This article is published in conjunction with Spacing issue 71, which focuses on Toronto’s waterfront. The issue will be available shortly at the Spacing Store and other fine bookstores, and in subscribers’ mailboxes.

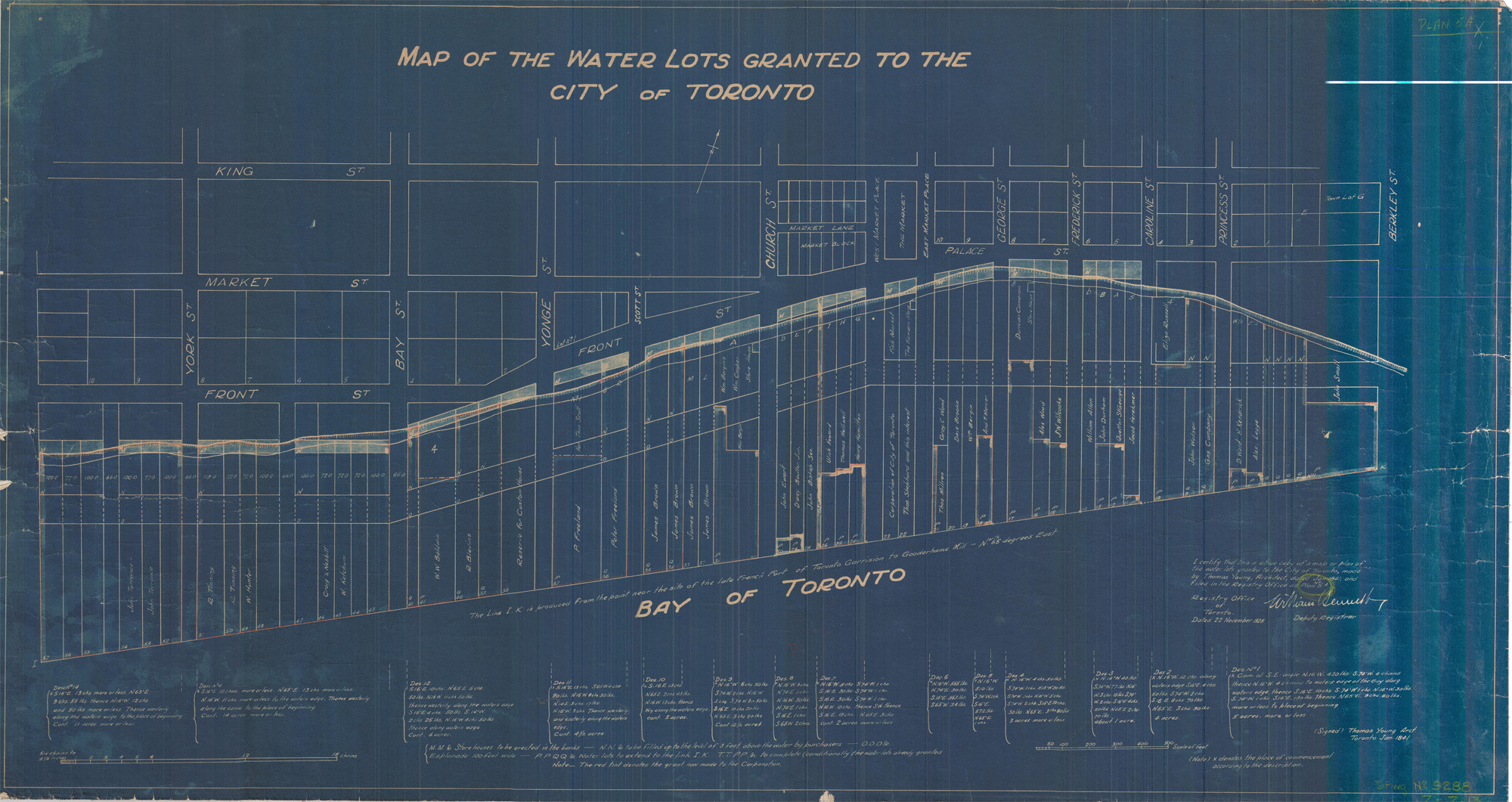

In 1841, Thomas Young — one of the first professional architects to practice in Upper Canada (Ontario) — prepared a through what is now the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood at a critical transition point in the city’s history and its relationship to the body of water to its south.

The position of the water’s edge he marked on his blueprint reflected the natural lake shoreline as it had been for millennia. Crucially, his drawing captured the position of the top of the bank and the water’s edge shortly before commercial development and expansion of the land south into the lake began in earnest.

Young showed how the land would be expanded, and who would own the dozens of prime new water lots. An extension of the existing street grid and the addition of a new east-west road, the Esplanade, was also included in his drawing.

From this moment on, the city’s practice of filling in the lake to create new commercial land would permanently obscure the location of the natural shoreline. Today the only clear visual reminder of the most recent natural shoreline is a subtle slope in the land south of Front Street.

