Five weeks ago, I wrote the first installment of this saga which I described at the time as a “shocking tale of procedural inertia, bureaucratic confusion, and a broken democracy.”

I have some updates to share on this story, updates that provide a glimmer of hope while at the same time illustrating how deep the systemic problems at City Hall are.

I’ll get the good news out of the way first: The city’s Sign Unit has agreed to “re-open the investigation” into these signs. City staff are actively exploring whether the billboards are legal or not, and they are helping guide me through the entire process.

Now, the bad news:

1) The “New Information”.

In the first post, I talked about how the city had originally asked the billboard company to remove the signs in 2006, but then later reversed their position based on “new information”. I have formally asked City Staff to explain what the “new information” is but sadly, I have been told that the information is simply not available. I think it’s stunning that during an era of increasing awareness about open data and government transparency, these billboard companies are still able to operate behind a veil of secrecy. The signs affect public space, they are regulated by municipal code, and staff have admitted – on multiple occasions – that these billboards do not seem to have any permits. I can’t imagine why the “new information” shouldn’t be accessible to the public.

2) Prehistoric claims.

While I have not been told officially what the “new information” is, I’ve been able to piece together my own theory, based on suggestions from a few people. Here’s how it works: The City tells a billboard company that they have an illegal sign, and that it needs to be removed. The company’s response goes something like this: “This sign has been here for over a hundred years, since before bylaws even existed. Therefore, it was a legal sign at the time of construction, and you have to let us keep it. Otherwise, we’ll sue you.” These threats seem to be quite effective, since their validity is hard to prove.

So what can we do, as public space advocates, to counter these tactics? The answer is simple: we need to prove that the signs are actually younger than the city is being told. So here’s what I’ve done for this particular location:

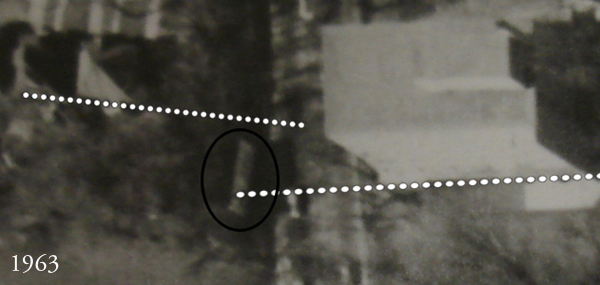

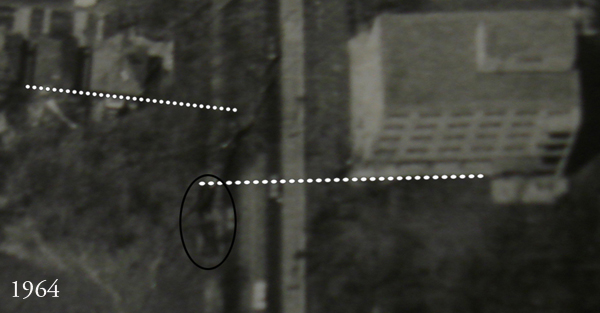

a) I spent some time at the Toronto Archives with my buddy Rami Tabello. We looked at aerial photographs of the area, going back in time, year by year. We discovered that while there have indeed been billboards there for a very long time, the current structures were only built in 1963. Before that, there was a single billboard in that location, rather than two.

b) When I showed the photographs to City staff, they said that the discrepancy in the photos was quite clear to them, but might not be strong enough to be used as legal evidence. The photos are taken at different angles and there are some shadows. They suggested that I would need to find further evidence that clearly showed a single billboard in that location. So I asked around for advice, and Chris Bateman found this amazing picture from 1953:

3) Where is the Billboard registry?

Here’s the real question: Why does a citizen have to do all this work, to ensure that a private company is in compliance with a municipal bylaw? Let’s compare this to other scenarios. The city has the DineSafe program, where each and every restaurant is inspected to see if they are clean and compliant with existing bylaws. Each premise is then given a colour code: green, yellow and red. The colour code is clearly posted in a visible location at the restaurant entrance, and also on the Open Data website.

Here’s the real question: Why does a citizen have to do all this work, to ensure that a private company is in compliance with a municipal bylaw? Let’s compare this to other scenarios. The city has the DineSafe program, where each and every restaurant is inspected to see if they are clean and compliant with existing bylaws. Each premise is then given a colour code: green, yellow and red. The colour code is clearly posted in a visible location at the restaurant entrance, and also on the Open Data website.

Or how about license plates? Every car has to be licensed and the plate is clearly attached to the car. Hot dog vendors, home renovators and TTC buskers all have to visibly show their permits, so members of the public are informed and aware.

I have been told that the city has completed a comprehensive audit of all existing billboards. They know which ones have permits and which ones seem to not have permits. So why isn’t this information available?

