By Zack Taylor

Few topics have pre-occupied Toronto’s budget watchers more over the past decade than the city’s land transfer tax (LTT). People love it or hate it.

For its advocates, the LTT was the revenue stabilizer the city needed at a time when each budget cycle began with a yawning gap between expenditure demands and money available to pay for them. This tax was also a shining example of the city’s mature exercise of its new powers under the 2006 City of Toronto Act.

For others, however, it represents a dangerous addiction to a revenue source that will certainly dry up when the housing market stalls, as well as a ‘bad tax’ that increases housing prices and makes Toronto uncompetitive relative to its neighbours.

First, a few words on what the LTT is and how it works. For decades, the provincial government has charged a duty, calculated as a small percentage of the purchase price, every time a property is sold. Many jurisdictions do this. First-time homebuyers are exempt. The percentage increases with the value of the property. Governments like land transfer taxes because they are invisible levies: it disappears into the closing costs along with various fees, and therefore into the housing price. For most homebuyers, the land transfer tax vanishes into their mortgage, which spreads out its payment. When the housing market is humming, it generates a lot of revenue.

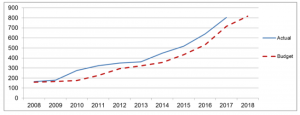

The City of Toronto Act, passed in 2006, was intended to end the annual trip to Queen’s Park for one-time bailouts by making the city more financially independent. One of the “revenue tools” the city adopted was its own LTT, piggybacked on top of the provincial one. Fuelled by the city’s property boom – total assessed property value almost doubled between 2009 and 2018 – the LTT has been enormously lucrative, pumping hundreds of millions into city coffers. Today, it accounts for about 6.3% of the city’s $13 billion operating budget (the city forecasts $818 million in LTT revenue in 2018).

Due to its revenue-generating power, the LTT has proven impossible to abolish, as Rob Ford discovered.

Figure 1: LTT revenues have exceeded forecasts since its introduction in 2008

Source: City Budget Summary 2018, p. 51.

What is often overlooked in debates about the LTT is that it has been the city’s most direct and substantial way of extracting public benefit from Toronto’s housing boom – way larger than development charges and the incremental rise in property tax revenues due to assessment growth. There has been endless debate about “land-value capture,” area-specific property surtaxes, development charge reform, and so on, to fund much needed infrastructure repair and expansion. But the LTT has done this work most effectively.

Yet all of that LTT revenue goes to the annual operating budget – mostly salaries – not the capital budget. While Toronto residents receive high property tax bills because their properties are more valuable than those in other cities, their property tax rates are low compared to other cities. In other words, the LTT shields Toronto homeowners from property tax increases; it subsidizes low residential property tax rates.

I have a modest proposal: Over the next decade, Toronto council should shift LTT revenues over to the capital budget. We must recognize that, as a device for capturing public benefit from rising property values, the LTT is a windfall gain we shouldn’t count on. But when it comes in, we should direct it appropriately. Public benefits captured from the city’s housing boom should pay for the hard costs that the boom generates.

For me, the most direct analogy is to natural resource revenues. Smart jurisdictions, like Norway, recognize that the party won’t last forever, and so they direct their offshore oil royalties to an investment fund for future use. Less judicious jurisdictions, like Alberta, use their windfall gains to subsidize low taxes. Alberta is now learning what happens when public expectations of big spending and low taxes collide with collapsing windfall revenues. (In 2005, energy royalties accounted for 40.4% of provincial government revenues in Alberta; today the figure is 5.7%.)

Are Toronto residents and politicians prepared for the double-digit property tax increases that will be required to compensate for LTT revenue collapse if the housing boom ends – as it did in the early 1990s? Better to address this problem gradually, and before it happens.

What would this fix look like? Let’s imagine that council directs an increasing share of LTT revenues to the capital budget every year – 10% per year over ten years, at which point it would go entirely to the capital budget. Gradual property tax increases would make up most of the difference. Let’s assume that the housing market cools and the LTT brings in an average of $600 million annually over the next ten years. To raise an additional $60 million a year would require an annual residential property tax surtax of about 2%, which translates into an additional $60 for the average household.

At the end of ten years, an additional $3.3 billion would have been diverted to capital projects, an amount that could seed much larger investments by leveraging new borrowing, federal grants, and public-private partnerships. While these additional dollars won’t wipe out Toronto’s $40 billion ten-year capital plan on their own, it will certainly help. (Let’s remember that three-quarters of the plan is currently unfunded). There’s a political windfall, too: people will accept higher taxes if they know where the money is going and the results are visible.

The bottom line: As Toronto’s city managers have advised council since the LTT came into effect a decade ago, it’s a bad idea to depend on unpredictable windfalls to fund everyday expenditures. Let’s recognize the LTT for what it is: a way to capture public benefit from the housing boom, while it lasts. Redirecting the LTT from the operating to the capital budget will convert all that revenue into concrete benefits that future Torontonians will enjoy for decades to come.

Zack Taylor is director of the Centre for Urban Policy and Local Governance and assistant professor of political science at Western University. Follow him on twitter at @bigcitypolitics.

One comment

Another thought: land transfer taxes – provincial and municipal – are paid by the purchaser, not the vendor. It would make sense for the vendor to pay, as that’s where the cash is. Purchasers scramble to come up with the money to buy, when vendors are flush with the cash proceeds of their sale. It’s a lot of money – about 3%, now, in Toronto.