Nathan Phillips Square is one of Toronto’s most iconic landmarks – its open plaza and the modernist curves of City Hall are fixtures in the city’s visual identity. In winter, the space buzzes with energy as tourists and locals circle its famous skating rink, zipping past the now-iconic Toronto sign. But summer is different. On hot days, the open field of concrete slabs bakes in the sun, and visitors retreat from the radiated heat to the modest shade at the edges.

This seasonal imbalance of design in public spaces is also emblematic of Toronto. The city has long identified as a winter city, and many shared spaces are designed to maximize sunlight in the colder months, often at the expense of summer shade. This approach is increasingly at odds with a warming climate.

Cities around the globe are grappling with changing weather patterns. Some have hired Chief Heat Officers to steward their responses to extreme heat. In cities like Dubai, Athens, or Seville, maximizing shade and channeling wind through the built form for cooling are the focus. Similarly, designing for a cold Nordic city can be straightforward. But cities like Toronto must contend with both freezing cold and blazing heat as they balance comfort throughout the year. And that won’t get any easier. According to a report by the Climate Risk Institute, the number of days over 30 degrees Celsius in Toronto will increase from an average of 16 today to between 55 to 60 by the 2080s.

To help with these design challenges, the City of Toronto has completed a study to address thermal comfort in its public realm.

Thermal comfort – essentially feeling neither too hot nor too cold in an environment – is something of a forgotten art in design. In the first century B.C.E, the Roman architect Vitruvius wrote about climate in relation to design, and how to place and build a space for optimal comfort. But in recent decades, the comfort of public spaces is often crowded out by other concerns in the complex balancing and budgeting of urban design. Designing for thermal comfort is crucial in a city that is getting bigger and denser every day, and for citizens increasingly reliant on shared public spaces for recreation and relief.

The study is a collaborative effort between Toronto City Planning and a consulting team led by DIALOG and Buro Happold. It’s only the second initiative of this kind in the world, and the first in North America. The study produced, and City Council adopted, a report called Thermal Comfort Guidelines: For Large Area Studies, Public Realm Capital Projects, and Large Site Developments. The team defined how best to measure thermal comfort at any given site, including the consideration of future climate projections, and created a toolkit of design ideas for a thermally comfortable public realm.

