Cycling along Barrie’s waterfront trail, on a cloudless day with the sun burnishing the sky, the trees quiet in the still air, I came across a heritage plaque that stopped me in my tracts.

It was in honour of Hewitt Bernard, who was born in Jamaica in 1825. The plaque said he immigrated to Canada and settled in Barrie in 1856. I pondered, who was this Jamaican, and given his birth year, was he born free or enslaved? And then it occurred to me to wonder if he was Black or white?

I took a picture of the Ontario Heritage Trust’s plaque and then got back on my bike. Today’s daytrip was a cycle to the two Black history sites I knew of in Barrie. But first, I took a quick detour to the farmer’s market for fruits and fresh falafel, then followed the Oro-Medonte Railtrail, a recreational trail built atop a disused railway line, around Kempenfelt Bay. I stopped at the parking lot at 1 Line South, for here was an Ontario Heritage plaque to the Black Settlement in Oro Township.

“The only government-sponsored Black settlement in Upper Canada, the Oro community was established in 1819 to help secure the defence of the province’s northern frontier,” the plaque read. “Black veterans of the War of 1812 who could be enlisted to meet hostile forces advancing from Georgian Bay were offered land grants here. By 1831 nine had taken up residence along this road, called Wilberforce Street after the renowned British abolitionist. Bolstered by other Black settlers who had been attracted to the area, the community soon numbered about 100. The settlement eventually declined, however, as farmers discourage by the poor soil and harsh climate gradually drifted away. Today only the African Episcopal Church erected near Edgar in 1849 remains as a testament to this early Black community.”

The mosquitos were having a picnic on my bare skin. I rummaged through my saddle bags and came up empty handed – no bug juice. A couple paused and said the bugs were worst where the trail went through the woods. They were so bad that the couple had given up the idea of cycling to Orillia; they had no mosquito repellant either.

Orillia was not on my plans, not for today. I turned inland and cycled slow along winding country roads for the next two hours or so. These roads were quiet. I did not meet another cyclist. A car or two whizzed by every ten minutes. This was farm country, where the steel grain elevators were the tallest objects in the landscape, shimmering in the sun as if they were beacons of hope.

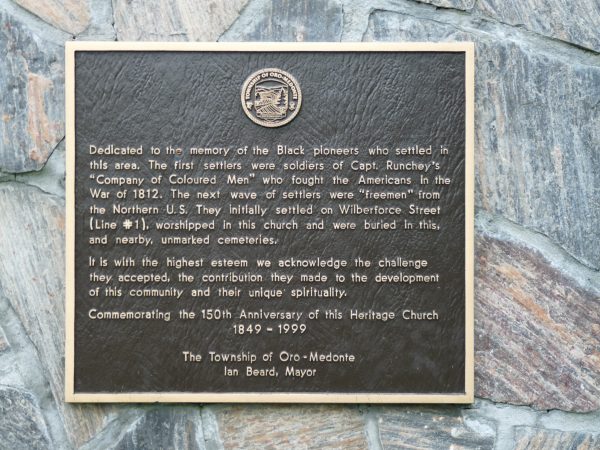

The Oro African Methodist Episcopal Church hugged a crossroads in the hamlet of Edgar. The simple log cabin church is local museum and a National Historic Site of Canada. The grounds were neatly trimmed, and baskets of geraniums sat next to the front door. I walked around the church, reading the many heritage plaques on the site. I remembered talking to a Black man at the farmers market, who said he was a direct descendant of the Black refugees who worshiped at this church. He had told me to look out for his family name among the gravestones and plaques, and I found it.

Sitting on one of the picnic benches, I ate my lunch and googled Hewitt Bernard on my phone. He had lodged like an itch my mind and I had to know who he was, and if he had any connections to Black history. I found out that Bernard was a minor but important figure in Canadian history. But I was more interested in his family tree rather than his political legacy.

Bernard worked for Sir John A. MacDonald, the first prime minister of Canada. The two were also brothers-in-law, as MacDonald married Bernard’s sister, Susan Agnes Bernard, who became Lady Agnes Macdonald. The Bernard clan had deep roots in Jamaica, where both siblings had been born.

The Legacies of British Slave-ownership is an online database by University College London, that tracks the payments made to slave owners by the British government to end the centuries of trade in Black bodies. The database reveals that the siblings’ father, Thomas James Bernard, was awarded about £1,492 for the loss of 80 enslaved people on four plantations in Jamaica. This was a fortune, when the average income of a labouring family in Britain was about £41. In Canada, the Bernard’s inheritance from slavery ensured they were members of the elite.

The slavery compensation payments were so large that they consumed 40 per cent of Britain’s national budget. The government borrowed the money and did not finishing repaying the loan until some 200 years later, in 2015. The Treasury’s later tweet about the final repayment did not go down well, as its celebratory tone was tone deaf to the centuries of brutality that had made Britain rich.

The search for Black history is often what inspires my adventures and visits to hamlets, small towns, and other places and events in Canada. The Black history is there, though one has to dig hard to find it. It does not help that official tourism publications, like Parks Canada’s Guide to the National Historic Sites of Canada, does not contain a single Black history site. And its Guide to the National Parks of Canada does not have a single photograph of a Black person. These publications are merely continuing the long Canadian tradition of erasing Black people and slavery from its history.

With my belly full and the mental itch scratched, I got back on my bicycle. This time, I took the main road as it had a wide shoulder, even though it was busier than I would have liked for cycling. It was a fast ride, downhill, all the way back to Barrie’s waterfront. Along the way, I spotted heritage plaques to Nine Mile Portage, an Indigenous trail and a key route in the War of 1812. How many Black soldiers hiked along that trail, I wondered? That question is all I need to plan another adventure ride in the area. At Barrie GO Station, I put the bike back on the train and in an about an hour I was home in Toronto.

Jacqueline L. Scott is a PhD candidate at the University of Toronto. Her research is on the crossroads of race, outdoor recreation, and the broader environmentalism. Follow her on Twitter at @BlackOutdoors1