advocates and active transportation advocates in North America over the past few years have embraced Vision Zero as a solution for safe streets. The Swedish-born safety plan operates on the premise that it can never be “ethical” or “acceptable” that people are killed or seriously injured while moving about their communities. That fatalities and serious injuries incurred while accessing the streetscape can be eliminated by engineering and design.

Cycling advocacy, as well as urbanism more broadly, often touts European-born solutions to improve cities and cycling in North America. However, in doing so it neglects different and specific contexts and histories, including those surrounding race in North America. In Bicycle Justice and Urban Transformation: Biking for all? Aaron Golub, Melody L. Hoffmann, Adonia E. Lugo and Gerardo F. Sandoval make the powerful assertion that “the possibility that Northern Europe’s prized public spaces and transportation investments reflect a much broader social and political commitment to equality and dignity does not come up in the pitch for U.S. bike infrastructure.”

The uninterrupted continuity of street-based violence that Black people experience illustrates how we are continually both invisible and hyper-visible. This experience extends to Indigenous people and others, particularly those who are at the intersections of marginalized identities.

What is the utility of Vision Zero if it does not orient itself around justice?

The Necessity of Contesting Enforcement

Vision Zero, in the many North American cities where it has been adopted, has largely failed to keep people safe; this failure is illustrative of systemic issues and the dominance of our car-centric culture.

However, the failure of Vision Zero that we have witnessed across Turtle Island has been coupled with a further emphasis on using traffic enforcement as a solution for pedestrian and cyclist fatalities.

In Toronto, the police budget continues to increase, while the enforcement of traffic-related offences decreases. Many cycling advocates nonetheless demand that yet more resources be allocated to the police to enforce traffic-related concerns as a component of Vision Zero and to ensure public safety.

Calls for increased enforcement are often coupled with a lack of consideration for or consultation with those particularly susceptible to surveillance, violence and state terror, which falls along class and race lines.

The cycling community in US and Canada predominately caters to the interests of white middle-class people – particularly men – who ride bikes and enjoy a wider sphere of social influence. These cyclists with more social capital call on the state to protect them and enact their will – not just when it comes to traffic safety, but more broadly – with the intuitive knowledge that the state has and will continue to protect them.

Increased enforcement inevitably adversely impacts marginalized communities. Additionally, penalties and sentencing always impact Black and Indigenous people more adversely. Encouraging increased ticketing in communities that are notably marginalized along the lines of race and class – because those are where the highest rates of vehicular death and injury are – plays a significant role in destroying trust and exacerbating inequalities.

I am not talking about trust in the police since for many BIPOC including myself that has long been broken, but trust in cycling organizations and other active transportation enthusiasts that insist that they want to get everyone moving through their communities safely.

In many documented police killings of Black people, the encounter began after the victim was pulled over for the purpose of traffic enforcement. On September 5, 2019, Byron Williams a Black man on a bike in Los Vegas, was killed at the hands of the Los Vegas police after being arrested for riding his bike without a safety light. Undoubtedly many in Canada and the US experience similar violence that goes unnamed, given that Williams’ killing itself received little press coverage – or ostensible attention from local cycling organizations. In name, these traffic enforcement regulations act to promote safety, but when Black people are killed during the process of enforcing “safety”, and Black people are unduly targeted and surveilled in the name of preventing crime in service of preserving a particular conception of safety, whose safety is being preserved?

I recognize the ways that the safety of marginalized communities and particularly Black and Indigenous people is disregarded at every turn and that, in turn, we are often provided policing and enforcement as the only option to keep us safe. The options for “safety” presented provide a false choice – because we do not have the power to determine safety or to be imagined within its folds.

The question of who our conceptions of safety serves makes me recall discussions surrounding safety in the aftermath of the gentrification of Regent Park. This neighbourhood in downtown Toronto, has been stigmatized for many years, but the stigmatization abated following the city-led gentrification of the community. Prior to its gentrification, Regent Park’s population was majority people of colour and had a sizable Black population. Long-time residents and activists challenged the way that, following the city-sponsored gentrification of their community, there was suddenly an extensive dialogue about safety in the community. Many asserted that this discourse was not focused on the wellbeing of long-time residents, those who had, long before, had concerns about safety. Long-time residents, particularly mothers in the community, have for many years strived to make their communities safer. Those invested in the wellbeing of their community, those who had buried young loved ones in Regent Park, have worked for years to make their community safer and have been ignored. Instead the new focus on safety centred on the safety of the new wealthier, white residents. Our understandings of public safety are informed by racism, which influences the tools we use to facilitate ‘safety,’ and this understanding inevitably manifests itself on our streetscape.

