With Edison Gao and Anika Munir

In this “Transit Transformation” series, University of Toronto Scarborough (UTSC) City Studies students lead an investigation into the Scarborough subway extension. Zachary Hyde is a professor in the City Studies Program at the University of Toronto Scarborough. Edison Gao and Anika Munir are students in the City Studies Program at the University of Toronto Scarborough.

On a sunny day about a year ago, a hard-hat adorned Doug Ford posed for a photo-op at the ground-breaking ceremony for the new Scarborough Subway Extension (SSE). The highly-anticipated infrastructure project, which is expected to be completed by 2029, will run along McCowan Road between Sheppard Avenue and Kennedy Station, connecting several of Scarborough’s central neighbourhoods to the downtown core of Toronto.

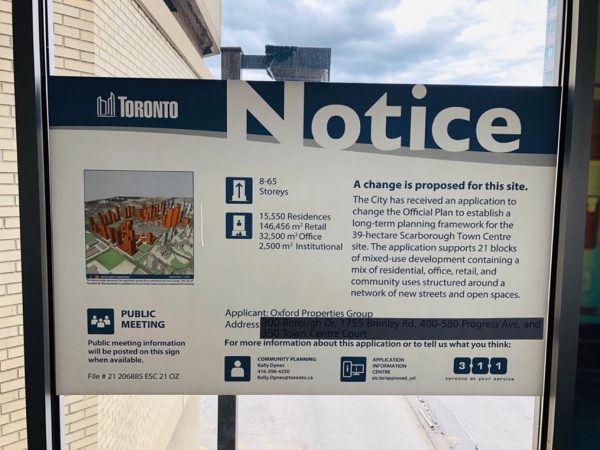

Alongside the transit extension there are extensive plans for development, including a massive overhaul of Scarborough Town Center to build 26 new towers with 15,000 units of housing, and an upscaling of the mall. It is estimated this will quadruple the population in the area. With more multi-tower projects expected between the Eglington Crosstown LRT and the GO Train, the next decade is looking to transform the social landscape of many neighbourhoods.

How will these large-scale and high-density developments impact Scarborough?

In the Spring of 2022, students in my advanced urban politics course at the University of Toronto Scarborough’s City Studies Program did a series of research studies to find out. The class of 60 students, many who grew up in Scarborough, used their deep local knowledge to look at how the transit extension will impact their communities.

They mapped housing options, observed streetscapes and public spaces, drew from census data, and scoured planning documents. The outcome was a series of policy reports about housing affordability, protecting Scarborough’s unique retail and shopping ecology, supporting social infrastructure and community spaces, and ensuring transit justice for all members of the community.

In this series, we want to start a conversation about what policies can help the city flourish as it transforms. Each piece is based on the independent research reports of two or more students in the class. Their ideas, observations, and findings have been brought together to explore, over the coming weeks, different facets of urban life in Scarborough.

Housing and the Scarborough Subway Extension

Anyone who has ventured into the cul-de-sacs that snake off McCowan road can tell you about the most prolific housing type in Scarborough – the single-family bungalow. In recent decades, these homes, which were built largely in the 1950s and 1960s, have provided a gateway to home ownership for newcomers to Canada. Some also contain informal basement suites that provide shared housing for students and other newly arriving migrants.

If you glance over your shoulder from a side street in a cul-de-sac, you may see another key type of Scarborough housing peeking above the roofline – the multi-family rental tower block. These affordable rentals have been providing stability and housing security in Scarborough for many decades.

What will new transit development mean for housing in Scarborough?

Anika Munir and Edison Gao did research to identify the potential housing impacts of the Scarborough Subway Extension along the new transit corridor.

Anika is currently doing a double major in City Studies and Public Policy and has lived her whole life in The Beaches neighbourhood of Toronto. Edison, who grew up on the Danforth and now lives in Markham, is majoring in City Studies, and minoring in Economics. Both Anika and Edison hope to pursue careers in urban planning with an emphasis on housing and creating inclusive and dynamic cities.

For his research, Edison walked, bused, and drove along the new subway line to get a sense of the neighbourhoods from different vantage points. He also used data from the City of Toronto’s Ward Profiles to identify demographic characteristics of the neighbourhood, and Kijiji listings to assess average rents.

Anika also used observational methods in the area around Sheppard and McCowan station, making a survey of the neighbourhood’s housing stock. She used publicly-available information from the 2016 Canadian Census and looked up housing prices on real estate websites.

