The cost of housing doesn’t have to be exorbitant, but it will stay that way as long as the government continues to stimulate the private market rather than creating alternatives to it. Policies intended to help people priced out of the market often end up increasing costs. For example, tax-free down payment plans like the one just announced in the federal 2022 budget will likely drive up prices by allowing more buyers to compete for available units.

To make housing truly affordable, Canada needs to take a different approach. The budget takes a small step in the right direction by promising $500 million of direct funding and $1 billion in loans to create more social housing co-operatives.

Non-profit housing co-ops are mixed-income, multi-unit buildings that are jointly governed by residents. In the early years, seed funding came from unions and churches, but starting in the late 1970s, the federal government provided financial support in the form of government-backed mortgages and subsidies to low-income tenants. People who want to live in a co-op can apply for market units — they pay full rent, but the price is lower than what’s charged by private landlords, since no profit is extracted — or subsidized units, meaning they contribute a percentage of their income, which is topped up by a government subsidy. Once the building’s mortgage is paid off, the fees charged to co-op residents can be quite low because they only cover maintenance costs. The units remain affordable in perpetuity, and the cost of the government subsidy decreases over time.

Co-operative housing is just one part of a broader movement that emerged in the mid-19th century as a way to address the new inequalities caused by urbanization and industrialization. The Rochdale Equitable Pioneer Society was a group of English weavers who founded more than just a co-operative shop. They adopted seven core principles that ensured that economic activity was tied to the needs of members rather than the profit of investors. These principles included open membership, democratic control, rules for allocating profit, and promotion of education. At the core of the philosophy is the idea that property has a social function of ensuring that all members of society flourish.

In a period when homelessness and housing costs have reached crisis levels, it’s time to look to the past to see what solutions have worked. In the 1970s, Canada invested heavily in co-operative housing, and some provinces also implemented their own programs. Today, 125,000 people live in non-profit housing co-ops across Ontario.

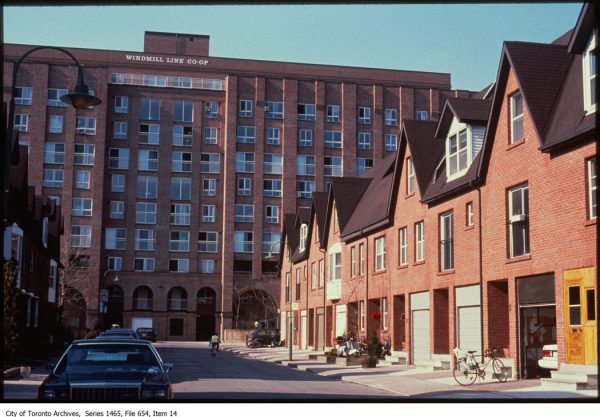

Mixed income housing co-operatives were a key component of the redevelopment of the St. Lawrence neighbourhood in downtown Toronto, which is now considered one of the city’s most vibrant areas. Seventy per cent of the first two phases were developed by non-profit housing organizations, and co-ops continue to anchor affordability in the downtown core.

The relatively small size of the Canadian co-operative sector may lead some to conclude that it’s a nice idea but not a realistic strategy for tackling an enormous problem. Others might argue it’s unfair that some people will benefit from lower costs while others continue to be rent-burdened.

The experience of European countries, however, shows that this approach can be scaled up to provide a comprehensive, fair solution to housing affordability. In Austria, 20 per cent of all housing and 40 per cent of multi-family housing is non-profit. In the capital city of Vienna, 60 per cent of residents live in units either owned by the municipal government or in state-subsidized, non-profit co-operatives. A one-bedroom co-op apartment rents for around $400 in the city. There is political support across the ideological spectrum in Austria, ensuring that the supply of high-quality co-operative housing keeps up with demand.

Given that co-operative housing in Canada has been successful, what accounts for its marginal role in contemporary housing policy? It’s partly due to the economic crisis that hit Canada in the 1980s. Global inflation, industrialization and skyrocketing interest rates led to a government debt crisis, and federal funding for housing programs dried up. When the crisis receded, the market fundamentalism of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher had made it difficult to see government as a solution rather than a problem.

Co-operatives, however, are extremely cost-effective because they almost never default on their mortgages, which is why the federal government expects to leverage $500 million to build 6,000 units. The fine print of the new federal budget, however, reveals that the $500 million is not new funding but rather a reallocation of money from existing programs, and the only $191 million will be spent in the next 5 years. This is a drop in the bucket compared to the $1.4 billion in tax expenditures committed to helping Canadians enter the private housing market.

The Ontario Housing Affordability Taskforce Report proposed streamlining the approval process and loosening zoning rules to make it easier for developers to build more market-rate housing. But the supply of new housing in Toronto has increased at a faster rate than population growth. This tells us that increasing supply alone is not the answer. Nor can we blame foreign investors, who make up only 2.2 per cent of buyers in Ontario’s red-hot real estate market.

The actual speculators are regular homeowners who are leveraging themselves, knowing that capital gains from a primary residence are tax-free. Housing activists also point out that new luxury condos don’t increase the supply of affordable units. In theory, the construction of high-priced units should lower prices by decreasing competition for cheaper units, but in practice it hasn’t worked that way. It’s a good idea to increase the supply of housing by making it easier to build infill projects, but this should be part of an affordability strategy that prioritizes co-operatives.

The goal of housing for all cannot be achieved through the market alone. Co-operative housing offers a viable solution that could substantially ease the housing affordability crisis.

photo courtesy of Toronto Archives: Fonds 200, Series 1465, File 654, Item 14

Margaret Kohn a professor of Political Science at the University of Toronto and author of four books, including three that focus on urban issues. Her most recent book, The Death and Life of the Urban Commonwealth, won the prize for the best book in Urban Politics from the American Political Science Association.

This opinion piece was also published in The Conversation.

One comment

I strongly agree with the sentiment. Going strongly into co-ops is the best solution I can think of for housing our citizens and long-term economic prosperity.

A couple notes on the last portion of the article

“But the supply of new housing in Toronto has increased at a faster rate than population growth. This tells us that increasing supply alone is not the answer.”

There are a couple things here. One is that Ontario has the lowest amount of housing per capita in Canada and I believe also in the G7. That is a huge deficit to be fixed. Supply is the solution, but that supply would have to come in on an unprecedented scale to be effective.

“Housing activists also point out that new luxury condos don’t increase the supply of affordable units. In theory, the construction of high-priced units should lower prices by decreasing competition for cheaper units, but in practice it hasn’t worked that way.”

Cherry picked examples are why this statement can be made. If we take the bigger picture we can see that is has always worked out this way. Look back to the history of the GTA and you can see this. We are currently in a special situation as we are taking in many more immigrants than we have the capability to build housing.

“It’s a good idea to increase the supply of housing by making it easier to build infill projects, but this should be part of an affordability strategy that prioritizes co-operatives.”

100%! All levels of government should be prioritizing co-ops. A simple solution would be to provide the 20% of construction funds to build the projects and remove all taxes/fees. A co-op renting their units at exclusively 80% of the cost to build would provide substantially cheaper rent than is available today. Even at 100% of construction cost (no taxes/fees) would provide substantially cheaper rent than what is available in the market today.