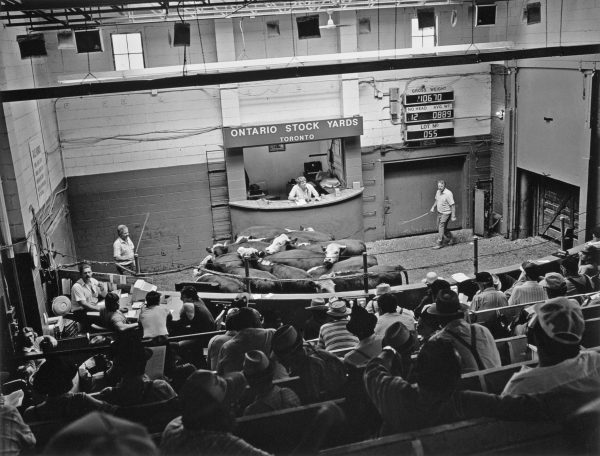

The neighbourhood designation “Stockyards District” evokes indistinct memories of what for much of the twentieth century was one of Toronto’s most concentrated zones of heavy industry. Sadly, nothing remains to mark the site of the Ontario Stockyards, originally the Union Stockyards, the hub around which the city’s meat packing industry coalesced after 1903.

The district originally included an area on both sides of St. Clair Avenue West, west of Keele Street. It included, grouped around the stockyards, an extensive rail network, three large meat packing plants and many smaller industries, all dependent on a steady supply of animals for slaughter. The area is now largely occupied by carefully planned residential streets, a shopping mall, and on the stockyards site itself, several big box retailers.

My 1991 photographic documentation of the stockyards amounted to only 17 sheets of medium format negatives and a final portfolio of 26 images, most of which are included below. I began it while I was still at work editing my major project on the Wickett and Craig Tannery, which had ended a year earlier. I knew I couldn’t afford to engage in another project of that scale, and in any case the stockyards was a less complex subject than the tannery had been.

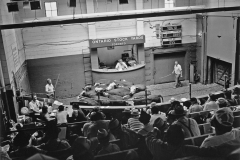

Few archival photographs of the stockyards were accessible in that era before the internet revolutionized archival research. Left to my own devices, I decided to concentrate on showing the largest possible range of architectural spaces inside the complex. While photographing at Wickett and Craig, I had become inured to extremely strong odours, so I knew I wouldn’t be bothered by the barnyard smells I would encounter.