Many are leading with enforcement to facilitate safe streets because we have already failed vulnerable street users. Our imagination of solutions to street-based safety and how people experience a lack of safety is stunted.

Atoning for and Reimagining our Streets

Furthermore, when we look at things like speeding as an individualized occurrence and a personal failure, we disregard the way in which the built environment has been proven to play a role in facilitating unsafe conditions that encourage speeding.

Internationally renowned placemaker and author Jay Pitter has said that “urban design is not neutral, it either perpetuates or reduces social inequities.” Marginalized communities that live in neighbourhoods that confront them with lack of safety in a myriad of ways – which is a by-product of state neglect, as well as social and political choices – are provided streets that expose them to more harm. We are provided these streets in a manner that fails to atone or acknowledge past and ongoing harm, and that continues to perpetuate this failure and under-resource our communities.

Dr. Destiny Thomas, a community organizer and esteemed anthropologist planner in her brilliant piece, ‘Safe Streets’ Are Not Safe for Black Lives she articulates the risk of re-designing streets without the input of Black people and the ways in which racism and other forms of systemic oppression sets the stage for our current streetscape. She warns against the development of street redesigns in marginalized communities without substantive engagement with Black residents, which risks adversely affecting the communities these streets may claim to serve. I would encourage cycling advocates to embrace visions like Dr. Thomas’, which she lays out in her calls to action. Dr. Thomas outlines seven calls to action, articulating visions that in part call for a reimagining of the facilitation of safety, including the following:

Public works and transportation agencies should produce and publish a concrete plan for divestment from police agencies. This includes both fiscal and values-based components: Enforcement should be replaced with accessibility and accountability, and funds to police should be redistributed to community-based organizations, direct service providers and behavioral health specialists that are equipped to uphold dignity and care for everyone within the built environment.

There is failure to address the conditions that create harm, which is meant to be Vision Zero’s central premise. Furthermore, there is a notable failure to acknowledge and engage the needs of marginalized communities, who in name are claimed to have been served. Many residents of over-policed communities and mobility equity experts have raised these concerns for years, notably Tamika Butler, who has brought these conversations surrounding Vision Zero into the fore. Will we finally listen to them?

We suffer from a failure to address the harm that systemic racism inflicts on our society and streetscape. We have also failed to substantively address gender-based fears in navigating public space, ableism, and more.

It must be recognized that bikes are not neutral forces of good. I do not believe that bikes alone can change the world – my lived experience and the immense harm that transportation planning has and continues to facilitate tells me otherwise. I believe bikes can be tools for good – but that depends on how we use them. Those dominant in cycling spaces can uphold a dominant culture that threatens to be a continuation of how transportation planning has been weaponized against lower-income racialized communities, or they can open up their movement and expand their vision of safe streets.

Let us engage in a transformative vision that cycling advocates in some ways conceptualize when they call for “open” streets.

We need to engage and invest in marginalized communities in transformative ways. Communities that have been historically neglected as a result of systemic inequality – communities that have been criminalized, neglected, and ignored.

To return to Dr. Lee’s question, who will we continue to define safety for? And who will we continue to define safety from? Only in recognizing these questions and taking action can we begin to work towards truly safe streets.

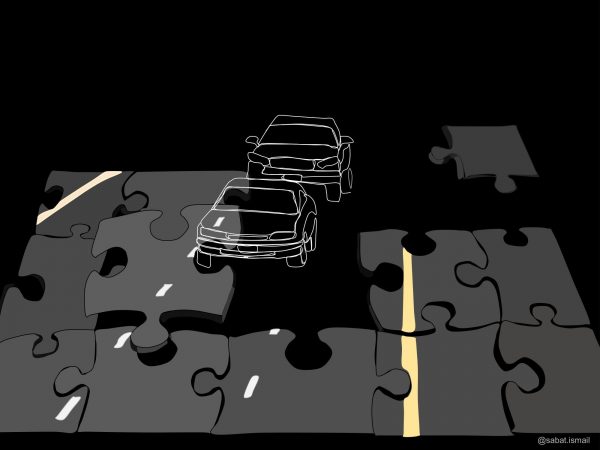

Image by Sabat Ismail

3 comments

Thanks for this thought-provoking article, Ms Ismail. It’s an issue I hadn’t considered before.

Thank you for bringing a perspective to the safe streets discussion that is rarely considered. And the links are helpful to further explore where we need to go to bring street safety to all our communities.

I found this articulate article to be an interesting and educational read Sabat. Surprising about the city-sponsored gentrification of Regent Park; how only after the gentrification, did safety measures are put in place. I recognize also that people who are most vulnerable and are also using the road needs to be consulted with before road users safety in urban planning amends.