The north portion of St. Lawrence Market is arguably the second most historic spot in the post-colonial city, after Fort York.

A public market has been operating there continuously since 1803, which is quite extraordinary. Front Street at the time was actually the front of the Town of York, as Lake Ontario lapped up at the south side. Over many generations, Toronto grew around the north market, and the complex itself evolved, through several increasingly elaborate iterations and various ancillary uses (e.g., the municipal offices once occupied a vacant granary space on the second floor). For several decades, an arched connection linked it to what became the south market, and streetcars passed underneath.

In the late 1960s, the city demolished the north market and replaced it with a shabby low-rise structure, which didn’t seem at all out of place amidst the expanse of post-demolition parking lots that covered the east end of downtown.

Then, in 2002, council decided to rebuild the north market, and the staff reports from those heady times all begin with a generous description of the site’s rich civic past. But over time, the staff reports stopped citing the history and instead focused on more prosaic matters, such as parking and the court-services office space meant to live on the upper floors.

In 2016, after the 1968 building had been demolished, archaeologists working on the site unearthed an extensive covered drain, which had been used by the butchers who occupied the north market. That drain told lots of stories, but Mayor John Tory was too scared to use public funds ($2 million) to have it preserved and displayed. Eventually, city staff and their consultants edited all but a little segment out of the project, and then somehow forgot to include any kind of heritage commemoration — so many photos, so many stories — in the final plan for the ground floor market space.

This sorry episode demonstrates not just how Toronto forgets its past, but also how the city manages to forget how it forgets its past.

I visited the north market, which opened officially in April, for the first time a few weeks ago. In 2016, I’d stood down in a hole next to that drain for a story. The consulting archaeologists told me the tale of a building, and an address, that goes some distance in explaining who are as a city.

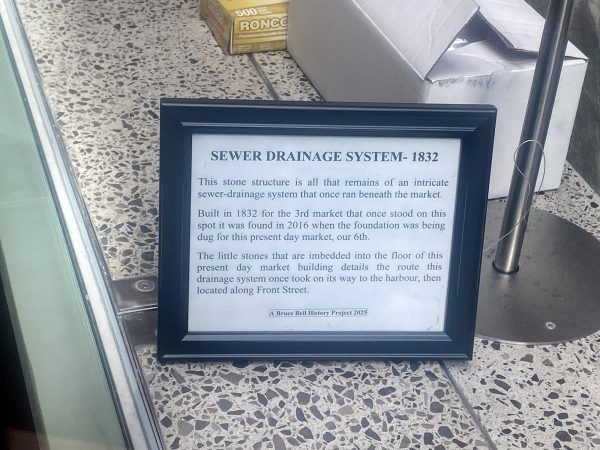

The drain fragment that survived the subsequent value engineering is contained in a sunken viewing box about the size of a parking space, situated near the back of the hall. It sits under highly reflective glass, which makes the drain difficult to see, and is back lit with a vaguely creepy yellow-ish light, for reasons that surpass comprehension.

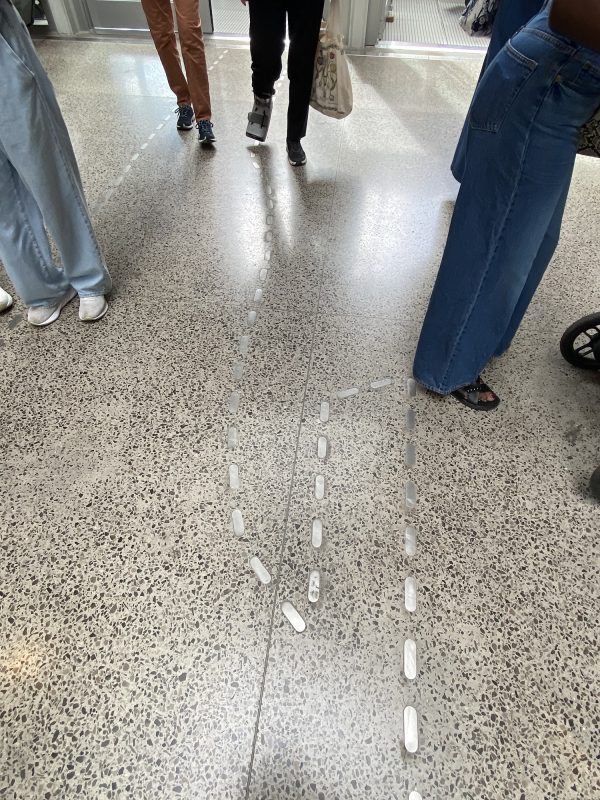

A small cheaply framed sign the size of a sheet of paper is propped up next to the drain, with the title, “Sewer Drainage System — 1832.” In two short paragraphs, it explains what you’re looking at, and then points out that the “little stones embedded into the floor of the present-day market building details the route this drainage system once took on its way to the harbour…” The sign is signed, “A Bruce Bell History Project, 2025.” It’s not even from the city.

(“Additional heritage features are currently being developed,” according to a spokesperson, “and the City of Toronto will continue to keep the public informed as new updates become available.” There are no further details, however, which is remarkable at this late date.)

I guess it’s worth mentioning that way back in 2004, a large working committee tasked with coming up with a plan — City staff plus people from various local groups — agreed on how “heritage/architectural compatibility could be achieved on the site.” A decade later, the city itemized a range of “benefits” associated with redeveloping the north market, including “improvement of a city landmark and tourist destination” and “[improving] compatibility with the heritage character of other buildings in the Market complex and in the Market area.”

And yet.

The market “complex” is unquestionably one of Toronto’s top tourist destinations, but visitors to the new north market would have no clue about its fascinating and deep connection to the city’s past. Nor would Torontonians not steeped in the area’s heritage, which includes the thousands of school children who get taken to the market on field trips. Lots of stalls, and all the liveliness of a farmer’s market, but if you want to know more, you’re just out of luck.

I get that all the city officials, consultants, and contractors who worked on this absurdly protracted project had other design fish to fry. It’s a big, expensive building with multiple mandates that’s been shoe-horned onto a tight parcel of land. And I also understand that Toronto is faced with far more pressing and dire problems.

Still, it’s astonishing to me that no one involved in a 23-year project managed to keep their eye on this ball, and not just to mollify the small clique of Muddy York aficionados. In this day and age, is it a secret that tourists, international and domestic, seek out historic architecture and heritage sites when they travel? Every self-respecting destination marketing official gets the connection. Indeed, you don’t need to be a seasoned world-traveller to recognize that cities with history make an effort to surface and celebrate their pasts in order to enliven the sense of place in older districts.

But a visitor to the new north market today would have no idea what stood there before (five separate structures) nor how all that deep history connects to the present of a city that has a genuinely interesting story to tell about foodways.

Local officials tasked with managing the north market and Toronto’s heritage more generally need to remedy this bizarre attack of civic amnesia, and do so in a way that goes beyond our once-over-lightly approach to such things.

First, however, the city should admit that it forgot to remember, and we can go from there.

top photo by Jacob Côté Photography/ERA Architects; middle photos by John Lorinc