Before the holidays I got into a discussion with Ed Keenan about whether there is a difference between a fee and a tax. In an article, Keenan said “a user fee is actually another kind of tax the government collects to pay for the services it provides—it’s a tax levied on a specific activity.” This point of view was based on discussion by US commentators mostly relating to the US federal budget.

In the context of an Ontario municipal government, however, a fee and a tax are in fact conceptually different, and that difference goes to the heart of the excellent points Keenan makes in his article.

For an Ontario municipal government, a user fee can only be charged in exchange for a specific service offered to the person paying the fee. Importantly, the city is not allowed to charge more in a fee than it costs to provide the service. There’s some wiggle room, of course — the city can be generous in its estimate of what the service costs — but there is nonetheless a limit. Fees don’t give the City any extra funds to cover other unrelated expenses. Nor can the City charge one person a fee for a service it provides to someone else.

A tax, by contrast, is a contribution to a collective pool of money that we, the voters, through our elected representatives, can spend however we wish. It doesn’t have to be for a service — we can send money for typhoon relief in the Philippines, if we want. Or we can pay for services for other people, that we could never benefit from ourselves — for example, as established citizens we can choose to spend money to help new immigrants settle into our city.

Most importantly, we can use taxes to redistribute income from the wealthiest to the poorest in our society, directly and indirectly. We can’t do that to any significant extent with user fees. In fact, user fees can be make income inequality worse — they can charge the same to the poor as to the wealthy for an essential or important service.

A good example of the policy implications of the difference between taxes and fees at the municipal level lies in recreational services. In the old City of Toronto, these were provided for free, so that anyone could benefit from them. Since the wealthy pay higher taxes (more or less, since property taxes are only partially redistributive) they helped to subsidize these services so that the poor could benefit equally.

The amalgamated City, by contrast, has moved towards a user fee model for recreational services that was common in the suburban municipalities. That means that people have to pay to receive the service — making it less accessible to the poor. There are ways to get around this barrier, such as providing free services in poor areas, or to people who demonstrate they are low income in some way (both of which the City does) — but such measures always miss someone, whether working poor who don’t quite meet the low income threshold, or poor people living in a mostly wealthy area. On the other hand, people who don’t use municipal recreational services pay less in tax because they are no longer covering the costs of services they don’t use.

(There can be problems with free tax-based services too. If not enough service is provided to meet demand, it may be that people with more influence can get better access. Or, like roads, the service may get overwhelmed. Or, if the service is in fact used mostly by middle-class people, it may not really be redistributive at all.)

Whichever model you prefer, the conceptual difference between taxes and fees makes a significant difference in how the service is provided and who has access to it.

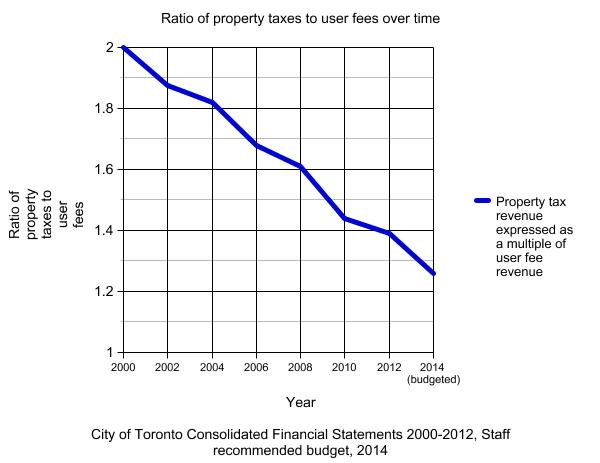

As Keenan demonstrates, this shift from taxes to fees had been a general trend in the City of Toronto’s revenue since amalgamation. The ratio of tax revenue has dropped from roughly two times fee revenue in 2000 to only roughly 1.2 times fee revenue in 2014.

Source: The Grid

It’s true that fees can be used to indirectly increase the amount of tax revenue available to the city government. For example, Toronto has moved its water services and capital spending from being paid for in part by taxes to being paid entirely by increased fees. It didn’t reduce its taxes at the same time, so in effect a lot of imminent capital spending that would have come out of taxes is now coming out of fees. That leaves more room in the capital budget for other tax-based priorities (such as new transit vehicles). A similar shift happened with garbage services (an example Keenan cites in his longer blog post on the subject).

