Though it normally seems as if the gears of Toronto’s planning machinery are barely moving, the reforms of the past four years add up to what will, someday, be seen as revolutionary moment for a city so dedicated to that most Tory of virtues: incrementalism.

The scope of change leaves no piece of the city untouched: all residential lots are now entitled by law to house up to four dwelling units, including a secondary suite and a garden suite. Parking minimums on multi-unit buildings are gone, as are locational restrictions on rooming houses. Small scale retail is once again permitted in neighbourhoods. The areas around subway and LRT stops, including new ones, are being significantly up-zoned.

The City is using its own real estate to build housing and its coffers to buy older apartment buildings. The feds have cut taxes on affordable rental and are expanding the financial supports for non-profit housing organizations. Meanwhile, homeowner groups now have fewer levers to pull to halt or slow projects they dislike thanks to Planning Act reforms.

Some of these and other moves have emanated from inside City Hall; others were imposed by the provincial and federal governments. All are long overdue, as the intensity of the housing affordability crisis noisily attests.

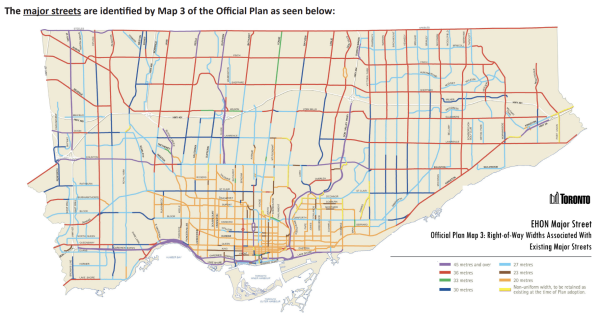

Council this week will tackle the most consequential reform to date with a recommendation to allow the development small-scale apartment buildings (up to six storeys) and townhouses on any “major street” in the city. (The interior of residential neighbourhoods and some strips with “designated neighbourhood parcels” — i.e., single-family homes — remain off-limits to such projects.)

The major streets [see graphic above] include the obvious candidates, as well those roads that have only ever been lined by single-family homes — places like long stretches of Lawrence Avenue West, Ossington, Dovercourt, and St. Clair East, as well as long stretches of arterials in many parts of Scarborough, Etobicoke and North York.

From a zoning point of view, the goal is to provide a much broader canvas upon which moderate scale intensification can occur, as well as an alternative to the re-development ethic that has ruled the roost since the earliest days of amalgamation.

In 2002, council signed off on “the Avenues” approach to adding European-scale density along wide arterials and high-rises in high-growth “nodes” such as Yonge and Eglinton. The thinking, advanced by then chief planner Paul Bedford and embedded in the Official Plan, was that by encouraging mid-rise, mixed-use projects along corridors like Kingston Road, as well as sky’s-the-limit re-development downtown, the City would focus investment in commercial areas and justify transit investment. It could also avoid poking the bear — i.e., homeowners in house neighbourhoods that would remain “stable,” with their “character” intact, for ever after.

The problem with this grand bargain was that the City reckoned it could shoehorn several decades of anticipated population growth into a relatively small amount of space, at least by comparison to the sprawling geography of Toronto’s Yellow Belt.

Over the years since, council has signed off on all sorts of bespoke and time-consuming planning policies (e.g., midrise guidelines, neighbourhood character rules, etc.) that made intensification frustrating and costly even in the areas where it was permitted (bait, meet switch). The upshot: only those with the deepest pockets could afford to play the intensification game, and their investors, consequently, demanded maximum returns.

The “Major Streets” policy — the last instalment of the planning department’s “Expanding Housing Options in Neighbourhoods” suite of land use reform — is meant, more or less explicitly, to dismantle the underlying logic of the 2002 Official Plan. By vastly expanding the places where development can occur, the Major Streets policy basically bets that smaller-scale contractors and investors, including those interested in rental properties, will finally be able to enter a market that has long been out of reach. It’s essentially a supply-and-demand argument.

It’s always crucial to note that while market forces may work adequately for consumer goods, they do not pass muster with housing. For this reason, it’s incumbent on council to learn from the failures of the Avenues and apply those lessons to the Major Streets reforms.

Several come to mind: if the city wants investment, it should incent the type of investment it wants, which means removing the impediments that we know discourage builders. These include troweling on design requirements, approving policies that work at cross-purposes to high-level planning goals, and insisting on a rigid application of the rules.

As I wrote in The Globe and Mail last week, the City is trying to build a missing-middle pilot on a Green P lot in the east end — 28 units across six storeys, with two sets of stacked townhouses behind, all fronting a residential street a few steps from the Woodbine subway station. Because the City is the developer, it must confront nit-picky requirements it imposes on private builders, and hopefully figure out which can be jettisoned without provoking Chicken Little.

There are plenty of advocates for the Major Streets policy, and they’ve been making their views known to the planning department and council. But this being Toronto, there are lots of contras, too — homeowners’ organizations like the Federation of North Toronto Residents Associations, which submitted a 73-page brief itemizing, in minute detail, why the Major Streets proposal can’t possibly work in this area or along that street.

Arguably the single most salient lesson of the Avenues strategy, and the generation of planning studies and design guidelines and official plan amendments that have followed in its wake, is that council must not allow the perfect to become the enemy of the good.

Planner Graig Uens, the architect of the EHON strategy who has unfortunately left the City for private practice, has often made the point that when he and his colleagues were building out the laneway suites policy and then the garden suites policy, their overarching goal was to get something out the door and then deal with the glitches later. (To that end, the planning department has been actively reviewing rejected applications for both types of projects to figure out how to remove roadblocks that serve no public policy purpose.)

It’s too bad Uens is not at the City anymore to impart this critical insight to council and the mayor’s office, so I’ll take the liberty by re-surfacing his argument, and even offering it up to whomever succeeds Gregg Lintern as chief planner later this year.

Planning, after all, is about preparing the city for the future. What better way to proceed than by fully understanding what failed in the past.

3 comments

John,

Thank you for this article. Can you help me understand what this means if an investor/contractor owns a bungalow on a major street that they would like to intensify? Would it be possible to develop a 5-10+ unit apartment on the site, and what documents would the city require to allow this (because I believe I read that an SPA was not required)?

Best,

Sam

Any bus stop, not just on arterial roads, should have at least mid-rises and corner stores.

If a TTC bus stop exists on any street or the street is part of a TTC route, then that street should be developed with mid rise and multi storey residential and commercial buildings.