Alongside this original data collection, both Anika and Edison did extensive research on transit-oriented-development in Canada, looking at data on cities and suburbs like Waterloo, Vancouver, Burnaby, and Coquitlam to identify factors that could also impact Scarborough.

Upscaling Affordability: The Transformation of Multi-Family Rental Towers

If you trace the new subway route, turning North on East Eglinton and heading up Danforth Road, you will come across an increasingly familiar site in Toronto: a block of multi-family rental towers undergoing a face-lift. Resembling a cross between a Liberty Village condo and modernist block housing, the buildings have been painted white with new black cladding. The balconies have new glass barriers, which add an extra layer of sheen.

In their reports on housing options along McCowan Road, both Anika and Edison identified these multi-family rental towers as a key source of affordable housing. Built mostly in the 1960s, they have provided a landing spot for recently-arriving migrants to Canada over many years. However, in the last decade, they have been transformed by a new type of owner: Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs).

Starting in the mid-2000s, real estate corporations have purchased a significant share of the existing rental towers in Scarborough. Their business model is to buy rental housing and sell shares in their portfolio to investors. After this, they engage in a tactic that geographers Martine August and Alan Walks refer to as “squeezing.” This involves making renovations and then raising the rents for existing and new tenants. REIT landlords also are known for adding extra fees to apartment living, such as $70 parking passes for shared lots. Residents have no choice but to pay the increasing rents and fees.

On the one hand, after many years in use, multi-family towers need upkeep and investment. However, the business model of REITs is troubling for Scarborough. Corporations are beholden to investors to maximize profits, a goal which conflicts with the need for affordable housing. While rents in these towers are typically lower than in downtown areas of Toronto, they still place a burden on modest family incomes and risk displacing residents.

With the new subway line coming, REITs and developers certainly saw an opportunity to buy into an area where land values and rents will increase. This has happened in cities like Burnaby and Coquitlam, near Vancouver, where transit-oriented development displaced low-income renters in those areas.

In his report, Edison recommends that regulations be put in place to protect tenants along the Scarborough Subway Extension. The REIT-purchased rental tower complex on Danforth Road is just one of many rental towers near Sheppard and McCowan that have historically been affordable. One option is to apply vacancy control on multi-family rental housing along the SSE corridor, where landlords cannot increase the rent after a tenant moves out. This would mean REITs have less incentive to pressure tenants to leave so they can charge a higher rent to new tenants. As Edison says, this would involve “setting boundaries where rental housing cannot exceed a certain price to ensure that low-income residents are protected from future rent inflation and increases.”

A Known Unknown: Basement Suites as Affordable Housing

When Anika did a street-by-street observational survey of the neighbourhoods around Sheppard and McCowan Road, she noticed the signs of another form housing; an extra mailbox, another car in the driveway, or a side door point to the presence of a basement rental suite. While largely unregulated, basement suites are likely making up a significant stock of affordable housing in Scarborough.

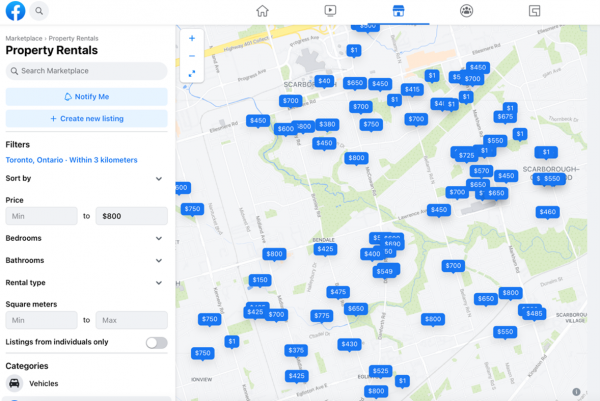

Edison and I did a systematic search of rental prices on Craigslist, Kijiji, and Facebook Marketplace. Along the planned route for the SSE line, we found the most common listing under $800 is for basement apartments. A typical ad is looking for a student or single person to move in with roommates and to split the rent. This is by far the most affordable option for unattached newcomers, who can find a single room for $400-600 per month, compared to $1500 per month for a studio apartment in Scarborough Town Center.

