In today’s NY Times magazine they look at 74 ideas that were talked about over the past year. Some are weird — like the comb that listens and the N.C.A.A. Psyop — but there are a few that have a particularly urban element to them, including (click on links for full text):

In September, Bangkok witnessed the opening of the Suvarnabhumi Airport, which when finally completed will include virtually all the components of a major metropolis: shopping malls, office buildings, hotels, hospitals, an international business center, conference and exhibition spaces, warehouses and even a residential community. Traditionally, of course, airports have served cities, but in the past few years airports have started to become cities unto themselves, giving rise to a new urban form: the aerotropolis.

In September, Bangkok witnessed the opening of the Suvarnabhumi Airport, which when finally completed will include virtually all the components of a major metropolis: shopping malls, office buildings, hotels, hospitals, an international business center, conference and exhibition spaces, warehouses and even a residential community. Traditionally, of course, airports have served cities, but in the past few years airports have started to become cities unto themselves, giving rise to a new urban form: the aerotropolis.

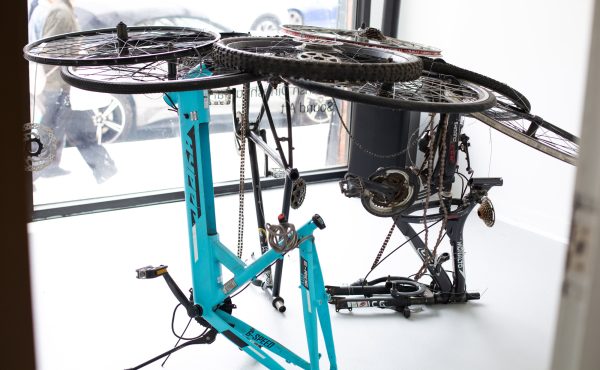

Bicycle Helmets Put You At Risk

For years, cyclists who ride on city streets have cherished an unusual superstition: if they wear a helmet, they are more likely to get hit by a car. “I belong to an e-mail list for cyclists, and they complain about this all the time,†says Ian Walker, a psychologist at the University of Bath who rides his bike to work every day. But could this actually be true?

Walker decided to find out — putting his own neck on the line. He rigged his bicycle with an ultrasonic sensor that could detect how close each car was that passed him. Then he hit the roads, alternately riding with a helmet and without for two months, until he had been passed by 2,500 cars. Examining the data, he found that when he wore his helmet, motorists passed by 8.5 centimeters (3.35 inches) closer than when his head was bare. He had increased his risk of an accident by donning safety gear.

“Make no little plans,†the architect and urban planner Daniel Burnham wrote a century ago, “they have no magic to stir men’s blood.†For the last four decades, however, little plans have been the signature creations of the American city. Ever since 1964, when Robert Moses, New York’s master builder, was prevented from blasting a freeway through SoHo, the most successful urban-design strategies undertaken by large American cities have been essentially conservative. Jane Jacobs’s crusade against architectural master plans, combined with a growing historic-preservation movement and the fall of heroic high modernism, led to a generation of planners, architects and activists intent on restoring, rather than drastically reshaping, the urban fabric.

But now cities are once again planning with grandiosity. This year witnessed the return of what you might call big urbanism, with large-scale redevelopment projects sprouting nationwide….

The British artist Paul Curtis is not sure what to call his version of vandalism. “People call it ‘reverse graffiti,’ †he says, “but I prefer something less sinister: ‘clean tagging’ or ‘grime writing.’ †Curtis, a k a Moose, selectively scrubs dirty, derelict city property (tunnel walls, sidewalks) so that words and images are formed by the cleaned bits. “It’s refacing,†he says, “not defacing. Just restoring a surface to its original state. It’s very temporary. It glows and it twinkles, and then it fades away.â€

The British artist Paul Curtis is not sure what to call his version of vandalism. “People call it ‘reverse graffiti,’ †he says, “but I prefer something less sinister: ‘clean tagging’ or ‘grime writing.’ †Curtis, a k a Moose, selectively scrubs dirty, derelict city property (tunnel walls, sidewalks) so that words and images are formed by the cleaned bits. “It’s refacing,†he says, “not defacing. Just restoring a surface to its original state. It’s very temporary. It glows and it twinkles, and then it fades away.â€

To pay for industrial scrubbers, he has sold some of his reverse graffiti as advertising. But mostly he sticks to his own art. Critics, like the City Council in Leeds, have accused him of breaking the law, but for what? Cleaning without a permit? “Once you do this,†he says, “you make people confront whether or not they like people cleaning walls or if they really have a problem with personal expression.â€

Also check this Spacing Wire post on reverse grafitti.

Public art projects are usually intended to beautify. But artwork commissioned this summer by the city of Cambridge, Mass., has a more utilitarian goal: reducing traffic speeds at a busy intersection.

The junction in question is in residential West Cambridge (at Walden Street and Vassal Lane); 6,000 cars pass through it every weekday. “People were asking, ‘Isn’t there something you can do?’ †says Susanne Rasmussen of the Cambridge community-development department. Rasmussen and her colleagues were aware that neighborhood street murals in Portland, Ore., had had the unintended consequence of slowing drivers down, and they decided to experiment. Soon the city was taking proposals for a circular mural, 20 feet in diameter, to be painted on the asphalt in the center of the intersection — a kind of artwork rotary. The objective, to reduce average speeds from 30 miles per hour to 25, seems relatively modest, but Rasmussen, citing statistics, says it’s significant: “The chance that a pedestrian would survive an accident is vastly greater at that speed.â€

One comment

What? An urban form beside an airport? Heresy! Where’s Bangkok’s CommunityAIR?