Avenue Road is the enduring legacy of Sam Cass. Very enduring.

Cass was the traffic engineer hired by the new Metro Toronto government created in 1954 to federate the city of Toronto and 12 other local municipalities. His task was to create a network of roads that would bring people efficiently into the downtown core and take them back to their suburban homes at night. That was the post-war vision of the city. He took to this task with the zeal that earned him the nickname of “road czar.” Cass believed in the car and thought the only people who used public transit were those who couldn’t afford to drive.

“Transit,” he once said, “is not an alternative to the car.”

Cass was integral to the creation of the Gardiner Expressway and Don Valley Parkway, and had plans for other expressways before the city soured on such high-speed, limited-access roads. He also designed a grid of so-called “arterial roads” to carry huge volumes of traffic. Most often, these were four-lane roads and if he had to knock down a few trees and trim some sidewalks to make them fit, well, such was the price of progress.

As his boss, Metro chair Frederick Gardiner once said when critics complained that big, wide roads ruined neighbourhoods: “There have got to be a few hallways through living rooms if we are going to get our metropolitan arterial system built.”

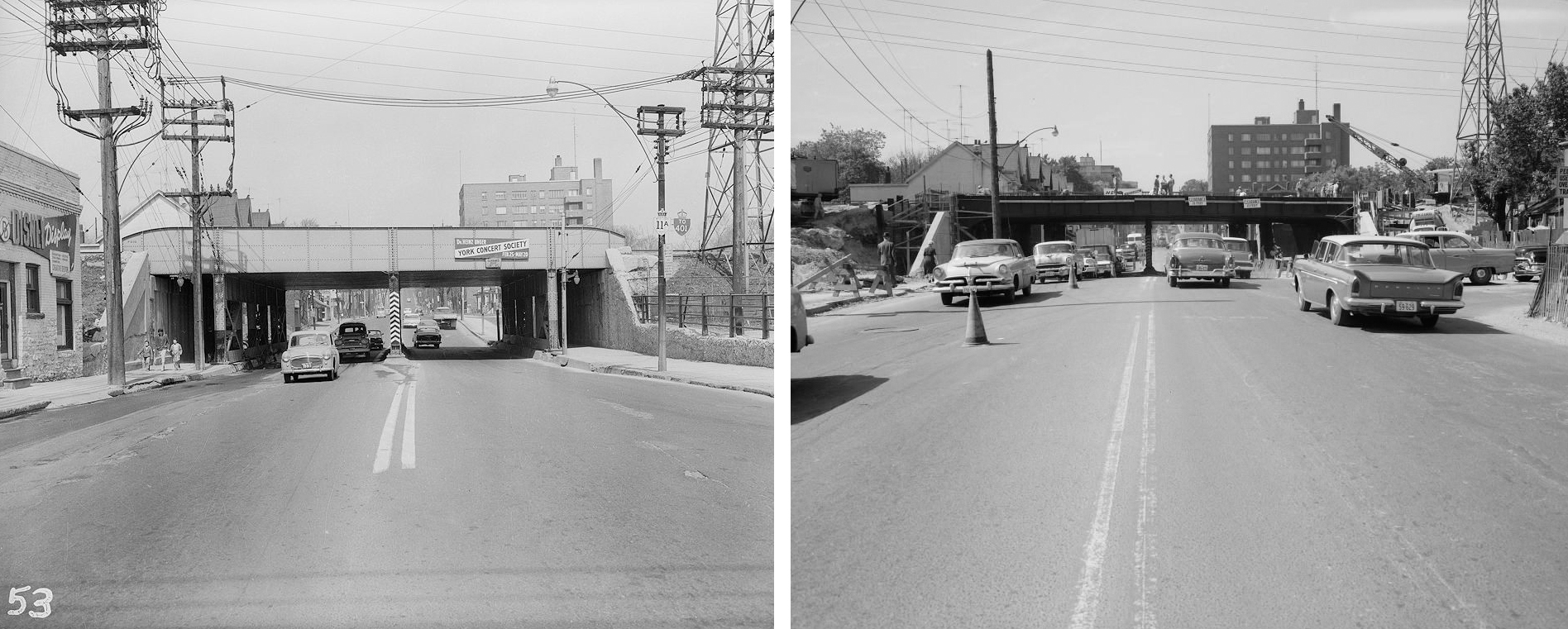

By the time Cass retired in the late 1980s, Metro was responsible for about 688 kilometres of arterial roads. But none was as prominent or integral to Toronto traffic movement as Avenue Road. In the late 1950s, Metro had felled trees and drastically narrowed sidewalks from St. Clair Avenue to Bloor Street West in order to add two more lanes, thus creating a six-lane thoroughfare that has funnelled 30,000 vehicles daily — mostly at great speed — ever since.

