While Toronto had the largest streetcar fleet in North America in the late 1960s, TTC planners and management were focused on abandoning the remainder of the network, as was happening in big cities across North America. There were proposals for a subway under Queen Street, replacing what became the busiest streetcar line after the Bloor-Danforth subway opened. In 1969, the TTC released a plan to convert the rest of the network to buses and trolleybuses by the early 1980s, with the vehicles transferred to new lines in the inner suburbs (which never got built). St Clair was the first route scheduled to be abandoned.

However, in the early 1970s, a group of community activists formed “Streetcars for Toronto” in order to lobby the TTC and City Council to retain and modernize streetcars. The group was led by Andrew Biemiller, a professor of child psychology at the University of Toronto. Other members included Steve Munro, Mike Filey, Howard Levine and John F Bromley. The group had support on council from aldermen William Kilbourn and Paul Pickett.

Rather than protesting, they focused their efforts on producing a report highlighting the economic, social, engineering and planning benefits of streetcars, particularly on busy lines. The report argued that because of high ridership on most lines, and the relatively low capacity of buses compared to streetcars, it would be far costlier in the long run to operate buses on most routes, as more buses (and therefore more drivers) would be required.

Streetcars for Toronto released its report called ‘a Brief for the Retention of Streetcar Service in Toronto’ three weeks before the TTC’s meeting on 7 November 1972. This gave plenty of time for the media to cover the report in great detail. The 18 page report also included a short overview of facts for media engagement. At the 7 November session, the board voted unanimously to retain streetcars. It is important to stress, especially in today’s political climate, that the impetus to retain streetcars originated not from the TTC or city council, but from a dedicated group of engaged citizens who conducted their own research and wrote their own report.

Citizen activism to save Toronto’s streetcars was but one of many movements at the time that was led by local residents. Others included the Stop Spadina movement, a city-wide network of resident associations opposed to the demolition of their neighbourhoods, and groups who successfully fought against the demolition of Old City Hall and Union Station. It is also worth noting that one month after the report was released, Toronto voters elected a reform council, led by mayor David Crombie.

After the TTC decided to retain streetcars, two peripheral lines – Rogers Road and Mount Pleasant – were abandoned. The TTC’s attention turned to the streetcars themselves, which were all more than 20 years old. As a temporary measure, 173 PCCs (for Presidents’ Conference Committee) were rebuilt in the mid-1970s.

Compounding the rolling stock problem was the fact that no new streetcars had been constructed in North America since the early 1950s. The TTC looked at some European examples and also the new LRVs built by Boeing for Boston and San Francisco. However, these were rejected by TTC due to their poor running quality and a design that did not meet the city’s needs.

Ultimately, the TTC worked with the UTDC (Urban Transportation Development Corporation), a provincial crown corporation, to develop a new streetcar for Toronto. Known as the Canadian Light Rail Vehicle (CLRV), these entered service between 1979 and 1981. Within less than a decade, Toronto went from being on the cusp of abandoning its streetcars to possessing a brand new fleet of 196 vehicles.

The TTC added to its fleet of CLRVs in the late 1980s acquiring a further 52 ALRVs, articulated versions that predominantly ran on Queen and Bathurst. The network also expanded, with the introduction of the Harbourfront line in 1990 and the Spadina line in 1997, both of which now form the 510 route and operate in their own rights of way.

Toronto’s streetcar network has its share of problems, much of it due to the fact that streetcars have very little priority on the roads and still run in mixed traffic with cars and truck. However, the network’s nine routes form the backbone of transit within the urban core. In 2022, the network has carried over 180,000 riders per day. Remarkably, the 504 King route, which does enjoy priority along its busiest stretches, carries more riders than the five trolley lines in Philadelphia, entire LRT networks in Houston, Salt Lake City, Phoenix and St. Louis, as well as the metros of Baltimore and Miami.

While ridership is still lower than before the pandemic, Toronto’s streetcars remain one of North America’s busiest and most important urban rail systems. The role they play in Toronto today is due in no small part to a dedicated group of advocates and activists who, 50 years ago this month, saw the value of streetcars as an integral part of a growing and dynamic city.

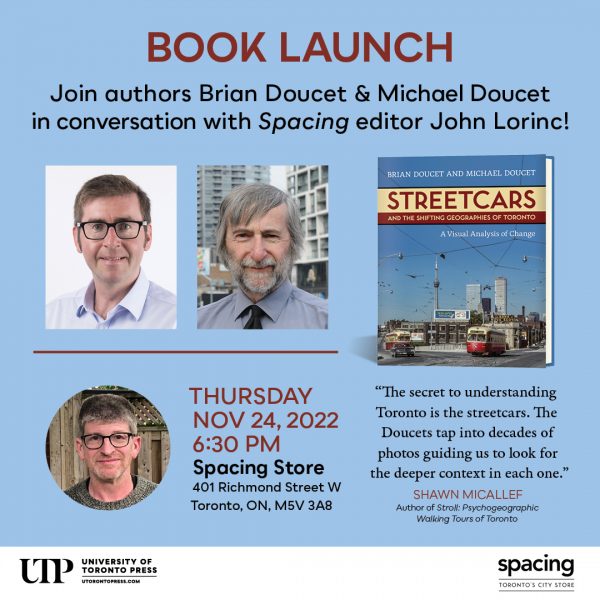

Brian Doucet (on Twitter at @bmdoucet) is the co-author, with Michael Doucet, of Streetcars and the Shifting Geography of Toronto: A Visual Analysis of Change (UTP, 2022). Both Doucets will be discussing the book at the Spacing Store this Thursday, 6:30pm.

One comment

“The network also expanded, with the introduction of the Harbourfront line in 1990 and the Spadina line in 1997, both of which now form the 510 route and operate in their own rights of way.” Splitting hairs here, but while the 509 Harbourfront and 510 Spadina do share part of the Harbourfront right of way between Union and Spadina, they are definitely two separate routes. The 510 goes north on Spadina, while the 509 continues westbound along Queen’s Quay to Bathurst, and then along Fleet Street to the Exhibition loop.