EDITOR’S NOTE: The University of Toronto’s School of Cities will be screening a re-mastered print of the film, “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, provided by NYC’s Project for Public Spaces, on Tuesday at 6pm. Find out more details on the event’s page.

In the 1960s and 1970s, New York City’s planning board began cutting a certain type of deal with Manhattan developers, offering additional height and density in exchange for more open space at grade, typically in the form of plazas or walkways between buildings and blocks.

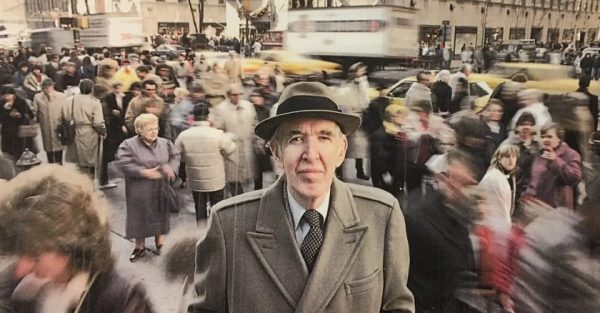

Known as “privately-owned public spaces” (POPS), these became the subject of intensive sociological scrutiny by an urbanist-author named William (“Holly”) Whyte. In the late 1970s, he and some collaborators fanned out across Manhattan and set to work filming and documenting the way New Yorkers used these spaces, as well as the sidewalks abutting them — how they behave, how they interact, when and why they gravitate to certain POPS and not others.

“People tend to sit where there are places to sit,” observed Whyte after completing his study. That aphorism serves as something of a unified field theory of public space and has launched countless street life studies on seating in parks, plazas and other city spaces.

Whyte published the results in a short book and turned the footage into a film, “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces.” The University of Toronto’s School of Cities will be screening a re-mastered print, provided by NYC’s Project for Public Spaces, tomorrow at 6pm (details here), followed by a panel discussion with Ilana Altman (Bentway), Jen Angel (Brickworks), Fadi Masoud (U of T Centre for Landscape Research) and Jason Thorne (City of Toronto).

By the time he turned his attention to Manhattan’s public spaces, Whyte was a nationally prominent figure whose meandering career straddled journalism, consulting and urban planning.

Born in 1917 in a small town near Philadelphia, he went to Princeton, served in the Marines during World War II, and eventually landed at Fortune, then published by the Time magazine empire, where he spent years as a high-profile writer, author and editor.

Whyte is credited with spotting the journalism of a young freelancer named Jane Jacobs, a contributor to another Time publication, Architectural Forum. He eventually published Jacobs’ early critiques of urban planning orthodoxies in an anthology. Whyte also connected her to his contacts at the Rockefeller Foundation, which provided Jacobs with a $10,000 grant to let her take the time to research and write what would become The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

He arrived at urbanism by a circuitous route. According to Richard K. Rein’s 2022 biography, American Urbanist, Whyte’s experience in the Marines, where he worked in communications and strategy, sparked his interest in the nature and dynamics of organizations, both rigidly hierarchical ones as well as those that found ways to incorporate the views of iconoclasts and outsiders. Whyte published The Organization Man in 1956, which turned him into a sought-after thought leader on the subject of corporate behaviour.

Living in New York, he talked frequently to the city’s largest corporate employers, whose executives and managers lived in the rapidly growing post-war suburbs, commuted into Manhattan, and often found themselves in those plazas or on sidewalks, trading gossip or watching the world go by. Where Jacobs described the `ballet of the sidewalk’ outside her west Village apartment, Whyte noted the adjacent phenomena: that when friends or co-workers encounter one another on sidewalks or walkways (or at least those in Manhattan), they often end up stopping to talk right in the middle of the flow of traffic.

Intellectually restless, Whyte became fascinated by the suburbs, but also practiced what today would be described as enthusiastic and aggressive NIMBYism. He advised community groups and exurban municipalities how they can block subdivision developers that were seen to be scarfing down the American landscape. Yet this was the era of Rachel Carson’s The Silent Spring and the beginning of the Earth Day movement, and Whyte’s views reflected the temper of the times.