Despite growing concern about its impact on air quality, pedestrian safety, and the quality of life of the neighbourhoods it bisects, unlovely and unsafe Avenue Road has resisted change while other schemes from that time, such as the Scarborough Expressway, were abandoned. Despite the later installation of signs and flashing beacons cautioning drivers about the presence of seniors and students, the 2.1 kilometres between Bloor and St. Clair has largely remained unchanged.

Avenue Road, however, may be changing. A coalition of citizens’ groups, the Avenue Road Safety Coalition (ARSC), working with Brown + Storey Architects, has presented a visionary design that would transform the street from a de facto expressway into a pedestrian-friendly, tree-lined boulevard. It would do this by removing one lane of traffic in each direction to create room for wider sidewalks and expansive greenery.

As Brown & Storey state in their plan, the reduction of lanes would allow Avenue Road to be “reinvented for a new generation with generosity, imagination and civic leadership.”

The design makes sense in that there is little reason for the road, which is four lanes north of St. Clair, to suddenly widen to six lanes, only to be constricted again south of Bloor. The question is, will Toronto find the “civic leadership” to do something imaginative that allows pedestrians and cyclists to share the street with vehicles?

It’s a difficult question. Avenue Road has been one of the many third-rail issues of Toronto civic politics. And it seems to carry the deadliest current with politics and politicians, and city staff worried about incurring the wrath of those vigilant about the so-called “war on the car.” Late last year, the Toronto and East York Community Council, responding to public pressure marshalled by ARSC, asked staff to report back by the end of 2020 on a pilot project to increase pedestrian safety by using temporary barriers to expand sidewalk space. There are hints from city staff that a proposal is coming, but if there’s any urgency it isn’t apparent. Contrast that with the warp speed shown by the installation of bike lanes on Yonge Street and on University Avenue south of Queen’s Park.

Area councillors Josh Matlow and Mike Layton supported that pilot project, and have made reassuring noises about the Brown + Storey proposal (which did not involve city planning staff). But Layton was quick to caution in comments to the Toronto Star that it would take time to implement because any reconfiguration would need to coincide with other capital work like sewer main replacement. A major overhaul of Avenue Road isn’t planned for another 20 years but surely interim measures could be taken that don’t involve a major overhaul of the road and its underground infrastructure.

Even with champions on city council, it will be a dog fight to get approval for the Brown + Storey proposal (or something like it) over the objections of councillors from north Toronto and beyond and drivers who are accustomed to flying down the Avenue Road hill to the detriment of local residents and the city’s climate, road safety, and public health goals.

Council will need to decide if Sam Cass and Fred Gardiner’s 1950s vision should rule the Toronto of today or if it’s time to heed the call of residents who want to reclaim their streets and rebuild them according to 21st century attitudes and priorities.

Murray Campbell is co-president of the Rathnelly Area Residents’ Association, which is a member of ARSC.

Renderings courtesy Brown + Storey Architects

3 comments

Davenport Road was also widened to three lanes as well. Currently has painted cycling lanes, but could be better.

If I may be forensically intuitive here, I wonder if there was an external factor motivating Sam Cass to widen Avenue Road–that is, the fact that it was a designated provincial King’s Highway, 11A (and indeed retained that designation into the 1990s, and likely formed part of a red-lined mental geography for many a map-dependent c20 Torontonian). IOW Cass was probably impelled to make Avenue Rd properly “highway-like”, and something that lived up to its original designation as a bypass-like alternative to Hwy 11 aka Yonge Street. (And he likely would have tried to persuade UCC to move, if he could, in order to remove a bottleneck in the 401-to-downtown “clearway”.)

And of course, he was preceded in this by the postwar auto-oriented “improvements” to University Avenue and Queen’s Park Crescent; that is, the balance of 11A going downtown.

Adam, the provincial portion of Highway 11A was entirely within what was then known as North York Township; Otter Crescent is approximately where the line where it entered the old City of Toronto, which both built and maintained the road almost exactly as it is today (although it was in farm fields in 1928).

Also, Highway 11A was transferred to Metropolitan Toronto when it was created in 1954. In fact, after 1954, none of the original King’s Highways through Toronto (2, 5, 11, 11A), except Highway 27 and the QEW, were owned by the province. The Metro government signed the routes until the megacity merger in 1998, after which they gradually disappeared through theft or pole replacement.