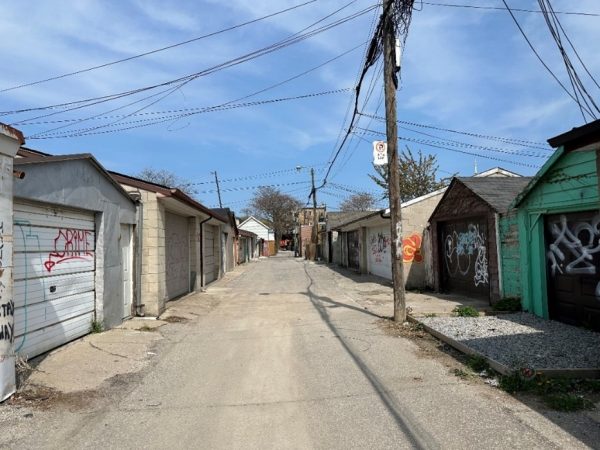

What’s missing in the media coverage about laneway suites is a discussion about the laneways themselves. Currently, they are primarily used for driving, services, and parking; however, with vision, the development of laneways can become a new opportunity to radically transform the older parts of the city. Yet to date, except for examples like like The Laneway Project and a few others, this potential has been mostly neglected and the discussion silent.

The vision is that Toronto’s laneways will evolve into small vibrant streets with a mix of uses that includes housing, commercial activity, workspaces, parking, and local community green space. They are perfectly situated and organized to become a series of mixed-use neighborhoods that interconnect throughout the city. It’s not a far-fetched idea either, as there there are good examples of how this is developing in cities in other countries, such as Melbourne and Auckland, as well as older historical examples like London, England. To bring this about, we need to recognize the opportunity and be bold enough to initiate it.

“Back alleys, neglected courtyards, and stairways may escape our notice … yet if they are claimed, and owned, and developed, they can be harnessed to strengthen and enrich their communities.”

– The Laneway Project

Lanes in Toronto form an extensive network of routes throughout the city. When they were first built in the late 1800s, they were designed primarily for horses and buggies. After those were no longer used, lanes have been used for cars and parking as well as some services like garbage collection. However, in 2018 there was a radical change with the introduction of the new laneway suites by-law that allows people to build housing in them. With this new innovation we have a fantastic opportunity to transform laneways from being service-oriented into becoming a new interconnected network of small local streets where people live, work, play, and move throughout the city. As we see laneway dwellings being constructed, its clear this evolution is already occurring. The important question however remains: how will this transformation affect existing communities and what qualities should laneways have so they become positive local public places?

