Given all the powerful arguments articulated by commentators like Elsa Lam, in Canadian Architect, or Alex Bozikovic, in The Globe and Mail, there’s every reason to conclude that the Doug Ford government’s abrupt and unjustified move to shutter the Ontario Science Centre last Friday is yet another disgraceful example of its taste for demolition by neglect.

Ford and his infrastructure minister Kinga Surma seem to know exactly how they want this story to end. Meanwhile, the rapidly swelling ranks of those opposed now includes individuals who are offering, quite remarkably, to pay for the roof repairs out of their own pockets in order to keep the pioneering institution open to school groups, tourists and local residents.

How this confrontation resolves in the short term is anyone’s guess.

What I’d like to focus on, however, is the longer term, and the role of this complex of iconic buildings in what will become, two or three decades hence, a dense hub with tens of thousands of new apartments and offices, all served by one of Toronto’s few rapid transit interchanges. Once the Ontario Line and the Eglinton Crosstown are up and running, the intersection of Don Mills and Eglinton is certain to evolve into a bustling city-centre, potentially like Yonge and Eglinton, North York City Centre or Scarborough Town Centre.

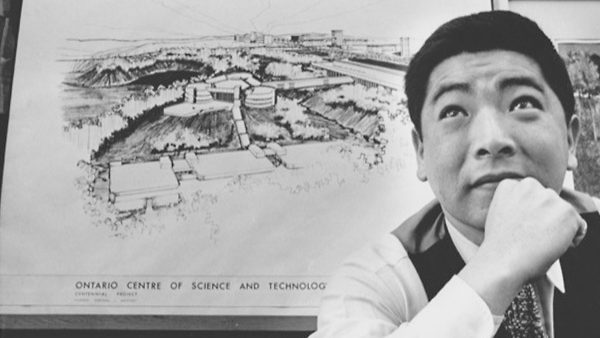

To my mind, there are two parallel but not entirely overlapping issues at play here: one has to do with the future of the Science Centre as an institution and the other involves the future of Raymond Moriyama’s exceptional building.

Ford & Co. are obviously determined to relocate the institution to Ontario Place, in the face of a growing stack of reports and audits recommending otherwise. Yet as even Queen’s Park concedes, such a move doesn’t preclude the existence of an OSC satellite on the current site. Indeed, many great museums operate multiple sites, and there’s no reason why the OSC shouldn’t have a second location programmed more specifically at school groups, for instance.

If we accept this change — and I respect the fact that many people don’t — then the City and Queen’s Park have an generational opportunity to engage in a much more forward-looking dialogue about renovating and repurposing parts of a very large structure such that it serves the needs of a populous community centred on Don Mills and Eglinton.

Toronto, of course, has a terrible track record when it comes to protecting its architectural heritage from the wrecking ball. But when we’ve figured out how to save old buildings, we do a respectable and even imaginative job at recycling them. Think of examples like the Wychwood Streetcar Barns, the Distillery District, Queen’s Quay, York’s Glendon campus, several theatres, and the Brickworks. There’s no reason the OSC can’t join this club.

Moriyama designed the OSC in three distinct but interconnected parts, and these have been expanded further over the years to produce a highly modular complex, not all of which has architectural value (e.g., the back-of-house structures on the lower level). With some imagination, it isn’t difficult to envision the OSC re-configured to house multiple community facilities and services, as well as an OSC satellite, all while preserving and restoring the unique parts of Moriyama’s architecture.

What might be on the list of tenants? A library for sure (there are none in the area), offices for local non-profits, performance spaces (e.g., the high-ceilinged interiors of the display halls), artists’ studios, recording facilities, affordable programming spaces for community groups, health clinics, etc., etc.

It’s true the City is in the middle of a meandering exercise to build a new community centre on the old Celestica site, on the north-west quadrant of the intersection. The funding comes from Section 37 grants tied to the redevelopment planned for that property and others nearby.

The planning process for this facility began in 2018 and likely won’t produce a functioning building until 2030. When it opens, the new Don Mills Community Recreation Centre, like most such Parks Forestry and Recreation projects, will primarily serve as a sports facility, with rinks and pools and gyms, plus a bit of generic rental space at the edges.

I have no problem with sports-based recreation facilities, of course, but no one should pretend that this community centre alone will meet the demand for all the many sorts of non-residential/non-commercial spaces required to serve the sustained influx of new residents and families to what has long been an under-served neighbourhood. What’s more, the flow of funding for such amenities will slow significantly in coming years due to provincially mandated reductions to development levies that have long been used to fund community spaces.

We know all too well how school boards and the provincial education funding formula have dramatically short-changed vertical newcomer communities in places like Flemingdon, across the street from the OSC, or Thorncliffe Park (e.g., Grenoble Public, a JK-6 school that’s a 15-minute walk from OSC, will be at 158% capacity by 2025, according to Toronto Lands Corp.). While the TDSB is considering a new public school in this area, the planning is highly preliminary and it’s a safe bet that lots of the newly planned towers will go up long before it gets built.

You don’t need to look too hard to find earlier examples of dense vertical neighbourhoods built without adequate local amenities/services (e.g. St. James Town), and whose low-income/newcomer residents suffered for years as a result. Toronto also has a stellar example of the opposite in St. Lawrence, which was developed from the get-go as a complete community. The new Regent Park was also rebuilt with a keen awareness of the importance of third spaces.

My point here is that if city and provincial officials can see beyond the political sparring over the location of the Science Centre, they could commence a constructive planning exercise that would save a valuable heritage structure, avoid the massive amount of waste and carbon generated by demolishing and then redeveloping a huge building, and create the kind of community infrastructure that becomes incredibly costly to shoehorn into mature neighbourhoods. As the saying goes, not an either/or but rather a both/and.

Yes, such a directional shift will require capital investment and involve some technical complexity. But these are by no means insurmountable obstacles. The tab at the end of the exercise will surely be less than what it would cost to start from scratch. And the real dividends, in terms of community building, will be measured not in dollars but quality of life.