During his years as a business journalist, he was be-friended by Laurence Rockefeller, brother of New York State governor Nelson, and a scion of their grandfather’s oil empire. Rockefeller hired Whyte, who had set himself up as a consultant, to write reports on urban sprawl, compact development (which he dubbed “cluster housing”) and conservation. Some of those reports, according to Rein’s biography, played a role in informing the nascent environmental policies of presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon.

By 1969, he’d become curious about public space, and in particular New York’s drab concrete plazas. The following year, Whyte set up a think tank, the Street Life Project, with the goal of using empirical observation to figure out why some public spaces worked and other didn’t. The results turned into the book and the film, and also found their way into the city’s zoning codes.

Among other things, Whyte spent a lot of time assessing how and why people sit in public spaces. His insights about the social role of moveable street furniture, and how such seemingly simple amenities can animate urban space, were transformational. They are now deeply embedded in New York’s approach to public space, and Whyte’s influence can be found in many other global cities, promulgated by disciples like the Danish planner Jan Gehl.

Yet his influence, for some strange reason, doesn’t really extend into Toronto’s public spaces and our ever-expanding network of POPS, most of which are found downtown in the vicinity of high-density developments. The provision and siting of seating in our parks and public spaces tends to be stingy and often peculiar. While there are exceptions — e.g., Love Park — most seating-oriented street furniture is bolted to the ground or chained to trees.

Also, again with exceptions, the designs of many Toronto POPS focus more on landscaping and pathways than on seating, either fixed and moveable. These places tend to be liminal, serving as grade-level decoration for a condo or an office building. Lingering is not just discouraged, but often not possible. And let’s not get started on hostile design or coffee carts… (As Whyte wrote in the book version of The Social Life, “If you want to seed a place with activity, put out food.”)

There are landscape architects — the late Claude Cormier being the most notable — who understood how to create public spaces in Toronto that not only invited the public to hang out, but also succeeded in that objective.

Too many other spaces are either featureless, per Parks Department guidelines, or over-thought — seeking to cater to multiple (imagined) user groups without fully recognizing their role in urban space, or acknowledging the psychic damage inflicted on Toronto’s civic life by discouraging city-dwellers from spending time in their public places. Surely, we’re mature enough as a city to stop the practice, barely recognized in official policies, of cheaping out on street furniture simply to prevent homeless people from sleeping in parks.

The film taught a generation of designers and planners about the importance of working backwards: you begin by closely watching how a successful public space actually functions, and then reverse engineer it to understand the elements required to replicate its popularity.

There’s a footnote here: Whyte himself came to recognize, through his later work with smaller communities or sprawling cities like Dallas, that density is the foundational ingredient — the onions that you braise first, before adding anything else.

Toronto now has lots of density in its core area, and certainly enough examples of urban-minded public spaces to determine which ones work and which ones don’t — and why. The evidence is there for the taking, and should (with the benefit of Whyte’s insights) be quite sufficient for injecting more social life in Toronto’s small urban spaces and parks.

3 comments

https://spacing.ca/national/2023/02/21/book-review-american-urbanist/

One of the challenges of the conversation about public space activation, pop-ups, social life of small spaces, things like putting chairs in Times Square etc is that it is very NYC-focused and centred on places where the densities are such that if you build it, they will come. It’s much harder in locations where the density isn’t there to become more friendly, interesting, and conducive to social life. That’s not to take away from those achievements and the importance of density in considering where to allocate scarce programming resources; more just a call for additional nuance, thinking, examples, strategy, etc on how to improve places that don’t have thousands of people nearby just looking for a place to sit.

Whyte’s work reminds us that successful public spaces aren’t accidental they’re carefully observed and human-centered. The connection drawn between POPS in Manhattan and Toronto’s urban fabric is especially insightful.