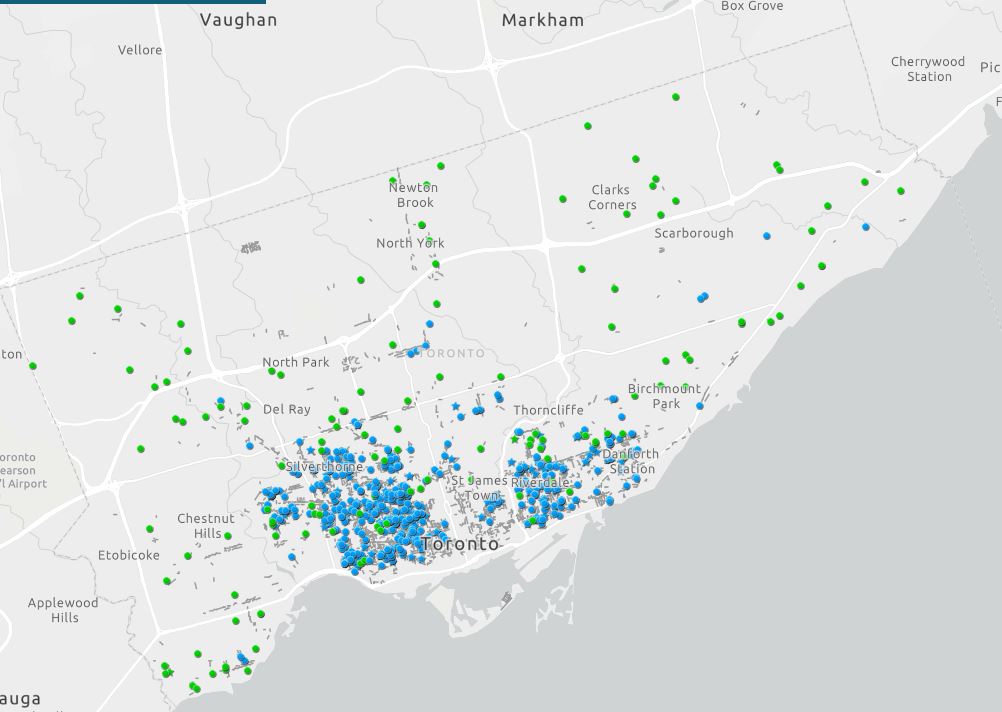

There are roughly 2,400 public lanes in the core of the city, with a total length of over 300 km (see map above). What’s striking about the pattern is the network of connectivity that they form linking one neighborhood to the next. It’s not the same as the street system, and though related, it’s a separate series of routes that form a different type of connectivity. Lanes are more local and smaller than streets. They form a different grid patten, which runs parallel to streets and connects to them. Movement is slower, less direct on a block-by-block basis and they have the potential to develop a more individual appearance than streets. Properly managed, lanes will develop into fine-grained local neighborhoods each with a particular character. They can be mixed-use with small-scale buildings, and can include community green space.

For lanes to evolve into into vibrant mixed-use neighborhoods, the first step is to recognize that they can be so much more than service corridors; we need to imagine them as being people-oriented new communities. The legalization of laneway suites in 2018 was the beginning. For context, at the end of 2022 there were 667 permits issued for new residential buildings in laneways. These are mostly owner-built one at a time and consequently slow to get off the ground. But currently they are being planned and built at an increasing rate. It’s an evolutionary change whose impact you can see walking down laneways and noticing, with the number under construction, how quickly this is catching on. A 2020 TMU study, Analyzing Laneway Housing Potential (PDF), estimated there is the opportunity to build more than 36,000 units of housing. Laneway suites offer the city new housing options that haven’t existed before and could profoundly transform the urban landscape.

Interestingly, Toronto has a rich history of building in lanes for both residential and light industrial uses. These precedents provide excellent examples of how we used certain lanes in the past and how we should begin to think about them in the future. Critical elements in these are: buildings always face the lanes and were accessed from them; municipal services are provided via the lane; and each building is on an independent lot not connected to adjacent house on the street. If we take our clues from these and augment the regulations for new building, lanes will develop into great streets.

Some good examples in the city are: Croft Street, which was a mix of residential and light industrial; Millington Street in Cabbagetown, which was residential; and St Mathias Place near Trinity Bellwoods Park, which was a mix of commercial workspaces, a bakery, and residential.

Prior to Toronto having city-wide zoning by-laws enacted in the late 1940s, it was common that buildings in lanes were mixed use, and they provided space for commercial activities, light industrial, and residential, all of which was legal. After zoning occurred, lanes were seen as substandard for living and working and, as cars began to take over the city, they were delegated as service corridors strictly reserved for cars and parking. They were structured on a suburban idea that different uses be physically separated from one another, and mixed-use neighborhoods were discouraged. When the laneway suites by-law was introduced in 2018, it followed this suburban tradition of separating uses, allowing only residential and limiting buildings to one unit. It was a misguided, outdated idea that needs to change.

There are many ongoing discussions in the city about the lack of housing options, and laneway housing will provide one piece of this. However, to have complete neighborhoods we also need workspaces and businesses close to where people live. Properly designed laneways will be part of this missing link to have walkable community neighborhoods.

Over time there have been numerous conversions of garages into business and apartments, but these have been done illegally and in most cases by property owners who needed an additional residence or a workspace. These have existed for years, while newer conversions occur because rent has become so expensive. As an example of this mix of use, in a lane between College and Dundas near Bathurst, there are three legal lane houses, an illegal furniture repair business, a legal car maintenance shop, and an illegal high-tech startup. These uses mix easily with cars, parking, and kids playing. This model is one we should use as part of the toolkit for making new guidelines of how lanes should develop.

An interesting aspect of these older lane buildings is that they look different from one another, as they were largely built one at a time by the owners. The various uses thrive side by side and each lane has a distinct character. Though contrary to contemporary zoning and city planning, it’s striking how well they work and what fascinating small streets these have become.

Some common characteristics of these lanes that we should emulate are: An absence of sidewalks so cars and people share the same pavement. Lanes should remain narrow, roughly 6m (20ft) to 7m (25ft) across. The principal face of building should be towards the lane and have their front door on it, which keeps it active and safe. Vehicle speed should be 5kph max, roughly the same speed as people walk. Buildings can be mixed use – residential, commercial, workspace, and parking. They should be low scale, generally not more than two storeys in height. In addition, one critical change to add to this list is that laneway buildings have title to their land so they can be bought and sold on the open market.

