The Toronto York Spadina Subway Extension (TYSSE) is advancing towards completion in the Northwest end of the city. The project is now scheduled to open December 2017. When complete, it will be the first extension to the subway network in nearly two decades, a period in which the population of the City is projected to grow by 1/2 million people. Subway construction in Toronto started with the Yonge line in 1949. A lot has changed in the intervening 66 years: construction has become substantially more sophisticated, quieter, cleaner, less obstructive and undertaken on closed sites for health and safety. Paradoxically, the improvements in subway construction mean that potential transit users have less understanding of what is actually happening, even as people maintain their excitement for big construction.

The first section of the Yonge subway was built in an open trench, the remnants of which are visible to riders between Rosedale and Yonge-Bloor Stations. Mostly out of sight, the construction of TYSSE has been ongoing since 2010; it resembles the 1949 construction only in its final goal: to build a subway.

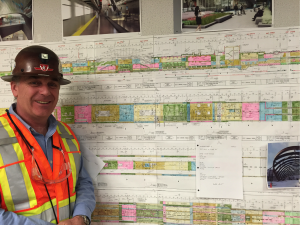

Last month, I went on a tour of the York University and Vaughan Metropolitan Stations. (Disclosure: I worked on the design of these stations from 2009 to 2012). These two stations are arguably the most important of the extension. Transport to York University will be revolutionized by the subway, which will replace hundreds of buses. The Vaughan Metropolitan Station is the first TTC Subway Station outside of Toronto and Vaughan is planning transit-oriented development based around the station.

Subway construction has moved away from the old trench method for safety and convenience. We would no longer tolerate an entire road ripped up for years while a subway is laid down. Opening a trench is a bigger risk to buildings than concrete and steel supported modern excavations. Unsupported trenches are hazardous for the people who work in them.

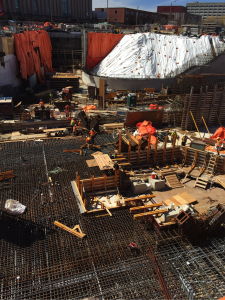

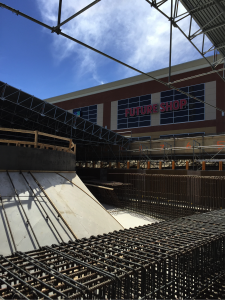

The TYSSE stations are being built using the “cut and cover” method. First, support for a deep excavation was built from the surface using piling machines, then a big hole was excavated which is now being filled in with the station. The construction of York University Station was about halfway back to ground surface when I visited; Vaughan Metropolitan Centre is noticeably further ahead – the underground station structure is complete and the surface has been re-established.

By nature of being works in progress, both stations were a mix of temporary and permanent structure. Steel props over a meter wide hold the excavation open at York University while steel reinforcement cages are placed and concrete is poured. The construction of the station is a delicate dance between speed, accuracy and the realities of construction materials. Concrete, the main material of both stations, gets hot as it sets. If too much is poured in one go the heat will cause cracking and permanent damage to the station. A rough rule of thumb for subways is that 600 cubic metres can be poured at once. While concrete looks hard shortly after pouring, it takes a long time to become strong. After 7 days concrete will have achieved about 75% of its strength and will be nearly full strength by 28 days. This set time controls the rhythm of construction. The upper parts of the stations can’t be poured until the concrete underneath is strong enough to support it. Along TYSSE much of concrete will be exposed in the final structure; which raises an extra challenge: aesthetic pouring requires particular care to avoid openings that will require structurally valid but unappealing repair patches.

Vaughan Metropolitan Station, at 530 metres, is the longest of the extension; it will include a crossover so trains can turn around and tail tracks for storage. When I visited they were getting ready at to carry out the biggest concrete pour in the history of Toronto. Two thousand cubic metres of concrete were to be poured over 24 hours to form the main entrance of the station. Hundreds of temporary supports were installed throughout the platform level to hold the weight of this massive pour. A pour this size is well outside the standard and requires special preparation and construction techniques. Among other complications, mixed concrete will ‘go bad’ in the truck and must be poured within a few hours of being prepared. Achieving this on a big project requires detailed coordination between the construction site, the mix plant and the drivers to make sure the concrete gets to site and is placed in its usable window.

Geotechnical engineers joke that our sites look the same before we start and after we finish. After five years of heavy construction, the TYSSE structures are almost done and buried. In the end, very little will show at the surface of the massive structures currently being built.

Shoshanna Saxe is an engineer from Toronto. Say hello on twitter @shoshannasaxe

One comment

A correction with:

“When I visited they were getting ready at to carry out the biggest concrete pour in the history of Toronto. Two thousand cubic metres of concrete were to be poured over 24 hours to form the main entrance of the station.”

One, technically it’s Vaughan and the project probably holds the title for the biggest concrete pour in that city.

Two, the CN Tower would probably hold the Toronto title as it contains over forty thousand cubic metres that took several months of continuous 24-hour pouring to complete.