Amazon’s notoriety for exploitative work conditions, harmful environmental practices, corporate tax exemptions, and stripping jobs away from small community businesses have intensified calls to boycott Amazon and support local retailers. Yet Amazon has had little difficulty in recruiting employees for the launch of its Scarborough – YYZ9 location. Conversations I’ve held with some of these workers have allowed them to illustrate their stories in Scarborough, which address significant themes of community engagement, equitable access to income through securing non-precarious employment, and ensuring safe pedestrian travel

In 2019, Amazon announced plans to establish a new fulfillment center in the Greater Toronto Area near Steeles and Tapscott Road within northeast Scarborough, marking the first fulfilment center in the City of Toronto. Real estate developers Broccolini began construction of the one-million-square-foot fulfillment center on land intended for industrial uses, and it opened in August 2020, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

It was Canada’s twelfth fulfillment center and the seventh in Ontario, with other operations facilities located in Brampton, Mississauga, Milton, Caledon, and Ottawa. Amazon’s press release stated that its establishment would create more than 600 jobs, and that it would offer full-time employees competitive hourly wages and medical, vision, and dental coverage, in addition to other job-specific perks.

Some might be wary of the crowded working conditions associated with a warehouse position, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is evident from a simple Google search, and from speaking to employees of YYZ9, both current and past, that Amazon application inquiries are growing rapidly. Much of the response Amazon has garnered in Scarborough results from what Arun Chandramohanan, a worker who immigrated to Canada from India recently (as of September 2020), describes as “being in need of a job to pay my bills, especially during the lockdown.” Arun’s statement is reflective of the duality of Amazon in Scarborough, as both problematic and useful. .

Much of the popularity of warehouse jobs in Scarborough can be linked to sentiments of proximity and familiarity. A common theme amongst the workers who shared their experiences was that having the location of the warehouse be within Scarborough, which is relatively close to most of their homes, is what drew them to the job in the first place. Waris Ahmadzai, a refugee from Afghanistan, tells me, “the work location is very convenient to me because it is in Scarborough and not too far from my home.” Similarly, Brad Arsenault, born and raised in Scarborough, shares that “I chose this job for two reasons, pay and ease of commute daily. This location is very convenient, it’s about a 15-minute drive from my house.” In other words, the convenience of getting to work is what’s motivated many Scarborough residents to seek the Amazon warehouse as a means of employment.

Reflected within the diversity of employees, a worker who wished to remain anonymous explained that the warehouse has fostered an opportunity for immigrant mothers with language barriers to seize employment, as their representation in the workplace has led to communication between workers that otherwise wouldn’t have been possible in predominantly English-speaking work environments. Her first language is Tamil, and many of her coworkers can speak Tamil as well. Our correspondence was limited due to the lack of a translator and limited English, but it was clear that the comfort she feels within her workplace is rooted in the fact that the same language is being spoken by her co-workers.

Relatedly, Amazon has allowed for connections and a sense of community to form between workers. Arun, who had no friends or family upon immigrating to Canada, earnestly expresses, “I like the fact that there are people of all ages, backgrounds and cultures at the YYZ9 facility. In fact, it’s the people working with me that makes me go to the monotonous work every day. Made some good friends too, in this short while.” Brad is also of the same opinion, as he also believes that “your coworkers are by far the best component of the Amazon workplace,” as is Waris, who agrees that “the thing I like about the job is that is the people are fine – I can also understand the different languages that are spoken in our warehouse.”

The reality is that jobs are hard to find in Scarborough, and often BIPOC, immigrant and refugee workers are excluded from conventional white collar jobs because of a lack of qualifications or experience and, instead, must look to work in areas like warehousing for employment. For example, in India Arun acquired an MBA and a civil engineering degree. The types of work he frequently did were “in management consulting, advisory and project management. I was an advisor for various state governments in India in areas like public procurement, policy analysis, and project structuring.” In Canada, Arun has not been able to secure employment within his area of expertise, and with a lack of references to confirm his work experiences, at Amazon, when he applied for the job, “I submitted that I only had a high school diploma, and that landed me this entry level position at the Amazon Fulfillment Center.”

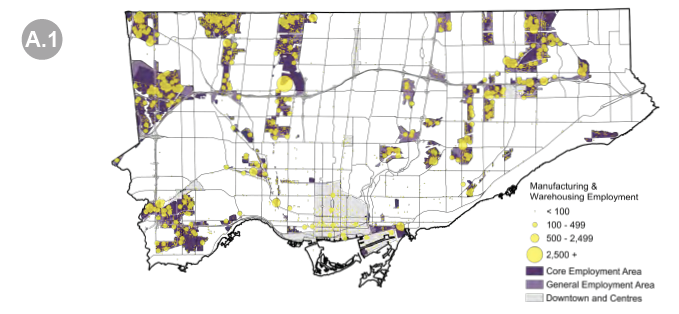

According to the 2019 Toronto Employment Survey, Scarborough, referred to as the East, is among the five Employment Monitoring Areas (EMAs) formed to analyze Employment Area activity across the City. In Scarborough, the Transportation and Warehousing sector accounted for 9.9% of employment and, as a sector, grew the most in the East EMA since 2014, adding 2,680 new jobs (an increase of 37.6%) (p. 27). Undeniably, warehouses like Amazon are a fundamental component of job creation and localized economic growth within Scarborough.