Some services are based on a mix of fees and tax money, often a recognition that they have some redistributive impact. Transit is a good example — fees (fares) cover most of the cost, but some operations and a lot of capital funding is paid for out of taxes. This balance recognizes that low-income people disproportionately use transit. (It also recognizes that the alternative, roads, are themselves subsidized). In Toronto, however, the tax portion of transit operations funding is lower than in any other city in North America.

Fees are appealing to cities because they are much easier to sell to the electorate. Everyone can understand that if a service costs a certain amount to provide, they need to pay enough fees to cover the costs in order to receive the service. So, in the current environment where there is a strong anti-tax feeling, a city that needs more revenue to cover its growing expenses can appear to keep taxes under control by raising fees instead.

While this may free up more tax funds in the short term, in the long term shifting more and more municipal revenue from taxes to fees means that the room the City has to engage in redistribution of income becomes progressively smaller. The City becomes more and more a provider of services to those who can afford it — at the same time, making it harder for lower-income people to move up in the world because fees cut disproportionately into their resources, or they cannot afford to take advantage of services. It becomes less and less a government that strives to help balance and correct economic imbalances and enable those at the bottom of the economic ladder to move up. So the conceptual difference between fees and taxes at the municipal level has significant policy implications for the city government.

Photo by Sean Marshall

11 comments

Fees are more “sellable” to voters. A fee for a service you do not use does not interest you, but a tax to cover that same service does. The real debate comes in when it is time to decide what should have a fee and what should be covered by taxes. Then there is the hybrid: services covered by both taxes and fees.

Don: the fact that it’s more sellable to voters is part of the problem of taxes vs. fees: there is evidence that shows lower income families tend to vote less than higher income (those than can afford fees or have other options than the services provided by the City).

One thing to comsider is for what activities are you charging fees?

You could have a situation where you would charge fees for advanced swimming lessons (to cover the cost of the instructor) but have free recreational swimming

Of course this does not help if you never learned to swim in the first place.

In the pre-amalgamation days I think that Etobicoke had a program run in conjunction with the school board that provided basic swim lessons to students at a certain grade level.

Dylan, the report you linked to regarding the subsidization of roads is misleading. That report is for the US where the average fuel tax (combined federal and state) is 13 cents per liter. Here in Ontario the average is 37.5 per liter.

Glen – a fair point. I believe there are some similar studies for Canada – I should have found those.

There was an older study out of Minneapolis/Inst for Self-Reliance indicating that if cars had user fees for all the costs, property taxes there could dip by c. 40%. Here we are keen to charge kids etc. for all sorts of things so the cars/users can keep entitlements.

Commercial and industrial properties also pay property taxes. Of course, there would be no user fees that, for example, a shopping mall to pay for that it does not use. A shopping mall would not pay for a user fee for recreation, for example. A label printing company would not want its property taxes to pay for a library, since it would not use it.

However, if those commercial and industrial properties did pay through their property taxes, it would be only a small portion since it would be spread out across more payers.

I happen to work in the demerged city of Westmount, where my company pays property taxes to support a lovely set of municipal recreation facilities. As a result, employees get access to the library, courses, free swim and skate times as if we were residents.

Interesting post. Although you do take care to acknowledge opposing arguments, I think you’re overestimating the regressivity of user fees as a revenue tool. Some points worth considering were raised by a BC-based economist in her blog here: http://deadfortaxreasons.wordpress.com/2013/12/13/but-its-regressive/

Alessandro – thanks for that interesting link.

A couple of points:

– Re. her argument #2, that poor people can reduce their consumption of a service – that can still be regressive – e.g. if poor people stop using recreational facilities, that deprives them of a service that may have a negative impact on their quality of life and even future outcomes.

– My core point is not so much about fees being regressive, but about fees reducing the scope for a government to redistribute income. Even if fees are managed so they’re not regressive (don’t have a negative impact), shifting strongly to fees reduces the ability of a government to redistribute (to have a positive impact on income inequality).

I certainly support fees in some cases (e.g. water fees, which have helped reduce wasteful consumption and ensure sufficient investment), the question is the impact of changing the balance between fee and tax revenue.

I tend to agree with Keenan that governments fees are just taxes by another name. It gets more confusing when you charge HST on a city “fee”.

If there was direct correlation of new user fee resulting in a reduction of property tax I wouldn’t mind it at all. But all cases the city just adds a new user fee to a service that was covered by property tax, yet property tax remains the same.

An example would be the Water/Sewage and Garbage removal user fee that use to be covered by property taxes.