City staff could do two things. First, they could make all of this information available online. Any citizen could check the map and see if a billboard had permits or not. Second, they could require that all billboards display a visible permit tag. If the city isn’t sure about compliance, they could use the same colour codes as DineSafe: Green, Yellow, Red.

It’s important for me to point out here that city staff have almost no budget whatsoever for pro-active enforcement of the sign bylaw. They used to, but it was cut from their budget under this current City Council. So what does that mean? It means that city staff will only investigate an illegal billboard if someone from the public complains about it. But, at the same time, they are withholding all the relevant information that a citizen would need, to know if the billboard was legal or not!

I have sent a formal request to the city, asking them to disclose any data they have about billboard bylaw compliance. They haven’t responded yet.

As for the two billboards poking out of the woods on Bathurst Street, City staff have been very helpful so far. They’ve sent an investigator to the Toronto Archives to confirm the authenticity of the aerial photos that I’ve provided. And they are talking to other city staff, including their legal department, about the possibility of sending another “Notice of Violation” to the billboard company (eight years after the first Notice was sent).

Hopefully these signs will come down soon. I have little doubt that they are indeed illegal, and have never had any permits.

But it shouldn’t take this much effort, from a volunteer citizen, to ensure that the city’s own bylaws are being upheld. These larger issues have to be addressed:

• Why is there no public registry of billboards, including information about bylaw compliance?

• Why is the Sign Unit being under-funded, removing their ability to do pro-active enforcement?

• Why is there a veil of secrecy around billboard enforcement? Citizens have a right to know how their public space is being used or abused, and why.

Next: Part III

8 comments

Congratulations on all your hard work in getting to the truth in this matter. I wish more urbanites would go this length to ensure that corporations toe the line when it comes to respecting the city by-laws and preserve what natural areas we are still allowed to enjoy unblemished

Billboard location and permit status should absolutely be released as an open data set. Public access will open up new possibilities to improve enforcement, compliance and data management. Kudos on highlighting a public interest and public space issue desperately in need of a little more open government. Have you submitted this request to the City of Toronto’s open data team as well?

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=9e56e03bb8d1e310VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

Thanks Dave for this interesting article. I look forward to Instalment 3.

Here are few things to consider.

The burden of proof for legal non-conforming status should be on the owner of the sign, not the City. This is the standard applied to non-confoming properties and buildings in the Zoning By-law – prove it remove it or get a variance approved. The City of Toronto has established a Sign Variance Committee that could address such applications.

Secondly, it is possible to remove legal non-confoming signs. The City of Vancouver sought and received an amendment to the Vancouver Charter from the BC government in the early 2000’s to do just that – with a 5 year grace period. Many billboards were removed by the owners as a result and the City had to do very little enforcement to make it happen. A note of caution however – When the City tried to enforce removal of a roof top sign on the Lee Building it had to go to court twice and finally to the Supreme Court of Canada before the sign came down. However that case did establish a good precedent for the enforced removal of non-conforming signs.

In Metro Vancouver municipalities, only the City of Vancouver permits billboard at all. The only exceptions are a few big electronic billboards in some of these other municipalities that got individual Council approval and which generate revenue for the municipality.

Thanks for fighting these difficult battles. I’ve had a similar frustration trying to remove ‘no trespassing’ signs or gates blocking POPS privately owned publicly accessible parks & walkways. Staff were instructed by council to provide the addresses of over 400 identified POPS, but staff argued that it would release only a ‘refined list’ that merited signage, about 100.

http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/pg/bgrd/backgroundfile-59381.pdf

I spent over a year of phone tag attempting to get overworked staff to verify numerous suspected POPS locations. Finally a NY planner went to archives to investigate a single address (Humberstone walkway between Everson and Oakburn). It was confirmed to be POPS, and a letter was sent to the townhouse community management. The planner informed me that the compliance request was ignored, then, like others, the planner stopped responding.

‘No trespassing’ signs remain and it is one of the vast majority of POPS locations that city staff deemed unworthy to reveal in its public list.

My take: city staff are under-resourced, while developers & property managers (like signage reps) are organized and influential.

Maybe what is needed is a chain saw or cutting torch!

Now is the time to put the question to every candidate for mayor and Councillor in the up coming election. Put them on the spot and hold them to it after election.

Permit on the sign is the right idea, Dave, similar to what’s required on things like clothing donation collection boxes.

Problem is signs are a mess in general. All of the A-frame signs that businesses put out… all of the sandwich boards for new condo developments… those are all required to have permits and the permit number is supposed to be shown on the sign. Never happens, and enforcement is pretty much non-existent.

Do you have any video of that? I’d like to find out more details.