In the middle of a mayoral by-election that includes an idiotic sub-plot about park drinking, Ontario officials yesterday served up this gem: under an agreement with the Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario, 7-Eleven convenience stores will be allowed to sell beer and wine, with the proviso that patrons consume said beverages in new seating areas in their stores (emphasis added).

Imagine: you and your date retreat to the local strip mall to nestle between the ATM and the wall o’ chips under florescent lighting, sipping Ontario plonk. What could be more romantic?

In literally every international city I’ve visited in recent years — in Europe, Latin America, Asia — such a surrealist scheme would bring stares of incredulity or, more likely, outright derision. I was recently in Madrid and Belgrade, and corner stores, no matter how small, all sell spirits, as well as milk, candy and toilet paper. No security guards, or bureaucratic contrivances to discourage customers. The streets aren’t full of dissolute characters. Sky: not falling.

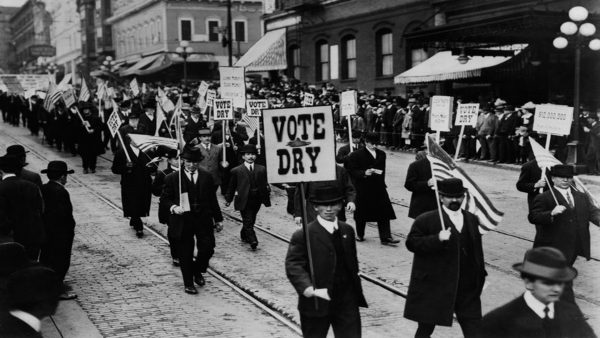

I understand that the AGCO — which, lest we forget, is the direct descendant of Ontario’s prohibition enforcement unit — is a provincial entity, in every sense of that word. But the truth is that such regulations, like those that require cannabis shops to block their windows, are conceived in and primarily for Toronto and Ottawa, the Sodom and Gomorrah of Ontario.

What does this turd nugget have to do with the City’s election campaign?

A few days ago, videoblogger Joshua Hind asked a very good question on Twitter: what, he wondered, is this election really about?

With the eye-wateringly daft 7-Eleven deal in mind, I’d like to offer up this response: the next mayor needs to finally confront and then destroy the world-class provincialism that suffuses so much of how Toronto’s institutions — not people — approach their various mandates.

The first step, as any good therapist will point out, is to admit you’ve got a problem. Toronto, we’ve got a problem. We refuse to let go of the judgmental, parsimonious impulse to use the mechanisms of local government to impose social order.

Heck, we barely acknowledge that this impulse exists.

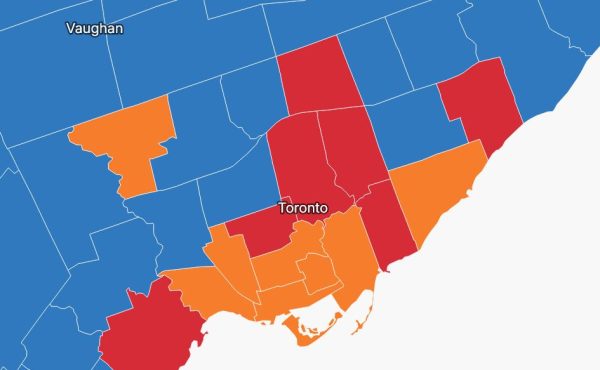

The field of candidates offers little by way of optimism when it comes to this task. Mark Saunders, Brad Bradford and Anthony Furey all seem to be running to lead places like Brockville or Sarnia or Lindsay. From the centre over to the left, I can’t say I see any candidate willing to admit that Toronto desperately needs to extricate itself from the mire of a form of bureaucratic parochialism that is profoundly at odds with this city’s enervating diversity.

Because this is Spacing, I want to focus on public space as both symptom and potential solution. From way back, municipal officials have regarded public space with suspicion and often contempt, and the city’s history — to this day — includes concerted efforts to either destroy or vastly over-regulate public open space as a means of keeping the peace and protecting 19th century social values. We still do plenty of this stuff, but we give those rules different names.

What’s more, there’s a general lack of dot-connecting. We’re having a big and important civic conversation about density and housing. Good. But (apart from Ontario Place), we’re not having the equally big and important discussion about improving the public spaces we’ll need to complement the additional density. The next mayor must — must — make those linkages.

This is about bike lanes, but so much more than bike lanes. An important first step is for the city to stop over-thinking public space. Several years ago, planning and urban design officials expended huge amounts of time and energy developing a so-called “privately owned public space” strategy, which is not only an oxymoron, but a waste of time.

Instead of trying to pretend that the scraps of land next to condos are public, why won’t the city invest serious resources into the basic amenities that improve public spaces: lots and lots of benches and tables, proper park maintenance, bathrooms, etc. The City spends scads of money on playgrounds, which is admirable, but why stop there? Because, well, people other than families with young children will use public spaces and we can’t have that now, can we?

Then there are road allowances. Every little change is made grudgingly and provisionally, or is, as seems to be the case with the new CafeTO fees, designed to fail.

In this campaign, attacks from Saunders and Furey on bike lanes have largely gone unanswered by the left. What’s more, the progressives in the race have said very little, if anything, about the dramatic changes in the way many other big cities have re-programmed their road allowances in the past few years, and not just in response to pandemic conditions.

I recently spent a week in Madrid, which is somewhat denser than Toronto, but not much. After an epic rapid transit expansion program that extended from the late 1980s to the 2010s, the municipality in 2014 moved to significantly restrict private vehicle traffic in the core, both as a public space measure and a carbon measure. Generous expanses of the core are either car free or limited to service vehicles. The streets and the parks are filled with people, the traffic seems very manageable, and retail was booming. Not rocket science.

Hind, in a recent video, made the valid point that it can be annoying to listen to people extol the virtues of cities they’ve just visited. But what’s become ever more apparent is that Toronto’s approach to public space is increasingly the outlier.

Why does any of this matter? Like many big cities, Toronto has an affordability problem, a housing problem and a core that has had a rough ride because of the pandemic and the move to remote work. In a recent interview, the New York Times‘ Emily Badger discussed the brain drain trend that’s become apparent in costly big city metros in the U.S. We have precisely the same problem.

In this new world, public space, and the essential publicness of the big city, is not a nice-to-have, nor is it a realm onto which civic officials should be imposing rigid, archaic values.

The June 26 election is, as many have said, a change election. But what most needs to change, beyond all the obvious policy pieces, is our stultifying Victorian mindset — an outlook that has become utterly incompatible with the urbanism of the 21st century.