Like Toronto’s winding ravine system, the Toronto waterfront is a significant and defining geographical feature. Before the arrival of Europeans, Indigenous peoples flourished on the land that would much later become the City of Toronto. For Indigenous people, the waterfront served as a direct route to the St. Lawrence River and the Upper Great Lakes, thereby enhancing trade and communication within the traditional territory of its various nations, including the Mississauga of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wendat Peoples.

As described in the Waterfront Toronto history page and other sources, the arrival of European colonists marked a significant change for the Lake Ontario shoreline. After the American Revolution in 1776, Toronto emerged as a logical site for the British to establish a naval base to protect Upper Canada from the threats posed by the new American government. By 1793, with the building of Fort York, the town of York established itself as a protected, active and reliable port.

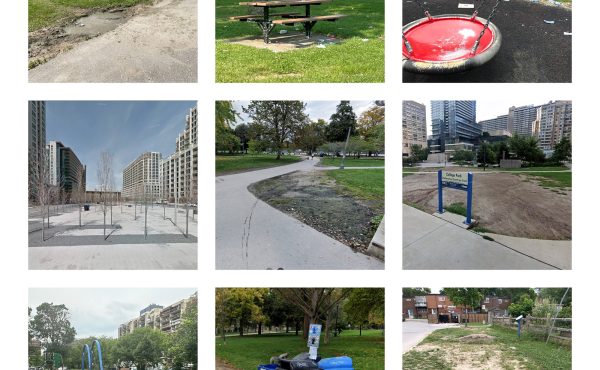

(Click on the images below to view the photographs full size.)

York’s success as a port fueled rapid growth, resulting in a need for enhanced shipping facilities to accommodate increasing demands. Starting in the 1830s, a 120-year process of infilling the original Toronto waterfront extended the shoreline to its current location. During this time, the extent of Toronto’s harbour grew alongside its industrial use, leading nearby residents to move further from the city core. This shift, driven by the rise of the automobile and the construction of highways, enabled workers to commute from the suburbs. One notable route to the city, the elevated Gardiner Expressway, was constructed in 1950, effectively creating a physical boundary between the city and the waterfront.

For the next twenty years, the harbour began to lose its significance for shipping and manufacturing. In response, Toronto residents started to envision that the waterfront could be reclaimed for new, attractive public uses, including parks and cultural facilities, as well as for business and residential development. Today, assessing the overall success of this ongoing endeavour to regenerate the waterfront is challenging. Individual achievements are numerous, as are some serious mistakes.

In 1984, as a graduate student, I created some of my earliest photographs of industrial architecture at Toronto Harbour for my thesis project. In the years that followed, I periodically returned to the waterfront to document the ongoing transformation driven by efforts from government and private interests to improve public accessibility to these areas.

Considering the significant developments over the years, now seems an appropriate time to explore the waterfront’s current state more closely.

These photographs are samples from my latest photographic excursions to document the Toronto waterfront—a project I will continue over the coming months. Geographically, the area I will cover stretches from the shore of Lake Ontario in the south to the Gardiner Expressway in the north and from Cherry Street in the east to Dufferin Street in the west. Assuming all goes well, I plan to exhibit the work in the fall of 2025.