Yonge street is very much the spine of Toronto. The city has grown up along and from it, with successive arterial roads radiating outwards like ribs. It’s a line that both divides the city, and its streets, into east and west – marking the beginning of address numbering in each direction – and that ties the city together. As it moves from the lakefront to the city’s northern border, Yonge evolves constantly, at each point reflecting the nature of its new environment, and so showcasing many of the different phases of our vast metropolis.

Like a spine, Yonge is also the city’s nerve centre, the place that gathers the city’s energy and population when there’s an upheaval – whether it’s to celebrate a sports championship or the end of a war, start a rebellion or a riot, or mark a shift in the spirit of the times through a subway, pedestrianization, or parades.

It’s also the street people newly arriving in Toronto are most likely to know about. In practice, it hasn’t necessarily lived up to its renown. Yonge has not always been treated with the respect its central role deserves, sometimes being neglected and even despised. But at the moment it is undergoing significant evolution, reflecting changes in the city as a whole.

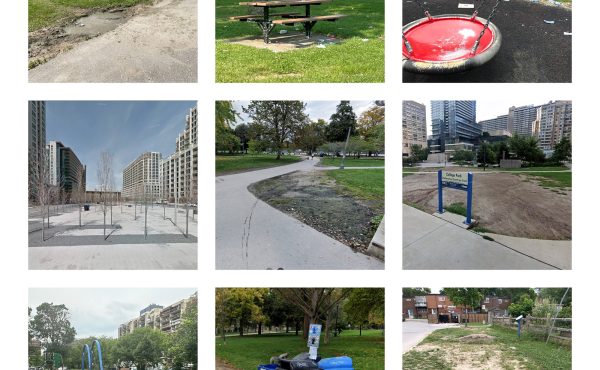

Among those changes is rapid development, as condo towers spring into the air along the street like the blades on the back of a Stegosaurus. At ground level, long-standing low-rise main street buildings with small shops are giving way to modern, glossier and glassier frontages – although the old buildings are sometimes restored in the process, kept as souvenirs of earlier streetscapes. Both downtown and in North York, changes are envisaged to make the street more oriented around people and less around cars (although the provincial government may get in the way). Underground, meanwhile, plans are being developed to extend the subway – Toronto’s original line – north to the border of Toronto and beyond.

Given its central role in Toronto, we wanted to dedicate a cover section to Yonge Street, capturing its many different states. How does it reflect different parts of the city? How do people use it or treat it? How has it evolved over its over two centuries of history? What changes are happening now, and what do they mean for the street and the city?

Our tour of Yonge street begins with an orientation by senior editor Sarah Hood, who helped design Yonge Street’s 200th anniversary celebrations in 1996, and then a bookish overview by a visitor from the Maritimes. We then work our way up the street, stopping at some key locations for our writers explore their changing nature. We don’t have space to cover every part (we’ll get back to Yonge at Eglinton when we feature that key east-west route next year), but even what we do cover gives a strong sense of the street’s geographic and chronological evolution. And throughout the section, that transformation over time is chronicled in a running timeline by Jamie Bradburn.

In our front section, we also explore some anniversaries. We talk to Winter Stations, the art project that brings life to a chilly Woodbine Beach every February, about its first ten years and what the next ten years might bring. Twenty years ago, meanwhile, we launched our wildly popular Spacing subway buttons, and our editors reminisce about their origin and their influence over the decades.

Another important milestone this year is the opening of the Spirit Garden at Nathan Phillips Square. Theo Nazary and Andrew Chiu guide us through some of the symbolism of its features and how they recognize Toronto’s Indigenous history and the trauma of the residential school system. It’s the kind of place Somia Sadiq advocates for in her op-ed on the necessity of trauma-informed planning.

Other pieces in our front section build on the theme of how the city can impact us. An excerpt by Claire Steep from the new book Living Disability, edited by sometime Spacing contributor Emily Macrae, takes a wry look at the challenges of regional transit for those with partial sight. And Jessica Patterson asks if adding a bit more civility to our driving would not only leave us less stressed, but also less congested.

The city isn’t just challenging for humans, though. We featured the FLAP (Fatal Light Awareness Program) in one of our first issues, and tragically is it still needed. In this issue, we return to this program through Matthew Hanick’s profile of photographer Patricia Homonylo, whose arresting photographs of birds killed by collisions with glass buildings advocate for the program’s efforts.

As you fly through this issue, however, we hope you’ll experience a peril-free overview of this city and the spine that runs through its centre.

This issue is available now at the Spacing Store at 401 Richmond St. W., and soon at fine book and magazine stores, as well as arriving soon in subscribers’ mailboxes.