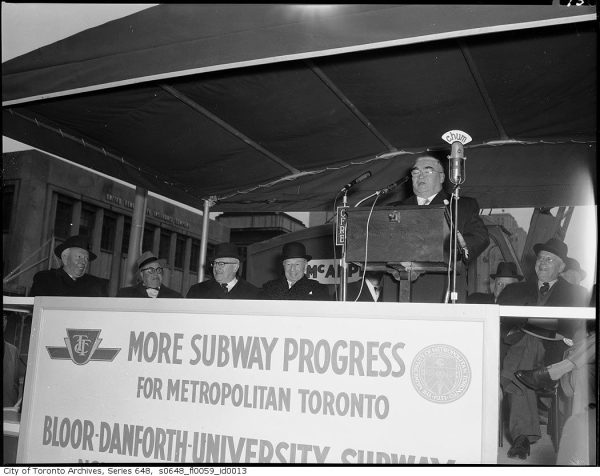

Toronto’s subway system turns 70 this month. Following the completion of the original Yonge line, there was plenty of debate over what rapid transit system to build next, with ideas ranging from a subway line along the Bloor-Danforth corridor to futuristic monorails. This piece, originally published on Torontoist on May 11, 2013, looks at how some suburban politicians within Metropolitan Toronto doubted the financial value of any public transit solution.

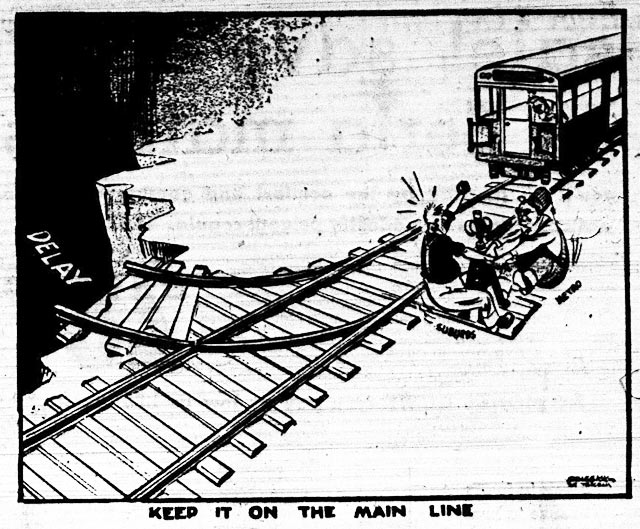

If there is one element of Toronto’s infrastructure that politicians love meddling with, it’s public transit planning. Perfectly reasonable plans are debated to death, delayed, or shoved aside by grandstanding municipal councillors and officials from other levels of government who are convinced they have a better idea. During the planning of the Bloor-Danforth and University subway lines in the late 1950s, politicians from Etobicoke, the western lakeshore communities, and Scarborough were among the loudest opponents. They feared that their constituents would be slammed with tax bills for transit they would never use.

While leaders in inner suburbs like East York, Leaside, and Swansea embraced a new east-west subway to relieve congestion, their western counterparts were less enthusiastic when the TTC posted signs in March 1957 promising a future line along Bloor Street. Objections were mainly financial, with fears that the costs associated with building a new transit line would force cuts to other public works projects. Some officials, like reeves H.O. Waffle of Etobicoke and Chris Tonks of York, felt Metro needed to finish ongoing infrastructure projects before proceeding with a subway. In the small lakeshore communities of Long Branch, Mimico, and New Toronto, officials resented the extra cash commuters paid to travel downtown thanks to the TTC’s fare zone system. “I will never support a Bloor subway until the TTC institutes a single-fare system,” declared Mimico Mayor Gus Edwards. “The outer zones are paying double fares for the present [Yonge] subway and they never use it.”

Funding a subway was challenging, as the federal government refused to offer any money and the province gave little hint of subsidies. Metro Council settled on a formula to split the cost between taxpayers and the TTC, the percentages of which caused months of rancorous debate before settling on 55 per cent Metro, 45 per cent TTC. When Metro council voted to request the necessary permissions from the provincial government, especially from the Ontario Municipal Board (OMB), to proceed with the new subway lines in February 1958, the local councils in Long Branch and New Toronto unanimously passed resolutions to lobby Queen’s Park to ignore Metro’s requests. Long Branch Reeve Marie Curtis felt residents would be hurt by a tax increase of roughly $7 per year. “I fear we are being bamboozled,” Curtis observed. “I am afraid these taxes will tie people up so tightly it will make them move out of here, the same as some of us moved from the city.” Over in Mimico, councillors declared that the new lines would be “of doubtful benefit to our municipality.”

