A few years ago, Stats Canada conducted a survey exploring disabilities and found that 3.8 million adult Canadians identified as “disabled.” However, a number of demographic groups, including individuals living with temporary disabilities, individuals living in institutions, and individuals under fifteen years of age were not accounted for. Most notably, a large number of individuals living with invisible disabilities were excluded from this and similar types of surveys.

Invisible disabilities covers a huge swath of experiences and conditions such as chronic pain, vision impairment, learning differences, brain injuries, and mental health conditions. Given the complexity of these experiences and conditions, and our emerging understanding of them, it’s safe to surmise that a lot more than 3.8 million Canadians are living, and by extension commuting, with both visible and invisible disabilities.

Georgina’s mother tells me that people immediately notice that her daughter is tall for her thirteen years, beautiful, and very funny. What’s less obvious is that Georgina lives with Autism Spectrum Disorder and experiences Myoclonic Seizures due to epilepsy. In spite of her challenges, Georgina, like many others living with disabilities, enjoys a full life. Her schedule is filled with urban excursions, swimming, and personal appointments. In some ways the main challenge faced by Georgina and her family isn’t the fact that she lives with invisible disabilities; it’s the difficulty getting her around.

Georgina requires one-to-one care and will never be able to travel on transit alone. As a result, Georgina’s mother left a promising career to work within the home providing care for Georgina and her two other sisters. The family lives on Georgina’s father’s income so accessible transportation is imperative for mitigating sky-high child care costs, accessing quality health care, and ensuring that all three children are provided with enriched experiences.

In spite of this, the family’s request for an accessible public transit service for people living with disabilities was denied.

Twice.

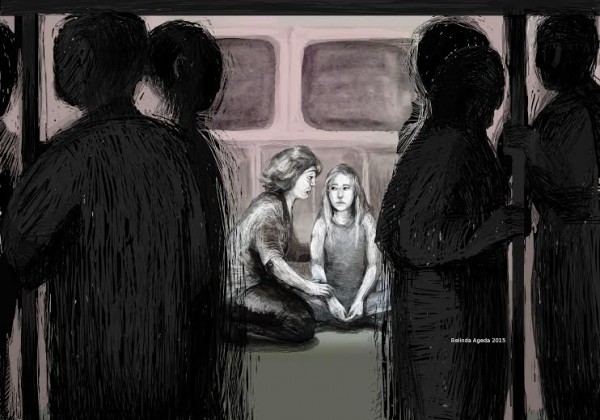

The rationale for these denials was that Georgina is able to navigate stairs. What was not properly considered is the fact that when Georgina experiences seizures she must be immediately moved into a sitting position on the platform or transit vehicle floor, and then wait out thirty to one hundred little jerks and ticks. By the time the seizure passes, Georgina and her mother (or support worker) have travelled four or so stops beyond their destination. On other days frantic rush hour crowds and the train’s roaring approach cause Georgina considerable distress due to autism. Sometimes these experiences are so upsetting that Georgina becomes inconsolable and plans are thwarted.

Other children commuting with invisible disabilities face similar challenges. A Toronto Star article features Farida Peters, a mother who has resorted to wearing a sign on her back which reads, “My son is 5 years old and has autism. Please be patient with us. Thank you.” Each day she and her son Deckard take one bus and two trains to his behavioural therapy. The sign is intended to offset negative passenger responses. Deckard has been scolded, shoved, and criticized for not making eye contact by complete strangers.

In addition to children, a growing number of adults with invisible disabilities encounter challenges while on transit.

Jason Bosher a Vancouver resident who lives with rheumatoid arthritis and spinal injuries, unpacks his experience of travelling on public transit in pain. He speaks about the difficulties of disclosing his condition, running the risk of asking a fellow commuter with an invisible disability to give up their seat, and being targeted by belligerent passengers who doubt him based on his appearance. Another commuter who describes herself as a “brightly coloured Goth” echoes Jason’s concerns in a simply shot video through a series of surprising and heart breaking incidents.

Thanks to people living with invisible disabilities speaking out, campaigns like this one led by the Rick Hansen Foundation, and progressive transit systems like Metro who launched this ad campaign, public awareness is growing. However, the Ontario Human Rights Commission highlights unresolved transit issues faced by seniors with mobility challenges and individuals living with visible disabilities. This means timely systemic progress on invisible disabilities is unlikely.