Does your Blue Bin runneth over?

On my morning dog walks, I’ve noticed in the past several months that a growing number of blue bins hauled to the curb are not just over-filled, but come accompanied by a stack of flattened cardboard boxes, evidence, should you need any more, that e-commerce is the pandemic’s single biggest business story.

The proliferation of grinning shipping packages isn’t just a house-neighbourhood phenomenon. Anecdotally, I’ve heard numerous stories now of apartment or condo lobbies that have turned into overcrowded parcel depots.

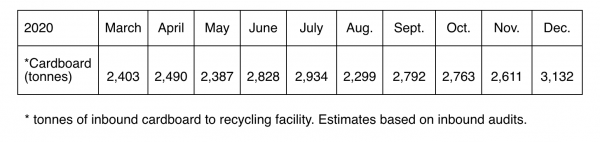

The City’s recycling data confirms these impressions.

Between March and July, cardboard in the municipal solid waste recycling stream rose by 22% by volume, to 2,934 tonnes in July. After a slow August — holidays! — the monthly figures again jumped, including a predictable spike in December. The fall average was in the 2,700-2,800 tonnes/month range.

Those amounts don’t include all the additional food packaging waste created because most people are eating at home most of the time, nor do they account for what private waste haulers pick up from apartment buildings.

According to a City spokesperson, excess recycling requires more collection time and can contribute to increased costs. (The 2021 budget recommends a one-time 1.5% waste management fee increase to make up for $3.3 million in lost revenue due to the pandemic; fees will increase 3% per year thereafter.)

Also, wholesale prices for corrugated cardboard, which the City sells, had been dropping for several years prior to the pandemic, but spiked last May and have settled out at a rate that is about twice what it was in January 2020.

This shift in our collective waste production habits raises, to my mind, a wider question: how do we go about calculating the carbon footprint of the pandemic and post-pandemic city?

Various short-hand answers surfaced early on: way less jet fuel, less car travel, and so on. We’re only using part of the city’s work-oriented built form, although all those mostly empty offices are still using energy. While car use, in the aggregate, is still well below what it was pre-pandemic, there’s plenty of anecdotal evidence to indicate that people are using their cars for trips they might previously have made on transit (although some of the transit users have shifted to bikes).

I’m guessing that travel patterns will gradually return to more typical levels once the vaccine roll-out gathers momentum, but I am much more doubtful that the dramatic shift to e-commerce that occurred during the pandemic will reverse itself.

The debate over the carbon footprint of e-commerce is not new. The giants of this space — Amazon, most notably — have advanced the mostly self-serving argument that e-commerce is easier on the environment. There’s some truth in the assertion that one delivery truck with a hundred parcels and an optimized route produces fewer emissions than a hundred separate return trips to the mall.

But Miguel Jaller, co-director of the Sustainable Freight Research Centre at the University of California, Davis, has found that when e-commerce firms offer rapid delivery options, like Amazon Prime, those savings go, well, up in the smoke.

There’s also the double and triple packaging issue, as well as the one-off problem. E-commerce is ridiculously easy so many consumers buy one thing at a time. Jaller argues, correctly, that aggregating your purchases into a single order leaves a lighter footprint, but that’s only possible if you’re buying stuff from one site.

E-commerce has been racking up double-digit growth for several years, of course, but the new reality is that we’re moving rapidly to a world in which many consumer products now arrive wearing multiple packages, including an overcoat that often bears no relationship to the size of the thing you bought, and includes more paper or foam or other kind of packing material.

Yes, we may be moving to a world with fewer single-use plastic bags, but the alternative doesn’t seem like an improvement. Cardboard recycles well, of course, but the fact that it can be re-used industrially shouldn’t be seen as an absolving factor in this kind of consumer trend. There’s simply no question that the volume of packaging waste is just rising relentlessly.

How all this plays out in terms of the province’s product stewardship policy is a kind of open question. To help pay for the blue bin program, Stewardship Ontario collects fees from registered “stewards” (i.e., packagers), and Amazon is on that list. Jennifer James, Stewardship Ontario’s spokesperson, declined to say how much Amazon contributes, but notes that the organization audits participating firms.

For 2020, according to a 2020 fee spreadsheet James supplied, Stewardship Ontario’s rates for corrugated cardboard ranged from about 11 to 14-cents per kilogram, generating total revenues of $13.3 million for the whole province, or about 10% of Stewardship Ontario’s total income.

Between 2021 and 2025, the province is shifting the whole system, so packagers will (theoretically) cover the entire cost of the municipal blue bin program. City officials have yet to figure out how that transition will work, but are expected to provide an update this spring. The transition plan pre-dates the pandemic, and it will be interesting to see how the shifts in consumer buying habits affect these moves.

Stepping back from the always confusing nuances of our recycling infrastructure, it will also be critical for city council and Torontonians, generally, to consider a broader but related question, which is how the pandemic — and post-pandemic conditions — will impact the City’s long-term climate plan, approved in 2017 and dubbed TransformTO.

The plan, which aims for net zero by 2050, focuses on buildings, transportation, and waste. The built form goals — tougher energy standards, more home retrofits — are likely unaffected by the pandemic. This assumption seems less true for the other elements of the strategy, which depend on wide-scale adoption of electric vehicles and a goal of 95% diversion from the municipal waste stream.

TransformTO is a 30-year-plan based on trajectories that have, in part, been scrambled by the pandemic. The latest update pre-dates the lockdown, and the City’s 2021 budget plan, which is being reviewed this week, doesn’t specifically break out expenditures relating to TransformTO.

What’s more, 2030 is a critical juncture in terms of global climate change. How long will it take for the city to climb back to the pre-pandemic transit ridership levels of about 530 million trips per year (for those keeping score, it took the TTC a decade to rebuild after the ridership plunge of the early 1990s)? And what happens to municipal solid waste in a world in which ecommerce becomes the default way in which most people shop for just about everything?

I certainly don’t have the answers, but these questions need to be addressed. As those now chronically overflowing blue bins suggest, the pandemic’s lingering impact on the city’s carbon footprint won’t end when COVID19 stops spreading.

photo by John Lorinc