Recently, the PC government proposed giving Toronto and Ottawa “strong mayor” powers, claiming major cities need strong mayors to deliver priorities. And they might be right. Toronto and Ottawa may need stronger mayors. But what these cities – strong mayor or no – really need are political parties.

Political parties ideologically sort voters and candidates, which creates the legislative majorities necessary to pass laws. As City Council is primarily a legislative body, this is essential to good governance. Toronto is unique among major North American cities for not having political parties. Montreal and Vancouver have non-aligned parties at the municipal level, and most American cities have political parties, whether de jure (New York), or de facto (Los Angeles, Houston, Chicago).

City Councils have a popular image of being beyond partisanship. Fiorello LaGuardia allegedly once said “There’s no Democrat or Republican way to pick up garbage,” which is quoted during debates about political parties and city councils. The argument goes that municipalities have the most visible service delivery – water, power, sewage, and solid waste, among others – and councils should be judged on that record, not on ideological posturing.

Putting aside the fact that no city government should take garbage management advice from New York, which stores mountains of trash in loose bags on narrow sidewalks, these questions are clearly ideological. David Miller’s decision to not break the garbage strike was an ideological choice about a worker’s constitutional right to collective action, and Rob Ford’s decision to expand privatized collection was an ideological choice about the efficiency of the private sector.

Almost every decision made at City Council has an ideological dimension, whether it be land use, taxation, social services, transportation, public space, or others. Local elected officials appeal to common sense, with paeans to community-mindedness or to bipartisan solutions, claiming these approaches to be non-ideological. The issue is, they’re absolutely ideological. An ideology is just a system of ideas, and appeals to gut feelings over interpretations of evidence, loosely defined communities instead of measured demographics, and glad-handing over partisan competition are all ideas that shape the world in particular ways.

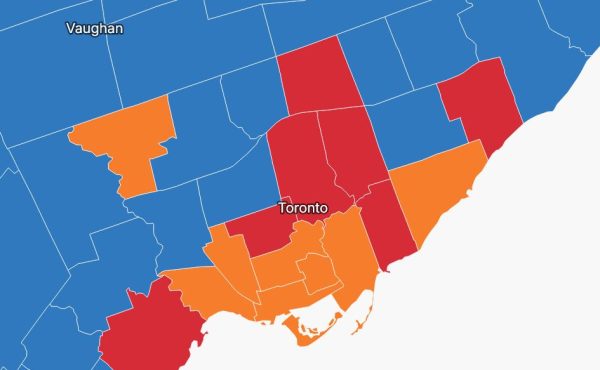

The issue is that partisanship and ideology currently exist at Toronto City Council, but in opaque and inconsistent ways. There is an informal “progressive caucus” that meets on the Friday before council to discuss how to vote on the major agenda items. This is to counter the list that is distributed by the mayor’s office to his allies, which informs every allied councillor how they should vote. Outside observers wouldn’t know that John Fillion, who voted against front doors for secondary suites and was stridently opposed to rooming houses, is on that progressive caucus, but Josh Matlow, who tried reallocate the police budget and liberalize alcohol consumption in parks, is not. This is inscrutable to me, someone who worked for a member of that caucus for 4 years, and must be beyond inscrutable to voters.

There’s also a severe power imbalance between those coalitions. The issue is that the “progressive caucus” is entirely voluntary – there’s no whip, a parliamentary position which ensures ideological discipline. The mayor’s office does have a type of whip, which is executive appointments. If a given councillor doesn’t vote in line with the instruction sheet, they can lose appointments to prestigious boards and committees.

Some voters can try and piece this information together before voting. A lot of voters may remember that John Tory used to lead the Ontario Progressive Conservatives. But how many voters have seen pictures of Josh Matlow or Brad Bradford at Liberal Party events? One of them votes more left than some members of the NDP, while the other is close friends with the Mayor. The mayor himself has many Liberal party supporters. And do many voters know that Paula Fletcher used to lead the Communist Party of Manitoba?

Partisanship exists at City Hall, has meaningful effects on decision-making, and a responsible reform would be to formalize it.

There are many other arguments for parties at city hall, too. Parties increase information dissemination and competition, which are values that appeal to market fundamentalists. Parties can increase diversity and representation among elected officials, which appeal to progressive values. Parties allow upstarts to challenge existing hierarchies, either by joining the party and organizing, or by starting a new party, which can empower those who feel alienated by the current system. Parties won’t solve everything by themselves, but they give voters and organizers avenues to solve problems.

But what really matters here are the issues. The minister of municipal affairs has pitched the strong mayor system as a way to get housing built. And housing needs to get built in Toronto.

What would municipal parties say about that?

Vancouver and Montreal, Canada’s two other major cities, have political parties. Both cities also have housing crises. And both cities have political parties with various positions around the housing crisis. Parties like Projet Montreal and Forward Vancouver can run on their record of governance, and their plans for the future. Their opponents are running on critiques of that record, and plans for a new approach.

Our system favours incumbency bias. In this election, we have an incumbent mayor who on many topics is running against his own record, and is supporting candidates who fundamentally disagree with major portions of his platform. And because there’s no party able to run against him, he and most of his favoured candidates will likely win, and create a dog’s breakfast of policy.