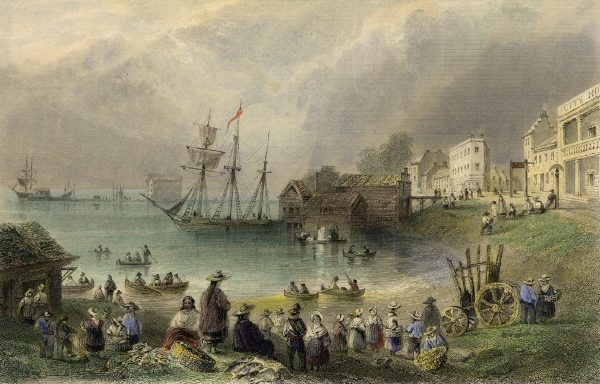

Anyone entering the natural enclosure of the Toronto Harbour before the arrival of British colonists would have been presented with a tranquil scene: calm water surrounded on almost all sides by lush plant life.

Thick rushes lined the bay’s north shore before giving way to a narrow stone beach below a grassy clay cliff that varied in height, reaching about 4 metres (13 feet) tall in places. Behind that, a dense forest.

Several small creeks tumbled into the bay on its northern edge; ahead, a river delta thick with marsh plants.

At this time, the only entrance to the harbour was at the west end, near the current site of the Island airport. An isthmus still connected the Toronto Island and the sandy marsh at the mouth of the Don River, which kept the water of the bay mostly calm.

This version of Lake Ontario near the future site of Toronto had existed for about 3,000 years. Before that, the easternmost of the Great Lakes had undergone considerable changes over its approximately 10,000 to 13,000-year history.

As the last ice age ended, the retreating Laurentide ice sheet, which once covered most of Canada and northern parts of the United States, carved out a deep basin that gradually filled with fresh water.

This version of Lake Ontario, known by geologists as Glacial Lake Iroquois, drained to the Atlantic Ocean through an outlet at its southeastern corner, through present-day Syracuse, New York. The Laurentide ice sheet still blocked what is now the St. Lawrence River valley, forcing the water to find another outlet to the sea.

Remnants of Glacial Lake Iroquois remain in Toronto — the steep ridge north of Davenport Road that overlooks downtown Toronto was a shoreline cliff at the edge of this body of water.

As the ice sheet continued to wane, the lake level began to drop, and about 10,000 years ago, in what is known as the Admiralty Lake era, the lake was smaller than it is today, with the north shore of the lake about five kilometres (3.1 miles) south of its present location.

Some of the earliest-known physical evidence of humans in the Great Lakes dates from around this time: In 1908, a team of workers digging a tunnel for water pipes near Hanlan’s Point found roughly 100 shoeprints in clay 21 metres (70 feet) below the water.

The prints indicated that people were moving north — in the direction of today’s downtown Toronto — away from the shore of a smaller version of Lake Ontario.

Continuing with their work, the workers destroyed the shoeprints shortly after they were found. The only documentation of the find was a single sketch and a few notes by Toronto city inspector W.H. Cross that were reproduced in local newspapers and then largely forgotten.

“It looked like a trail,” wrote Cross. “You could follow one man the whole way. Some footprints were on top of the others, partly obliterating them. There were footsteps of all sizes, and a single print of a child’s foot.”

Complex changes in geography over many thousands of years caused the lake to fluctuate in size. After the Glacial Lake Iroquois era, and the smaller Admiralty Lake era, the lake began to increase in size again, reaching approximately its current proportions about 3,000 years ago.

It was this version of the lake that British colonists encountered in the 18th century, and as a result the oldest surviving technical surveys with exact measures of the Toronto Harbour date from this time.

A 1792 plan of Toronto Harbour by 19-year-old Joseph Bouchette provided depth measurements and other descriptions that would be used by John Graves Simcoe during his founding of the garrison, which became Fort York a year later.

“Dense and trackless forests lined the margin of the lake and reflected their inverted images in its glassy surface,” Bouchette later recalled. On his plan, he recorded an “Indian hut” on the shore beneath “luxuriant foliage,” likely somewhere near present-day Parliament and Mill Streets, and the presence of two Mississauga families.

“The bay and neighbouring marshes were the hitherto uninvaded haunts of immense coveys of wild fowl,” Bouchette remembered. ”Indeed, they were so abundant as in some measure to annoy us during the night.”

In 1793, in addition to the fort, the town of York was established on the north shore of the bay. Though the streets were mostly planned around a strict grid system, the arc of the natural Lake Ontario shoreline gave Front Street its distinctive diagonal orientation between Bay and George Streets.

Initially, the land south of the appropriately named Front Street remained mostly free of buildings. A broad gravel walk followed the top of the cliff and provided a picturesque view of the bay. This walk gave rise to the idea that the waterfront should be preserved as a public park:

“From its agreeableness, overlooking as it did, through its whole length the Harbour and Lake, this walk gave birth to the idea, which became a fixed one in the minds of the early people of the place, that there was to be kept in perpetuity, in front of the whole town, a pleasant promenade, on which the burghers and their families should take the air and disport themselves generally,” wrote 19th-century historian Henry Scadding.