By delineating the duality of Amazon, we can critique the implications of Amazon’s larger socio-economic behaviours and still recognize the essential workers in Scarborough who are heavily reliant upon the warehouse. To reconceptualize what it means to work at the Amazon warehouse, city planning processes must prioritize the safety of workers by considering transit and mobility as fundamental to the conception of employment areas. Currently, transit accessibility within the area is severely lacking, with an absence of proper sidewalks, leaving pedestrians with a difficult and dangerous decision to choose between walking in the mud or on the busy roadway itself (as revealed in a Walk Toronto post led by Sean Marshall. Disclosure: I have recently joined the steering committee of Walk Toronto).

When asking workers what their means of transportation was, public transit was the popular answer. The public transit routes most often taken by workers are either the 102B\C Markham Road or the 53B/953B Steeles East bus. The 102 Markham Road bus, as reported by Sean Marshall in April 2020, has been struggling with morning rush hour crowding, which has resulted in reducing loading standards to maintain proper social distancing. Despite the TTC’s announcements of increased service on the busiest routes such as the 102, workers are still encountering crowding during both rush hour and off-peak travel times. Due to the delays, Waris voices his frustrations that “it is harder to get to work on time nowadays.” Meanwhile, in January 2021, the TTC announced it was diverting the route of the 53B Steeles East bus, to directly serve the Amazon fulfilment center and reduce workers’ travel times.

Despite the improvements being made for service workers, Arun points out that the distance from the bus stops to the actual facility results in “a 15 min walk from Passmore Avenue to YYZ9 before and after shift on the dark and slippery path with no sidewalks, which could have been avoided.”

With winter conditions, workers voice their concerns with ice, slipping, and unclear pathways, especially after heavy snowfall. The planning oversight does not take into account AODA standards in terms of the paces at which people with diverse abilities move, and the safety issues posed to people with mobility issues who do not have defined spaces for them to use. It is also important to note that while Brad drove to and from work without facing any endangerment within his commute, the anonymous worker I spoke to favored being dropped off by her husband daily, as it felt safer to her than utilizing transit. Her comments reflect the prioritization of driving in suburbs like Scarborough, as the geography of the facility is intended for car use due to wide roads and ample parking spaces – even then, there is only one entrance and exit to the street.

To ensure that the same mistakes aren’t made for future employment sites, city planning officials must strive towards putting in place appropriate pedestrian infrastructure and transit services during the planning stages, and before the approvals and construction processes. As the pandemic continues to linger, the demand for jobs closer to home will continue to make waves amongst Scarborough residents, especially with the discontinuation of the SRT – Scarborough Line 3 in 2023. It is now up to decision-makers to finally hear and act upon these concerns.

Special thank you to Arun Chandramohanan, Waris Ahmadzai, Brad Arsenault, and the anonymous worker who took the time to speak with me.

Top image courtesy of Sonali Praharaj.

Aria Popal is a planner from Scarborough who completed her research at York University’s Faculty of Environmental Studies (MES) on the topic of Missing Middle housing in Toronto’s Yellowbelt, as an approach, a strategy, and a discourse to moderate the housing affordability crisis. She is passionate about land-use planning processes that encompass notions of inclusivity, accessibility, and affordability. Follow her on Twitter at @ariapopalTO

2 comments

“The reality is that jobs are hard to find in Scarborough, and often BIPOC, immigrant and refugee workers are excluded from conventional white collar jobs because of a lack of qualifications or experience and, instead, must look to work in areas like warehousing for employment. For example, in India Arun acquired an MBA and a civil engineering degree. The types of work he frequently did were “in management consulting, advisory and project management. I was an advisor for various state governments in India in areas like public procurement, policy analysis, and project structuring.”

Couple things.

A lack of qualifications is mentioned as a barrier to a white collar job. That is fair isn’t it? I am not hiring someone without the qualifications.

Second, an immigrant can find white collar jobs if they have the qualifications/experience and they have been. I know many. On a previous team I was on (white collar, high pay), I’d say 80% of the team had been in the country for less than a year. One of our team created a whatsapp group specifically to help people out in our field and jobs are still getting posted there all the time. Networking is very important for an immigrant and with the internet they have the tools previous generations did not have.

This was a really well put together article and very insightful.