How will the SSE impact this form of housing? It’s difficult to say. As geographer Richard Harris notes, basement suite rental housing in the Toronto region is a black box for researchers and policy makers. While basement suites are legal, the vast majority are not registered with the city. This means that this form of housing is likely undercounted in the Canadian census.

To address our gap in knowledge about this important form of housing in Scarborough, we suggest the city can do several things. First, they can conduct a comprehensive survey of the area to get a better sense of the stock of affordable basement rental housing. Anika recommends that the city factor basement rentals into their policies on transit-oriented densification. When approving mid-rise condominiums and town-home complexes in the area, the city should be mindful this could lead to the displacement of houses with basement rental suites. Unregistered basement suites are an important topic for housing, but can be a sensitive topic for homeowners, who may feel worried about facing legal or financial repercussions for sharing this information. The city’s goal with collecting this information should be to ensure Scarborough will continue to have affordable housing options.

Who will Benefit from Density? The Importance of Picking the Right Rezoning Policies

The biggest anticipated density along the SSE will be the redevelopment of Scarborough Town Center by the major multi-national investor Oxford Properties Group. With such a major project, the city has an opportunity to use its policy tools to negotiate a range of amenities, including affordable housing.

As of now, the city has an inclusionary zoning policy that requires developers produce affordable housing in areas near transit lines. However, some neighbourhoods, like Little Jamaica, have been exempted because the land values are not high enough. Since much of the area around the SSE will likely be rezoned, the city can insist that some of the value created by new density should be used to create affordable housing. This would follow in the policy steps of new zoning frameworks in cities like Burnaby, near Vancouver, where a similar transit-oriented mega-mall redevelopment at Metrotown Centre encourages affordable rental housing construction.

What about the areas on McCowan road between transit stations? Vancouver provides a useful comparison and a cautionary tale. In the lead-up to the 2010 Winter Olympics, the regional transit body, Translink, built the Canada Line, a new rapid transit line between the airport and downtown along the semi-residential Cambie Street corridor. The city then allowed significant extra density for developers who were willing to build rental housing. However, they did not stipulate strong affordability requirements. Only very high-density, luxury mega-projects were required to provide 20% of units at below-market rates.

The rezoning and the transit line increased the value of land substantially all along Cambie Street. Homeowners sold their places for two or three times their previous value, and developers built mid-rise luxury rentals where a one-bedroom now costs upwards of $2000 per month. While the city was hoping that allowing density and new supply would ease the city’s notorious affordability problem, the rents in the area increased significantly.

McCowan Road is similar to Cambie Street in a lot of ways. While the lots are smaller on McCowan, they are prime for land assembly and mid-rise development. Redevelopment is not necessarily a bad idea. However, without careful planning, the city may lose affordable housing to high-end rentals.

Luckily, the City of Toronto has many options. One approach – which was taken by the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts in the U.S. – is to allow for density only if it is used to produce affordable housing on the stretches between stations. This would keep the value of land from skyrocketing, and would allow housing non-profits – organizations that build below-market rate housing – to afford buying the land alongside private developers. It would also ensure that lower-income renters who rely on transit the most, can afford to live near the new stations.

As Anika and Edison have found, the issues of housing affordability in Scarborough are complex, but not intractable – if you know where, and how, to look. With some creative thinking and effort, the city can come up with policies that will allow for housing inclusion, rather than exclusion. The time to start researching and planning is now.

The SSE in Scarborough is set to transform much more than housing. In the next articles in our series, we dive into the unique community infrastructure in Scarborough, and how to the city can preserve and enhance it.

Photos by Zachary Hyde

2 comments

Great article! Well done to the students for carrying out some fantastic research.

“However, the business model of REITs is troubling for Scarborough. Corporations are beholden to investors to maximize profits, a goal which conflicts with the need for affordable housing.”

Unlikely the previous landlords owned rental buildings because of the love in their hearts. Wait a minute, no they didn’t, they have the exact same profit motive! The reason apartments get reno’d and the rents went up is because demand went up without a commensurate change in supply. The owner does not matter.

A lot of this discussion about affordable rental in this article is funny too. Like the million dollar homes near the Canada Line were totally fine but having an brand new apartment that’s affordable to something like 80% of households in Vancouver is a horrible crime. Beyond the IZ is just a form of land lift capture, in Vancouver in many cases instead of IZ, cash was chosen or secured rental covenants in lieu of the below market rental requirements. You can’t have your cake and eat it too and sometimes there isn’t as much land lift being created as you might think.