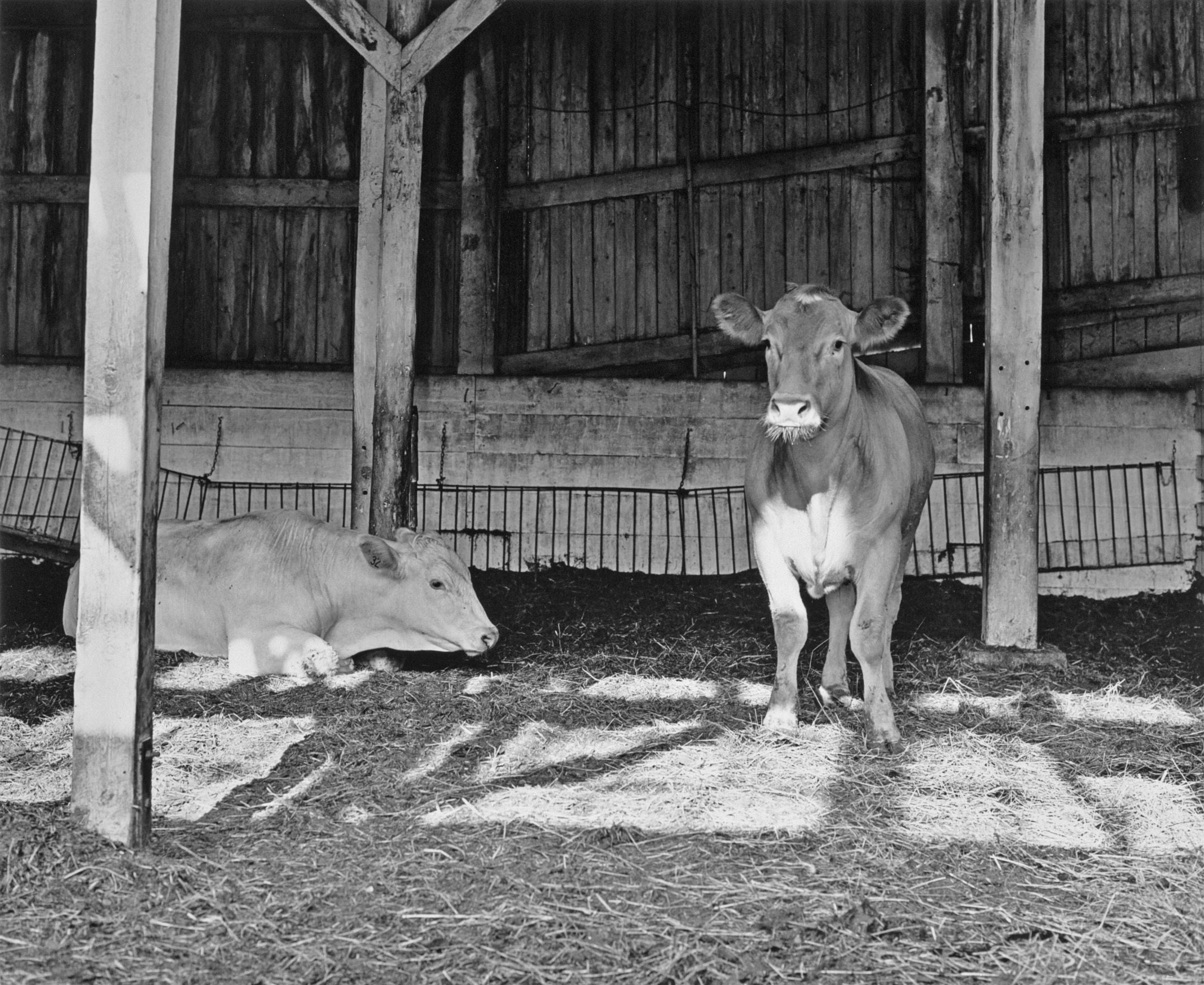

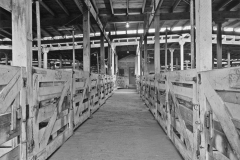

Looking closely at my photos today, I remember how the different structures in what might have been the oldest part of the complex shaded into each other as I walked through them. In this area, the roofs were supported by wooden poles made from thin tree trunks, with bevelled timber blocks serving as capitals. The lighting was soft and even, but often quite dim, making the use of a tripod mandatory.

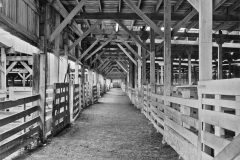

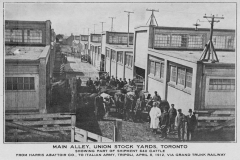

After a fire had destroyed much of the complex in 1908, ten identical stables were built in two rows that faced each other across a central alley They had all survived intact but were in a dilapidated state. The end gables of these buildings were in concrete, but along their sides the concrete walls only came up to shoulder level, supporting the wooden structure above. The roofs rested on squared timber columns and beams with Y-frame bracing.

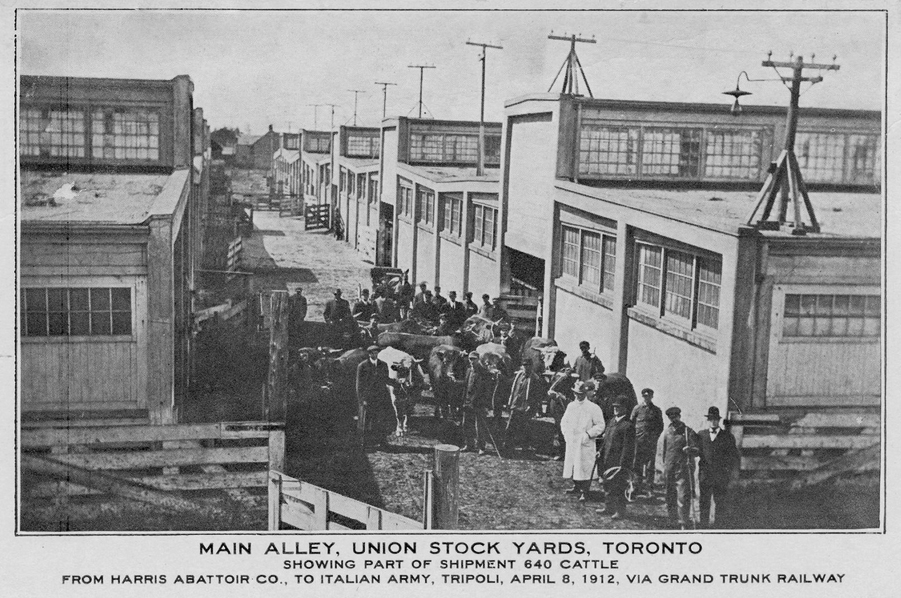

An extraordinary photo from 1912 shows what these sheds looked like when they were new. Natural light entered through strip windows, supplemented by roof monitors that ran the full length of each shed. While some of the windows had since been boarded up, these buildings were still filled with natural light.