Toronto needs political parties that can present real options to the voters, with a slate of candidates who will pass an agenda. Which individual candidate stands for radically changing our zoning rules? Which individual candidate stands for a public housing builder? And think of every other option on the ballot this year, whether it be property tax, policing, homelessness, public transit, washrooms in parks. These are ideological questions.

What do your council candidates stand for? You can’t get that information from a last name – voters need the ideological signal of party affiliation.

Anthony MacMahon worked as a planning and constituency advisor to Councillor Joe Cressy from 2019 – 2022. He’s also a playwright.

photo by Eric Allix Rogers

4 comments

There’s nothing wrong with being dull.

Want to encourage new candidates? Then adjust the rules for marking ballots.

Allowing people to vote for more than just one candidate (aka Approval Voting) would improve the chances for alternate choices to be elected and it would eliminate vote-splitting.

My name is Peter Handjis.

I am a independant candidate for City of Toronto Mayor in the upcoming October 24 2022 municipal elections.

I am contacting you to gain your opinion on what the city can better do to help with programs and suggestions you would like to see implemented on a city level that can assit your opinion and therefore the residents of Toronto.

I have included my platforms to help you see where I stand on issues at the moment, as elected Mayor. Any suggestions or issues you may have with my platforms please contact me so I can have your input and guidance.

Take note that I am going the way of grassroots in my election campaign to generate interest and dialog with the public as I am currently self funded and I could use all the help I can obtain from people who can put the word out; that there is a candidate for Toronto Mayor who will unabashedly incorporate their campaign platforms into the city’s agenda of things to do.

This message is not necessarily intended to solicit monetary gains for my campaign yet I would not turn it down to sustain my campaign team and volunteers I have right now and looking for additional campaign team expansion both paid positions and volunteers.

I would rather have the ability to catch the attention of organizations and associations already deployed in helping the communities they already serve that match my campaign platforms that can push out my name as a candidate for Toronto Mayor.

Naturally anyone interested in putting the word out on my behalf would probably make an effort to vette me with getting to know me.

In summary I will end with this;

For the city’s planning to be effective for the long term, municipal government shall take the direction of addressing the immediate needs as voiced by residents over the last 8 years and act on these issues and concerns. Conversations can lead to agreements. I strongly believe in this statement. I ask voters to have my back that I may govern as Mayor to have their back.

Peter Handjis candidate for mayor platforms:

Platform 1: To bolster low-income rental options and curb over charging of rental units on the market currently.

Platform 2: To create a subsidy covered by the city to accommodate low-income families and those on benefits live with the expenses of living in one of the most expensive cities in the country where the Provincial and Federal governments are falling short of helping city dwellers.

Platform 3: To encourage, bolster the small to medium business community that care more about the communities they are in than large faceless corporations do.

Platform 4: To educate and equip the emergency services to be more community based. Giving them the equipment and training to be more than just a Band-Aid in the situations they deal with on a daily occurrence.

Platform 5: To upgrade not just play catch up with repairs of the aging infrastructure of the city while paying attention to the disruptions this can cause to neighborhoods and minimizing it.

Platform 6: To help those in high-risk and marginalized industries work more safely in the communities they are in by introducing new by-laws and incentives.

Platform 7:To step up and support the rights of marginalized communities in the city.

Platform 8: To bolster the recovery and addict services in the city to help deal with the scourge of the addiction rampant in the city.

Platform 9: To help frontline organizations and service workers dealing with the issues and needs of the homeless and underhoused members of the city.

Platform 10: To create revenue for the city by building snack shacks and café buildings on city park land to rent out to interested investors. To make the parks safer by creating a community hub of business and customer presence in the parks to discourage crime in and misuse of parks they are in.

Platform 11: To work with trades, businesses and schools to create programs at all levels of education to enable students to have the skills and mentor opportunities to be employment ready when they leave city schools.

Anthony — thanks for writing this. Your point about how the status quo renders things so opaque to voters is spot-on. I’d happy support parties, or I’d at least like to see some cohesive (if impermanent) voting blocs.

One question: Are municipal parties illegal currently? Or is it just custom restraining us?

If a current councillor wanted to run under a party banner (even a party of 1!), is there anything stopping them?

Michael – Our election laws don’t allow anything to appear on municipal ballots besides the candidate names. In BC, you can also list “an elector organization”, which are their equivalent of municipal political parties. This is pretty vital in my opinion – low information voters frequently don’t know the name of their representative, but are instead voting for a leader or a party. You see this all the time when reading mail in ballots and special ballots – they’ll frequently say “Liberal/Justin Trudeau” or the equivalent, despite clear instructions on the ballot saying that you’re only voting for a member of parliament. Not having that information on the ballot could also create some bad incentives – John Smith could be the local nominated member of the “good party”, but John Doe could tell people that he’s the candidate of the “good party” when he’s canvassing at the doors.

There are also big financial barriers. A third party can’t start expensing candidate-specific costs, it has to stay within the third party’s own umbrella. Also you don’t get any rebate for donating to a third party but you do for donating to an individual candidate, so it’s difficult to finance a party.

That being said, even if the whole financial apparatus remained the same, I think if candidates were able to attach elector organizations to their name on the ballot, you’d see a lot of volunteer labour (and maybe the sales of party memberships) doing the work to coordinate a slate of candidates.