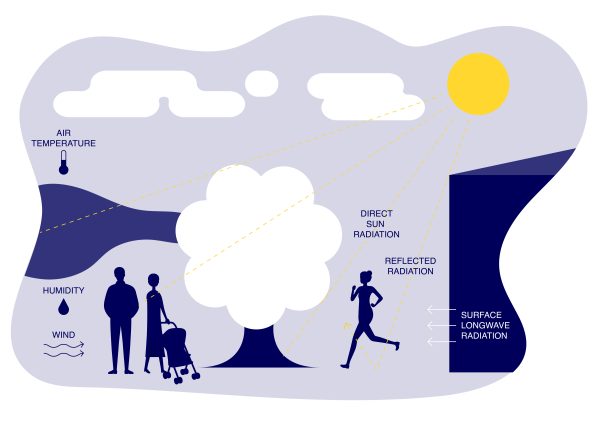

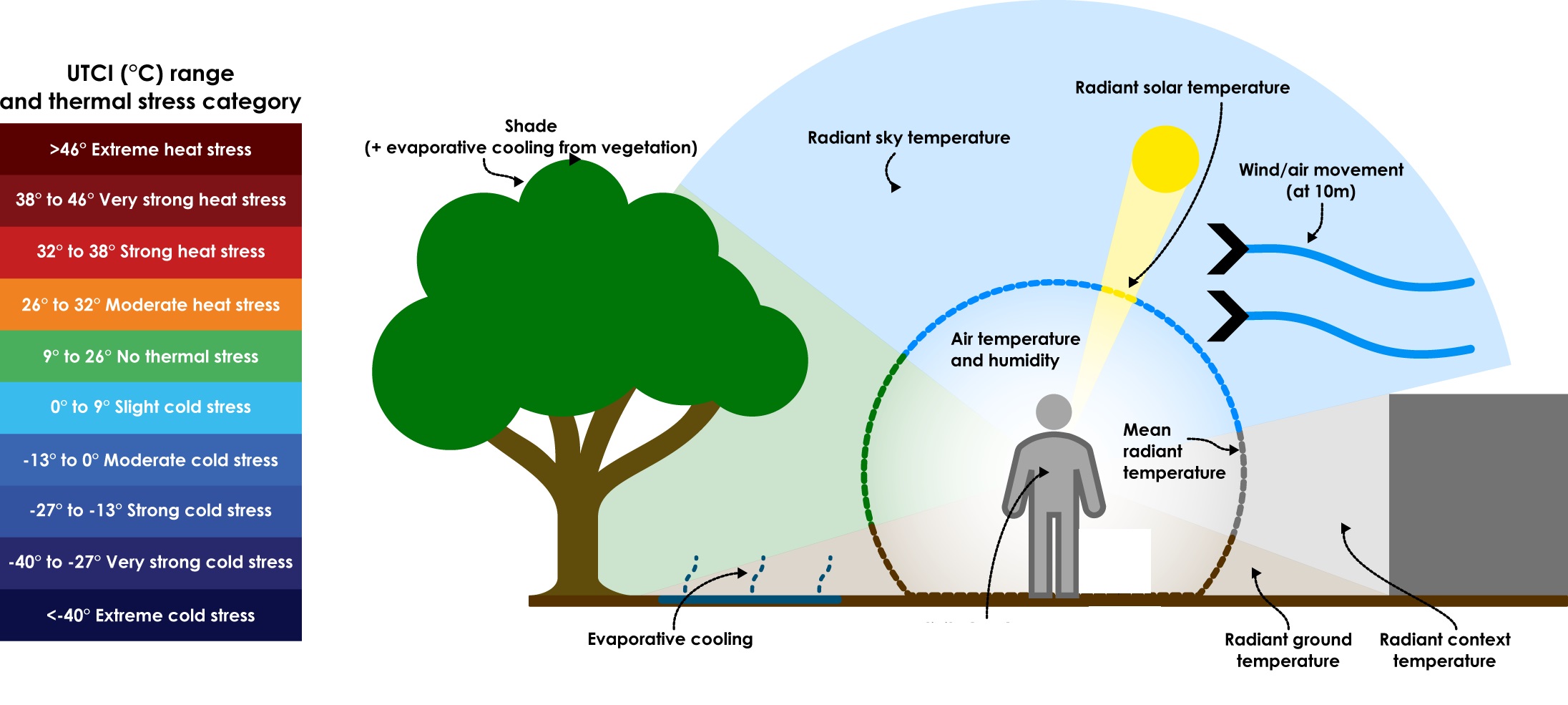

Four key factors are measured to determine thermal comfort: wind, humidity, air temperature, and radiant temperature. Together, these factors are combined into an equivalent temperature called the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI). The report lays out a target for the percentage of time that the UTCI of a public space should land in a comfortable range for the various times of year: winter, summer and the shoulder months. Anybody can use the guidelines to learn how to design with thermal comfort in mind, but only city-initiated planning and large area studies are required to measure thermal comfort. The city recommends that both large park capital projects and large-site development projects over 5 hectares also undertake a voluntary analysis.

Now, when a change to a site is proposed, the analysis provides a before-and-after comparison to determine if the proposed change meets those targets. If the design falls short, the study’s toolkit provides design recommendations to choose from to address the conditions. The toolbox provides a variety of options, from neighbourhood-scale ideas like streetscape design or the orientation and size of parks, to small-scale suggestions like the effective use of trees and vegetation for natural heat regulation. It’s a novel and flexible approach meant to avoid prescriptive form-based solutions that result in repetitive built form. The performance-based approach leaves designers a wide latitude to find creative approaches to meet the needs of the site, project, and community.

Climate change and extreme weather don’t impact all neighbourhoods equally. For example, overlaying Toronto’s tree canopy map with socio-economic data shows many lower-income neighbourhoods have less access to trees, shade, and other forms of relief. Seniors, youth, people experiencing homelessness, and communities with limited access to quality outdoor public spaces also face a greater impact from extreme weather. These new guidelines offer the means to apply an equity lens when designing for thermal comfort.

While there’s only so much design can do when the temperature is 30 degrees above or below zero, there are opportunities to significantly extend the hours of comfort, especially in those optimal shoulder seasons.

Toronto is the fastest growing city in North America with more active construction cranes in the sky than any other city by far (in 2024, Toronto had 221 active cranes – more than four times the number in second-place Los Angeles, with 50 active cranes). How we plan and build today will shape the city for the next century and beyond.

Dorsa Jalalian is a Toronto-based urbanist, working as an associate and senior urban designer at DIALOG.

Kristina Reinders works for the City of Toronto as the Urban Design Program Manager for Programs & Strategies.

Rong Yu is the Urban Design Project Manager for the City of Toronto.

Graphics by DIALOG

One comment

As per Policy 9.19 of the City’s Downtown Plan, no ‘net-new shadow’ is permissible on Nathan Phillips square between March and September. I find it funny that we need new policies to fix problems created by our old policies.