Despite these civic-minded intentions, the waterfront in the St. Lawrence area was soon developed, and by the mid-1800s the shore was lined with warehouses and wharfs.

What followed was an era of rapid expansion into the lake to accommodate new buildings, railways, and later expressways and the industrial Port Lands.

The natural shoreline Thomas Young recorded is now well inland, running generally parallel to the south side of Front Street East from Yonge Street to Parliament Street.

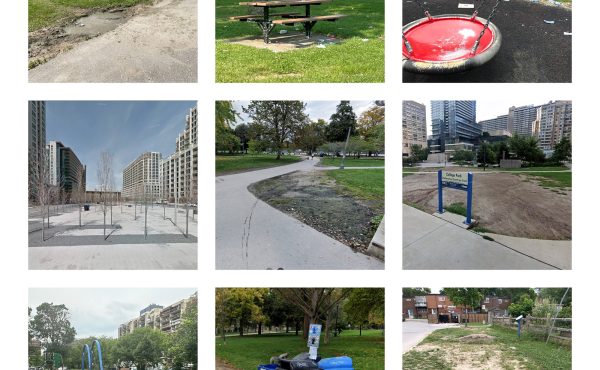

Soon, Heritage Toronto will retrace the 3,000-year-old natural shoreline of Lake Ontario as it was marked on Young’s 1841 map with guided walking tours and a series of plaques placed at the historic water’s edge on 10 streets within the St. Lawrence neighbourhood.

This is the first time Heritage Toronto will interpret such a substantial lost natural feature and the first time a linear plaque series will be used for this purpose in Toronto.

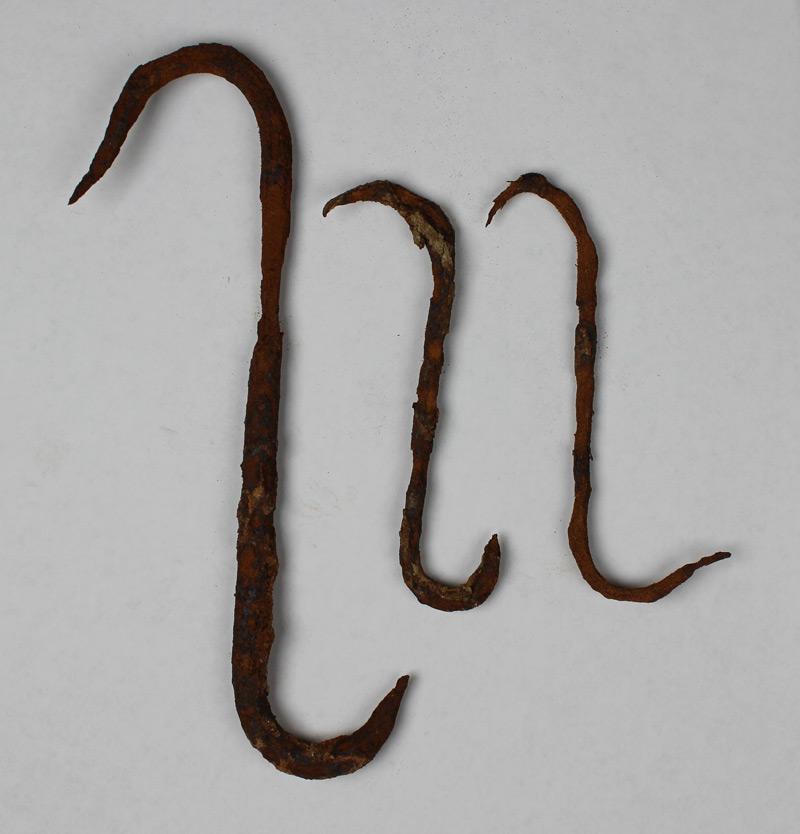

Each shoreline marker plaque will carry an image of a historical item related to the waterfront or the period — for example, pottery sherds unearthed at the First Parliament Site, or meat hooks from the St. Lawrence Market dig.

Drawing inspiration from other linear historical interpretations like Paris’ meridian line (fictionalized as the “Rose Line” in the Da Vinci Code), Toronto’s markers will carry text encouraging readers to walk the city’s vanished lakeshore.

At each end, larger interpretive plaques with more information on the ever-changing Lake Ontario shoreline.

The shoreline project is a partnership between Heritage Toronto, the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Association, and the office of Councillor Chris Moise.

By interpreting the 3,000-year-old natural lake shoreline based on Thomas’ 1841 survey markings, Heritage Toronto, with its partners, will provide a reminder of the changing shape of Toronto’s waterfront and our relationship to it.

For more information on the upcoming tours, please visit heritagetoronto.org

Chris Bateman is the manager of the Heritage Toronto plaques program.

One comment

So the cliff face by St Claire and Scarlett Rd was left over of the peninsula from the ice age as seen on the Niagara side?