By Saquib Ahsan, Ruth Belay, Abigail Moriah, and Gervais Nash

The deaths of Regis Korchinski-Paquet, Abdirahman Abdi, Ejaz Choudry, and countless other tragedies have occurred in urban centres — the sites of contention, struggle, and symbolic diversity. Urban planning is the relatively silent field that shapes both our built environment and social/economic infrastructure. Created to regulate land development, planning not only enforces but also builds upon settler-colonial land management practices. As a result, the field struggles to connect and engage with marginalized communities.

Critiques of contemporary urban planning have urged the profession to critically reflect on systemic issues affecting both the profession and dominant planning approaches. In a profession charged with planning for the coming generations of people living in urban and rural settings, we must ask why the professionals employed to carry out this work do not reflect the diversity of the Canadian communities they plan.

In the absence of this diversity, how can planning understand the contexts of Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (POC) communities, as well as address the issues these communities face: displacement, gentrification, socio-economic polarization, food insecurity, homelessness and gun and police violence.

In 2019, a team of University of Toronto masters in planning students sought to answer the question within the scope of the Greater Toronto region. They posed this research question: what experiences did Black, Indigenous, and other persons of colour have in navigating their planning education and work life?

To reach an answer, the team conducted a survey and individual interviews, and presented their findings to the Mentorship Program for Indigenous and Planners of Colour (MIIPOC), based in Toronto.

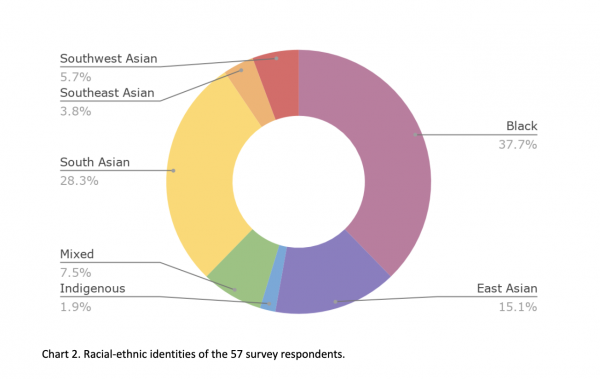

Early in the research process, it became clear this was a relatively new area of exploration within the Canadian context. To compensate for the gap in Canadian literature, the research team drew from relatively similar examples in the American context. Through a two-prong approach, the research team designed a comprehensive survey alongside qualitative interviews. In only four weeks, the survey received significant interest, with more than 57 responses and 30 requests for interviews. Both survey responses and interviews explored the experiences of BIPOC planners and planning students in academic institutions, planning networks, employment opportunities and career progression.

From the analysis of data, four main themes emerged: career, network, support, and retention. The research team found considerable overlap in identifying systemic barriers and potential support systems.

In the Workplace (Career)

Participants described issues from the beginning of their professional careers, from being excluded from job opportunities to feeling like they didn’t belong in those spaces if hired. These experiences contributed to or caused mental and emotional distress. In addition to these barriers, BIPOC planners found it difficult to find allies in the workplace. As a result, BIPOC planners often left jobs, or even the planning profession, to seek more fruitful opportunities which allow for career advancement.

Professional Networks

Interviewees reported that on account of their race or culture, they did not have the same access to professional networks. Among the barriers mentioned: the location of events. Many are held primarily in the downtown core, an area that continues to become less diverse, and often in bars, which exclude those who abstain from alcohol consumption. Additionally, these environments (or networks) promoted a “boys’ club” atmosphere. BIPOC planners need networks that are accessible, supportive, accommodating and understanding of the unique barriers they experience.

Support

An often undervalued component of a network is the way in which it supports its members, enabling them to develop both personally and professionally. Many survey respondents expressed a sense of discomfort and intimidation when attending networking events, mostly because of the lack of diversity. In the academic environment, BIPOC faculty representation falls short across the board. As a result, in places where an emerging professionals might meet a mentor, BIPOC planners are put at a significant disadvantage.

Retention

BIPOC planners want to be part of a profession and workplaces that value their whole selves and interests, and foster their excellence. As it stands, the majority of participants expressed a lack of opportunities to discuss racial injustice in planning. When working within this context, they experienced an internal conflict of working within this system while simultaneously being pigeon-holed into acting as representatives for marginalized communities. By being assigned to work on specifically equity-seeking files, BIPOC planners were excluded from gaining the wider experience needed to move into senior roles. Some felt it necessary to be an advocate, while others were burdened by the expectation.

Key Takeaways: Pillars of Mentorship

We suggest that these four pillars of mentorship (career, network, retention, support) are rooted in the need to address existing barriers and develop a strong community of support. Through establishing a community of support, higher education institutions, firms, professional networks and public sector employers can support BIPOC planners and students. A community of support for BIPOC planners has the potential to not only diversify the profession, but also promote social justice and equity in planning practice more broadly.

Each of us has a role to play as members of the planning profession, both BIPOC and non-BIPOC. This project is part of the larger narrative and we need to engage with the pillars of mentorship in different areas.

What are some of the ways to create a supportive environment for BIPOC planners and students to excel?

Recruitment: Firms ought to to identify new recruitment strategies that include mentorship and support for career advancement. There needs to be a critical reflection on workplace cultures and planning practices to ensure they are rooted in equity and social inclusion.

Academia: It is essential for planning faculty to review curricula and teaching staff to ensure they are not instructing students within a pre-existing framework of discriminatory practices. Academia can further build on this study to conduct research focused on understanding BIPOC planners’ experiences in the academic environment and profession, and also engage more BIPOC planning professionals, or those working on issues intersecting closely with planning, as instructors or guest lecturers and research leads. Planning programs can also diversify planning theory/approaches through the inclusion of courses focusing on intersectionality, reconciliation and anti-racism.

Professional associations: Planning networks, such as the Ontario Professional Planner Institute, Canadian Institute of Planners and Urban Land Institute, can collaborate with and support BIPOC planners. Additionally, firms, institutions, and the public sector must work collaboratively with BIPOC-focused networks (i.e.like MIPOC), to help BIPOC planners to develop strong professional networks and advance in their careers.

Public sector: Government divisions responsible for planning and related fields, such as housing, environment and land development, could potentially have significant impact if they prioritized hiring and subsequently supporting BIPOC planners as they build their careers. Given their size and work, government departments should do more to prioritize internship opportunities for BIPOC students, giving them valuable work experiences early in their careers that can be leveraged to competitively prepare them for work in other sectors.

Finally, we all need to examine and dismantle the racist and inequitable perspectives and practices we may hold as individuals. We need to listen to, amplify, and support Black, Indigenous and Persons of Colour in creating excellent community and city-building outcomes. The entire land development industry will benefit from a wealth of diverse perspectives, beyond the traditional land-use planning expertise. Society as a whole will benefit from more equitable cities.

photo by Sebastiaan ter Burg (cc)

Saquib Ahsan, co-founder of MIIPOC, is a first generation Bengali-Canadian (born in Bangladesh, raised in Regent Park), who will be starting his masters in Environmental and Urban Change at York University this fall.

Ruth Belay (MScPl, 2020) is an Ethiopian-Canadian urban planner actively engaged in Afro-centric approaches to planning and policy.

Abigail Moriah, RPP, an Afro-Caribbean Canadian who works in housing development, is co-founder of MIIPOC and founder of the Black Planning Project at @blackplanningproject.

Gervais Nash (BURPI, 2020) is an Afro-Caribbean and Metis Canadian and co-founder of MIIPOC. Follow MIIPOC on twitter at @MIIPOCca, LinkedIn or IG, @miipoc