Cities like Melbourne and Auckland are developing their laneways as mixed-use small streets. This not only increases housing supply but encourages commercial use as well. Cars also use these but they are planned to be pedestrian and bike friendly. Cities throughout Great Britain have many mews behind streets. They were originally bult for horses and carriages, and workers lived above. As times changed these were converted to car parking. During the past decades, as car usage in the downtown core has become less necessary, many of these older buildings have been converted to apartment as well as to commercial and other business uses. Along with newer purpose-built buildings, the mews have become some of the most sought-after streets in London, as well as in other cities in Great Britain. An interesting feature of muses are their distinct character. This is because each building has title to its own land and because they were built or converted slowly over time, so developed independently from their neighbour.

In Toronto, if we encourage the laneway system to develop with clear goals as to what they should look like and the qualities we want, the opportunity exists for them to evolve into new communities where we can live and work all within easily walkable neighborhoods. With good ideas and planning, our 300 km of interconnected public laneways will become a new network of streets that support local neighborhoods.

Some of the outcomes we want are:

- Improve local walkability and connectivity,

- Provide midblock green space.

- Provide access to different housing types and workspaces.

- Be slow moving and safe for everyone.

- Be great places to live, play, and work.

In the future, fewer people downtown will choose to own a car. For many people and for various reasons, this is already occurring, and it will accelerate as we build better transit and have more walkable neighborhoods. Garages will be needed less for cars and can be repurposed or rebuilt to accommodate other uses and lanes will become more pedestrian-oriented. As mentioned, this phenomenon is already happening in other large urban centres that have good transit. Fewer cars are not only better for the environment, but with less land devoted to their single use, it allows our neighborhoods to accommodate more people and be more pedestrian-oriented. With the addition of mixed-use buildings in laneways, these will become complete neighborhoods for the existing community as well. This is a great opportunity and lanes add a critical part to this infrastructure.

To ensure the outcome of laneway design is not haphazard; we need to be clear about the qualities we want. It’s important that local communities are engaged in the process, so neighborhoods develop with a local character. However, certain characteristics need to be consistent across the city. This involves not only the design of the lanes themselves but how we zone the adjacent property. Our current laneway zoning bylaws need to change so they contribute to a positive outcome.

Updated regulations for laneway buildings should include:

- Allow lots on laneways to be severed from the front house as freehold property. This will allow numerous smaller and less expensive houses to be built.

- As of right zoning should include mixed use, including residential, commercial, and light industrial uses.

- All buildings have the option to be multiple units.

- All buildings should be accessed from the lane and have their front door and public face on them.

- Upgrade services in the lanes to include electricity, water, sewer, and garbage removal so that buildings are serviced from them.

- Provide green space in all lanes.

- Lanes don’t need sidewalks but should be designed to have a single, pedestrian-friendly surface.

- Speeds for all vehicles is set to walking speed of max 5kph per hour.

- Make lanes safe, repave them and add adequate lighting.

Currently there is no city-wide plan for what laneways are to become and it is completely off the radar screen. However, we have an amazing opportunity to formulate this vision for what they should evolve into. As lanes are redeveloped and new buildings are added, it will fundamentally alter how we live and move in the downtown core. Without strategic planning, laneways will remain basically as they have been for the past century, service driveways for cars. But with vision and planning, lanes, and the buildings on them will evolve into a new network of local communities suitable for a large urban city of the future with a diverse population.

Photos by Dean Goodman unless otherwise specified.

Dean Goodman is an architect and partner at LGA Architectural Partners. He has been walking the laneways in Toronto since the late 80s.

One comment

Thanks for this piece, which reminds us that while Toronto’s network of laneways is increasingly being put to use to construct much needed new housing, there is also a need to think of the laneways in terms of their ability to evolve from utilitarian serviceways into real places that enrich the city’s urban fabric. I recently constructed a laneway suite behind my home, but the laneway it sits on is still somewhat forlorn and I would love to see it transition over time into a more welcoming environment from the vehicular access that it is today.

I note that, while uncredited to me, the article appears to include an image of my online map of building permits issued by the City for laneway and garden suites. While the underlying permit data is sourced from the City’s open data portal, I have spent many hours extracting and cleaning it to create a compelling and useful resource for those interested in studying the geography of laneway and garden suite construction. Anyone interested in exploring the map further may access it at https://arcg.is/1vTDSz.