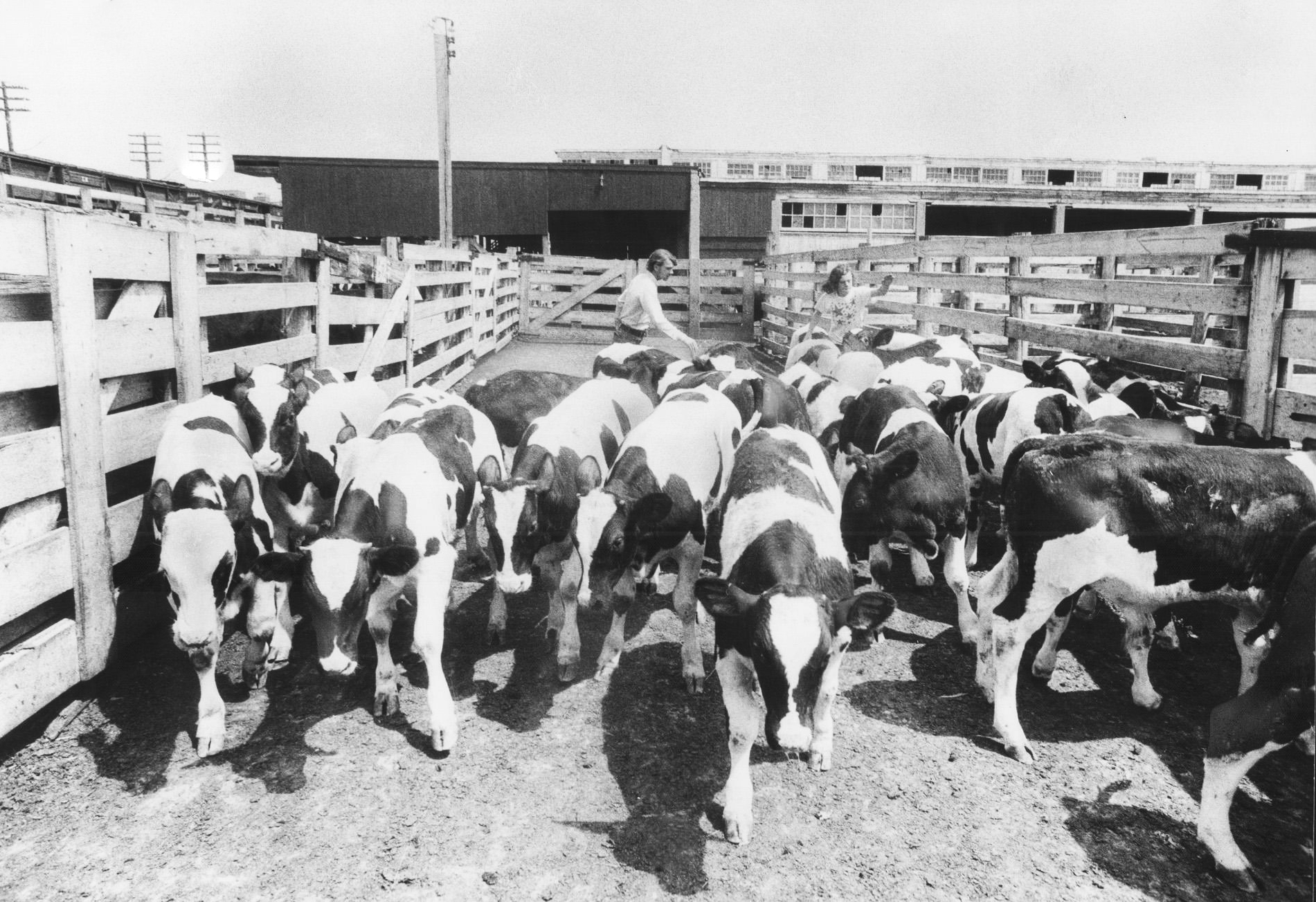

The shelter these buildings provided for the penned animals contrasted with conditions at the notorious Union Stockyards in Chicago, where all the pens were left exposed to the elements. There was, however a small section of open-air holding pens at the west end of the Toronto site. While no archival photos taken inside the stables have come to light, professional views of these outdoor pens were taken at various times, usually when they were empty during labour disruptions.