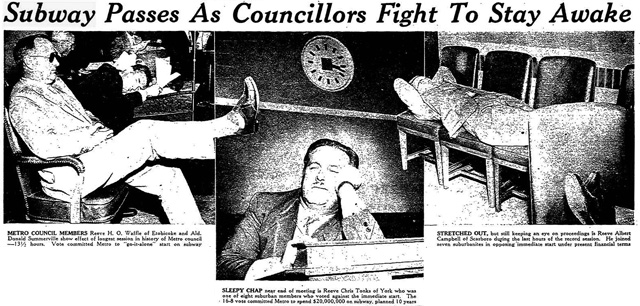

Over the next few months, other suburban leaders doubted the wisdom of financing a subway. Some were riled when Metro Council rejected a monorail system study championed by Tonks and Waffle. During a marathon thirteen-and-a-half-hour meeting on July 3, 1958, Metro Chairman Frederick Gardiner urged his colleagues to “show vision and courage,” citing the Fathers of Confederation and the signatories of the Declaration of Independence for displaying the foresight to support large projects that benefitted all. Toronto Mayor Nathan Phillips felt the “pulse of the people” favoured a subway. Metro Council voted 16 to 8 in favour of commencing work on the subway, with all of the dissenting votes coming from the suburbs. Among the extreme responses was Tonks’ belief that his children and grandchildren would curse him for the debt legacy a subway might impose on York. “Don’t be misled by visionaries who would lead you to believe they see things the rest of us don’t,” he noted.

One by one, six opposing suburbs announced they would oppose the subway during the OMB hearing in August 1958. Despite having discussed subway plans for three years, lawyers representing the suburbs requested a two-month delay to prepare their case. OMB Chairman Lorne Cumming refused. The hearings devolved into shouting matches between the suburban lawyers and a belligerent Gardiner. Beyond taxation issues, subway opponents argued that the project was the first since the formation of Metro in 1954 that didn’t offer “equality of service” to all of its municipalities.

The suburban case suffered a setback on day two when lawyers representing Etobicoke, New Toronto, and Scarborough withdrew, citing lack of time to digest lengthy reports. York’s lawyer went on vacation, leaving only Long Branch and Mimico to carry on. The two tiny municipalities dragged the hearings on for as long as they could, employing filibusters and stalling tactics like subpoenaing TTC officials. Newspaper editorials criticized the suburbs for their obstinacy. Mimico lawyer George Gauld admitted he had “a hopeless task,” but insisted the little guys had to fight on. Within the opposing suburbs, councils voted to ask the OMB to force a Metro-wide public vote on the subway, a power the OMB lacked. Frustrations among subway proponents grew to the point that Toronto alderman Philip Givens sponsored a Metro Council motion to force the amalgamation of the three lakeshore communities into Etobicoke to eliminate their opposition, a move which would happen in 1967.

On September 5, 1958, the OMB ruled in favour of the subway, giving permission for Metro to spend $102.2 million and the TTC $98.6 million to fund the project. They had no qualms with Metro’s plan for a two-mill capital levy on property taxes over the next 10 years. Metro wanted shovels in the ground by year’s end. While newspaper editorials urged officials to get on with it, opponents fumed. Doomsday scenarios about the state of public works and threats of local plebiscites abounded. Edwards believed Toronto taxpayers weren’t as enthusiastic about a subway as generally depicted—“There is only a small percentage of the people who are inconvenienced at the intersection of Bloor and Yonge.

The lakeshore communities, along with Etobicoke and Scarborough, went to the Ontario Court of Appeals to reverse the OMB’s decision. When their attempt was turned down in November 1958, they attacked the local media for politicking in favour of the subway. Scarborough Reeve Albert Campbell felt that past Toronto mayors didn’t act on major issues until they consulted with supportive papers. “This kind of ‘government by the press’ may suit Toronto,” he told the Star. “It is of no interest to us in Scarborough.” Curtis believed the media was out to destroy Long Branch and other small municipalities who opposed the subway.

In municipal elections that December, all of the opposing suburban leaders were re-elected. While Campbell soon switched sides on the subway debate when he saw no further alternatives, Curtis, Edwards, and New Toronto Mayor Donald Russell pressed on. They threatened to go to the Supreme Court of Canada if a flat transit fare wasn’t enacted. The TTC laughed. Councillors in the lakeshore communities continued to resist paying for the line, insisting that their residents had nothing to gain and that full funding should come from the fare box. Lawyers who suggested they should raise the white flag were ignored.

