On Indigenous People’s Day, June 21, Anishnawbe Health Toronto held its ground-breaking ceremony for the Indigenous Hub that will stand at Front and Cherry Street. The project is more than 20 years in the making, and will include an all-in-one location for Anishnawbe Health. The facility is scheduled to open next year.

The hub will provide the members of Toronto’s Indigenous community with a multitude of health services, including traditional and Western medicinal practices, all under one roof. Aside from the health centre, Miziwe Biik Training Institute will also have a new location there, along with condos, a rental building, a childcare and family centre, and a restaurant within a restored heritage building comprising the rest of the hub.

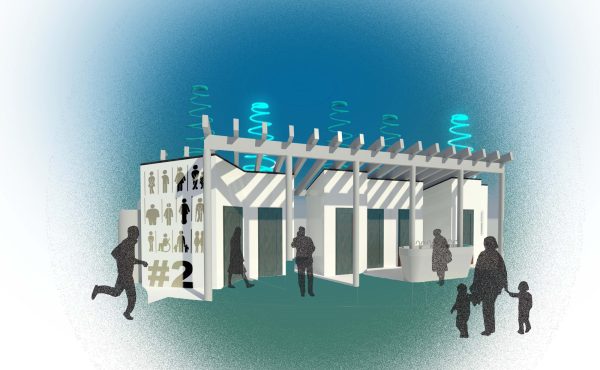

The design team includes BDP Quadrangle, Stantec and Two Row Architects. The development partners include Dream, Kilmer Group and Tricon Residential.

I was able to speak with Joe Hester, executive director of Anishnawbe Health. He first had the idea for this project years ago, and has seen it finally come to fruition. Hester originally envisioned a new, larger location to make healthcare more accessible for community members who were not always able to travel to AHT’s clinics across the city.

For a nominal fee, the organization had acquired a 2.4-acre lot in the West Donlands, on the site of the former PanAm/ParaPanAm Games athlete’s village. The project grew to include more than just Anishnawbe Health, and is envisioned as a gathering place. The organization conducted community engagement sessions to understand what the community wanted in the space.

I asked Hester more about the project’s evolution and how it will positively impact the Indigenous community.

MGC: I know that this project has been 20+ years in the making. What was the initial vision of the project and how did it evolve into what it is today?

JH: Initially, Anishnawbe Health were really faced with a space challenge in terms of the growing need for services, health services and programs by the community. And so, we embarked on a plan to look at acquiring a larger facility and acquiring land to build on. That was the initial dream, so to speak. We did that for a number of years trying to locate land and then finally, this opportunity came up where that piece of land [that] is located at the corner of Front Street in Cherry Street [became available]. So the health center project grew suddenly into [having] the potential to develop that property, and to do other things with it as well. So that’s kind of in a nutshell of how it grew from, you know, just wanting to build a larger Health Center, and now evolved into an Indigenous hub.

MGC: I know you hired Indigenous architecture company Two Row Architects to work on the project. Why was it important to work with an Indigenous architect company?

JH: I think what we communicated all along [to the developers was], first of all, we felt that the overall project could be a reconciliation project. [Secondly,] we also wanted to convey in an architectural sense who we are. We wanted to build a place to call home but it needed to reflect who we are as a people. And so the best way to translate that [was] into actual architectural design and what kind of materials are used. So we spoke to our consultants and said, “Look, you know, maybe you should engage an Indigenous architect to help with this.”

The other thing, I guess that’s important to us, and I’ve said this on numerous occasions, [that] you can walk in Toronto, and you’ll see many different cultures who have an established place. Like maybe Chinatown, maybe for the Greek community, certainly, the Italian community and that’s fine. But there’s no place where we can speak of, in terms of Indigenous peoples. And so we wanted to bring a sense of that in terms of moving beyond the placemaking of just renaming of streets or [erecting] statues, that kind of thing. We wanted to bring placemaking to a whole new place, a whole new [level]. Like we built on a city block [that’s] 2.4 acres in size, a place for Indigenous people.