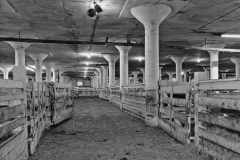

At some point between 1924 and 1947, a large stable of a novel type was added to the southeast quadrant of the site. Unmistakably the work of an architect, its design reflects the Modernist sensibility that was pervasive in Toronto during that era. It was a two-storey structure of reinforced concrete with grid of oversized mushroom columns at ground level. The upper floor, which I was unable to enter, had similar ribbon windows and roof monitors to those of its neighbours.

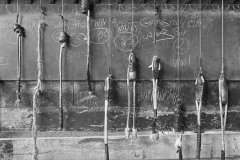

I was concerned about not allowing my relatively objective view of the stockyards to descend into nostalgia. Thus during several visits in July and August, 1991, I avoided the temptation to take details of timeworn functional objects such as wrought iron gate hooks and strap hinges.

The one exception was a view I took of a panel consisting of a blackboard behind a row of numbered pull cords, whose purpose I no longer remember. Judging from another photo I took in the same area, it seems to have been part of a mechanism for remotely opening the doors of holding pens by means of cables, pulleys and levers.

I was surprised to learn recently that although the Ontario Stockyards moved to Cooksville, Ontario in 1993, Toronto’s meat packing industry is still active in the Stockyards District, providing much-needed local employment. Some new homeowners express concerns about the odours emanating from the remaining slaughtering and processing plants.

Thus, although there is no physical monument to the vanished stockyards in the Stockyards District, there could be said to be an olfactory one.

All photos copyright Peter MacCallum unless otherwise indicated.

STOCKYARDS PHOTO GALLERY

One comment

Impressive photos and article! The Stockyards’ history is fascinating. Thank you for going out to photograph them before they were redeveloped. It’s a shame that the city dropped the ball on commemorating its rich history and guiding its redevelopment to something better than mere suburban-style big box plazas. There should have been some preservation and adaptive reuse of the built form. I don’t believe there’s a single historical plaque. Imagine the brick walkways between the pens reused between new buildings or in a local park.

Apparently, an Edwardian arch from the Gunns Abattoir/Canada Packers complex was preserved but put in storage and never installed anywhere. I heard that city officials don’t know where it is anymore. It could have made for a nice folly at the TTC’s Gunns Loop or in Maple Claire Park.

The big box stores that replaced the Stockyards aren’t walkable or pedestrian friendly, lack architectural quality, and have giant surface parking lots that are often bigger than the stores themselves. They generate a lot of vehicular traffic because they rely on shoppers to drive. Their massive parking lots contribute to the urban heat island effect, overwhelm stormwater infrastructure during storms, and generate a lot of litter that blows onto the streets and in people’s yards.

Unlike the small retailers in the Junction BIA, the big stores like the Home Depot, Canadian Tire, Rona, and Walmart in the Stockyards don’t seem to care about the cleanliness of the public realm around their stores. Ornamental bushes on the edges of their properties are often caked in litter. Rona has a historic roundhouse turntable on their property that they’ve allowed to crumble and fall apart. I’ve never seen them advocate for public realm improvements or organize a street festival.

The Stockyards’ redevelopment is also an indictment of the overly restrictive “employment lands” zoning. There was no more interest in building large-scale slaughterhouses or industry in general in the Stockyards when the Ontario Stockyards and Canada Packers closed. The area’s advantage was being close to both CN and CP’s mainlines (which intersect at the Junction neighbourhood). That was no longer an advantage by the late 20th century, when industry wanted locations near major highways.

Unlike in Liberty Village, mixed-use projects were not allowed. So the only thing that got built in the 1990s and early 2000s were these regrettable big box plazas with massive parking lots (and a couple of subdivisions on the edges of the area).

Fortunately, the tides turned a bit with the preservation and adaptive reuse of the Symes Road Incinerator, a beautiful Art Deco landmark that dates back to the Stockyards’ industrial era. Marlin Spring built a respectable mixed-use condo building in the area called Stockyards District. There are now craft breweries and some artist studios. There’s a mixed-use Avenues plan for St. Clair Avenue West. Things are headed in the right direction. But more work needs to be done to preserve and commemorate the area’s past. For that reason, this article was very enjoyable!