Though it seems like an eternity ago, Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives circa 2023-24 desperately wanted this election to be about the ruinous cost of housing (and Justin Trudeau, of course). Poilievre starred in numerous extended and effective videos — e.g., “Housing hell: how we got there and how we get out”‘ — dramatizing the myriad ways in which the housing approvals system had gone off the rails.

Municipal “gatekeepers,” according to his narrative, were gumming up approvals and imposing brutal development levies, with the result that young people across Canada now found themselves frozen out of the housing market and condemned to a life of rental penury — never mind that the Liberals had allocated tens of billions in loans and subsidies via their National Housing Strategy (NHS).

That, in the event, is how it started.

Trudeau, in short order, demoted his housing minister (Ahmed Hussen), replaced him with a new and more visible spokesperson (Sean Fraser), who amped up the comms, helped himself to some of Poilievre’s housing planks, and effectively neutralized that component of the Conservative campaign.

How it’s going?

Well, to state the blindingly obvious, we’re not having the election Poilievre craved so badly, and housing affordability isn’t playing a starring role, although the parties in the past week have begun to plant their flags in this space.

Both the Liberals and the Tories have pledged to, uh, axe the GST/HST on homes, up to $1 million and $1.3 million, respectively. Such promises may have some curb appeal, politically, but they won’t do much to dent housing prices.

Potentially more interesting are pledges by both the NDP and the Liberals to re-invent CMHC — the sprawling federal bureaucracy that offers mortgage insurance, carries out housing research and administers all the funding that has flowed through various NHS programs.

The NDP, which has long flirted with the notion of nationalized financial institutions, wants CMHC to become a lender, not just an underwriter, with the stated aim of providing lower cost mortgages to homebuyers.

For a party in freefall, the details of this idea are unimportant. Suffice it to say that establishing a public sector bank would be an extravagantly complicated journey, one crisscrossed with bureaucratic tripwires (who regulates it? will it have to meet the kind of exacting regulations Ottawa imposes on private banks? will it be able to offer other financial products, such as home equity lines of credit?).

The Liberals, in turn, want to hive off the piece of CMHC that builds housing — mainly the modular transitional housing projects established under the Rapid Housing Initiative — and create an entirely new public sector developer, dubbed Build Canada Homes (BCH), fitted out with $25 billion in debt financing. According to the Liberal policy document released Monday, “BCH will have three key functions: building affordable housing at scale (including on public land), catalyzing a new housing industry, and providing financing to affordable homebuilders.”

Carney’s goal: 500,000 new homes per year, to be constructed on public land in partnership with affordable housing providers, and using a Canadian supply chain for materials ranging from mass timber to pre-fabricated units.

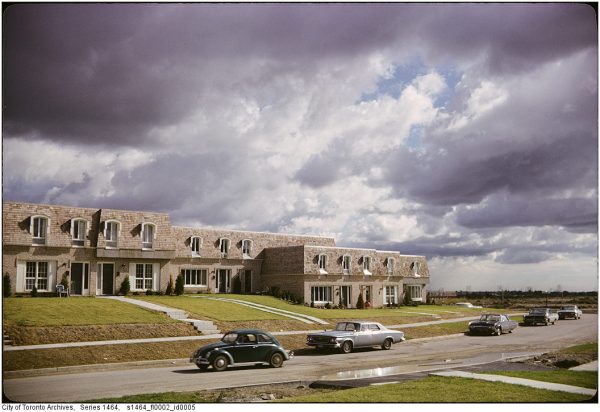

The Liberals have pushed out messaging steeped in both nationalism and nostalgia, repeatedly citing Ottawa’s post-World War II campaign to build a massive amount of housing for returning soldiers. That heroic effort turned on CMHC-produced catalogues filled with the templates for basic homes, plus an offer that allowed buyers to secure low-cost, government-backed mortgages if they selected one of the homes in those pattern books.

Yet the Liberals’ historical narrative is a bit muddled. As I explain in the current issue of Canada’s History, the federal government’s first foray into wartime housing involved the construction of tens of thousands of rental dwellings, for veterans as well as people working in wartime industries, built by a fleet-footed crown corporation, known as Wartime Housing Ltd., run by a Hamilton contractor, Joseph Piggot.

Ottawa’s better known and much romanticized post-war housing push was entirely focused on home ownership and private land sales. Prime Minister Mackenzie King didn’t want the federal government to become a large-scale landlord, asserting that such an operation smacked of socialism or communism. In fact, it seems that Carney’s plan is more akin to the one King rejected, although without, obviously, the ideological bogeymen.

What’s more, the Liberals’ housing platform raises lots of practical questions, not least of which is how a national, publicly owned developer will operate, especially when tasked with striking partnerships with affordable housing providers. Carney says BCH will build on publicly owned land. But the federal government’s own inventory shows that much of this real estate portfolio has been sold off, with only 90 parcels in the current land bank, totalling 473 ha — three High Parks, if you’re doing the math — across Canada.

The platform also talks about slashing municipal development charges by 50% on multi-unit residential buildings, but is far from clear about how it would encourage/compel/coerce local councils to take such steps. The plan only says, in passing, that a Carney-led government will “work with” provinces and territories to help make up for lost development charges revenue, presumably in the form of increased infrastructure funding. Yet that quid-pro-quo only works if the federal transfers find their way into municipal coffers, which is by no means a given, especially in Doug Ford’s Ontario.

Finally, the Liberals are promising to re-introduce a tax incentive for rental apartment buildings, based on one that, they say, generated 200,000 units between 1974 and 1981.

In fact, the great slab apartment building boom — particularly in Toronto — began in the late 1950s. This explosion of high-rise modernism was driven in part by Metro Toronto’s regional plan as well as the existence various financing incentives and a tax shelter that allowed non-real estate companies and wealthy individuals to reduce their taxable income by claiming depreciation losses from the apartment buildings they invested in.

Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals in 1972 closed some of those loopholes and narrowed the range of tax filers who could claim losses on apartment buildings. Just two years later, they re-instated some of those same incentives with the Multi-Unit Residential Building Program with the stated goal of kick-starting rental construction — which had flat-lined — and boosting employment. According to ERA Architects partner Graeme Stewart, the MURB Program yielded 344,410 units between 1974 and 1981 — a period of unrivalled expansion. Subsequent federal programs fell flat, and eventually Ottawa — thanks to first Brian Mulroney’s Tories and then Jean Chretien’s Liberals — exited affordable housing altogether.

It’s worth noting that when investors flocked to park their capital in these slab buildings half a century ago, they didn’t have options, like condos or REITs. The wrinkle for Carney’s plan, therefore, is to create — or re-create — a tax incentive that is attractive enough to draw capital away from other real estate investment vehicles, but do so without creating perverse outcomes. There’s perhaps a reason why previous governments haven’t figured out how to square this circle.

Still, Team Carney gets points for at least laying out a platform with the ambition to take a somewhat different tack, not just from Poilievre’s pledge to cut taxes and gatekeepers, but also from the housing schemes advanced by Justin Trudeau’s Liberals, which leaned heavily on forcing billions of dollars in grants through the funnel that is CMHC. Whether it sparks a post-war building boom, of course, remains to be seen.

photo courtesy of Toronto Archives