MGC: You mentioned earlier that this is a reconciliation project. Can you elaborate on that? How is this new Indigenous hub working towards reconciliation in Toronto?

JH: Oftentimes when, in terms of our people and our community and the kinds of things we had to do in the past — like if we had to work with say the justice system, or the social service system, or the educational system — we brought our worldviews to those discussions, to adjust those institutions, so that they could better accommodate our people. And so universities began to, for instance, offer courses and programs of Indigenous Studies.

When you go to the kind of project that we were trying to finish here, it involves economics and it involves development. So if we talk about, let’s say, economics, we have kind of diverse viewpoints, worldviews, where in the non-Indigenous sector, it’s primarily profit making and that kind of thing. And that, first and foremost, has to happen. Well, we may not necessarily disagree with that in terms of Indigenous people, but we found that there are better ways, or at least different ways, of achieving that as well. So it’s kind of a reconciliation of different thoughts on development. And working together to reconcile differences and to be able to achieve something that will work, and hopefully, to some degree, accommodate both worldviews.

MGC: Why are Indigenous-led services like Anishnawbe Health important to have, not just in Toronto but in Canada?

JH: I think there’s a long way to go before our people feel comfortable within those [health care] environments. There’s a long history [of discrimination against Indigenous people in the health sector]. We’re not feeling comfortable, [there is] distrust and those [cases] are still happening to this day. So it’s important to have institutions of our own, where we can bring ourselves to it, in terms of our culture, our approaches and our understandings, so our people will feel safe, and see themselves reflected in terms of those kinds of services. They are still important, and very much so needed in our communities right across the country.

MGC: Can you talk a bit about how Anishnawbe Health has helped the Indigenous community during the COVID-19 pandemic?

JH: Early on, we started to realize, like everybody else, that this was serious. And what we know of in terms of our community, it’s not easy for our people, oftentimes, to access health resources where they feel safe and comfortable. So part of our strategy included mobile services, where we could go out to the community where we would conduct, in the early going, testing for COVID as well as providing primary health care services and other services that might be needed. That eventually evolved into providing vaccines as well.

We still do vaccinations from our mobile resources. We have two vehicles. But we also do clinics that are at one of our locations. So a combination of both has been really helpful for where the community can get vaccinated. And of course, we don’t claim that all our people will come through Anishnawbe Health, or any other service in the community in terms of vaccinations, because there’s too many to be able to do that. Our people are able to get vaccinated in other locations, which is great. But once we get past COVID, we see our mobile services continuing on and [offering] different other kinds of services. Maybe it’s dental, maybe it’s vision, maybe it’s diabetes — all kinds of other possibilities. And we’ll be pursuing those possibilities at some point in time once we get beyond COVID.

MGC: What else do you imagine for the city that can make it a more safe and welcoming place for Indigenous peoples?

JH: Well, I think, unfortunately, sometimes lessons have to be, for whatever reason, learned in a very difficult way. You know, the children spoke to all of us, in Canada. In the first instance, the 215 and then later, over 700. When that first happened, most of us thought that was only the tip of the iceberg and they’ll continue. I guess in a funny kind of way, it’s opened eyes, it’s opened hearts and minds. I think it has created a fertile environment where we can now reach out to each other, break down those barriers of the past, and gain new understanding and appreciation. Hopefully, [we can] overcome some of those barriers that we’ve had between us as peoples and can create a much more positive environment.

MGC: Finally, how did it feel finally putting in the shovel for the ground breaking ceremony, knowing that your vision was finally coming to life?

JH: Well, for me, personally, it was a major step. It’s very hard sometimes, too, because this project, I’ve been working on it for a long time. You see slow and incremental kind of changes. Sometimes it’s backwards steps and fighting all the way and then finally, you realize that you can put shovel in ground now and break the ground and start. The next step is getting the construction started. It’s not only a big relief; it’s also so much of that realization that all those efforts have been worth it.

photo courtesy of BDP Quadrangle

Mnawaate Gordon-Corbiere is Ojibwe and Cree from M’Chigeeng First Nation. She is a young historian with a focus on Indigenous history. Follow her on Twitter: @mnawaate.