On January 7, 1959, Long Branch, Mimico, and New Toronto filed a Supreme Court appeal against Metro Council, the OMB, and the TTC to halt the subway. Curtis felt assured of victory. A week later, she left a Metro Council meeting in tears after she was voted off the executive committee, on which she had served for three years. Pro-subway suburban councillors, including Campbell, were voted in. Applying the 1950s equivalent of Godwin’s Law, Curtis bitterly observed that “Hitler also tried to stamp out people for what they believed, but he didn’t succeed.” Edwards dubbed her “Saint Marie, the Martyr.”

When the Supreme Court assembled to hear the subway case on February 9, 1959, it considered both the suburban appeal and a Metro motion to quash it. The lakeshore communities, by now admitting the project was all but inevitable, pressed for the project to be financed by 30-year debentures, a move Metro claimed would add $90 million in costs. Suburban lawyers claimed the OMB’s decision to allow a special 10-year tax levy was illegal, that Metro could not force future councils to levy taxes unless they paid off debentures. They charged that Metro could become an “evil godfather.”

The court gave its verdict on February 11, 1959, ruling 3 to 2 in favour of Metro on both actions. There was one slight window of opportunity for further action from the suburbs, as Metro and the TTC had not yet signed an official contract, which could be contested once signatures were applied. Edwards and Russell vowed to fight on, promising to meet with the other lakeshore communities for their next move, including further Supreme Court cases. The TTC used the ruling to give utilities the go-ahead to begin relocating their lines underneath University Avenue.

When Metro Council voted on one of the last obstacles to construction, a new expropriation bylaw, in April 1959, only the lakeshore communities voted against it. Curtis still seethed that Metro won the Supreme Court case on technicalities involving monetary amounts, while Edwards continued to warn the $200 million cost was an illusion. Edwards also opposed early discussions about the Spadina line, sticking to his line that suburbanites were subsidizing subway passengers.

The three lakeshore leaders proved sore losers when they refused to show up for the groundbreaking ceremony for the new subway lines on November 16, 1959. Edwards boycotted the ceremony because “when the people in my municipality are paying two mills a year and a double fare to subsidize subway riders, I don’t feel like celebrating.”

While the transit file didn’t go Marie Curtis’s way in 1959, she left a positive enduring legacy that year. On June 5, Marie Curtis Park was officially opened, on former residential land which had been destroyed during Hurricane Hazel. At the ceremony, she noted that the park showed that “we can go a long way if we pull together. Long Branch couldn’t have done this alone. We needed Metro.” She had also proven the lakeshore communities could pull together, even if they fought a losing cause.

In the end, the provincial government offered a $60 million loan to build the Bloor-Danforth and University lines, which shortened the 10-year construction window. The University line opened in 1963, the first phase of the Bloor-Danforth in 1966, and a Bloor extension into Etobicoke in 1968. The fare zone system was scrapped on New Year’s Day 1973.

We’ll give the last word to Toronto resident Alfred Carswell, whose letter to the Star in September 1958 on the craziness surrounding the subway issue may reverberate with those frustrated with our current city council.

When election time comes around, voters in the suburbs which oppose the subway project should remember the farce their representatives are now putting up in opposition to progress. They state they know they are fighting a losing battle but they will go on with it. It has been obvious for some years that the main transit routes were inadequately serviced, especially Bloor-Danforth and almost to similar degree Queen. One wonders if any of Curtis, Edwards, and Co. have had the experience of literally being pushed into a streetcar with the doors trying to close behind your back. Not once, but most mornings and evenings of the week this jostling, pushing and trampling on people’s feet has been going on for a long time.

Sources: the June 18, 1958, September 6, 1958, February 10, 1959, and April 22, 1959 editions of the Globe and Mail; the March 5, 1957, February 27, 1958, July 4, 1958, August 21, 1958, September 2, 1958, September 6, 1958, November 11, 1958, November 13, 1958, December 10, 1958, January 14, 1959, February 11, 1959, February 12, 1959, June 5, 1959, September 23, 1959, and November 16, 1959 editions of the Toronto Star; and the July 4, 1958, August 19, 1958, August 20, 1958, August 22, 1958, August 25, 1958, January 14, 1959, February 9, 1959, February 10, 1959, February 11, 1959 editions of the Telegram.