As Torontonians head to the polls for the ninth municipal election since amalgamation, how many voters will actually cast a ballot? With mail-in ballots available to all eligible voters for the first time, and eight whole days of advance polls ahead of the election day on October 24, voting should be easier than ever before. But all signs point to another lethargic turnout, with an incumbent mayor likely to win re-election, and no particular issue so far that has captured Torontonians’ imagination — or their wrath.

In 2014, 54.7 percent of all eligible voters went to the polls, the highest turnout in over 30 years. That year, there was a competitive three-way mayoral race, even when incumbent Rob Ford dropped out for health reasons, with Rob’s mercurial brother, Doug, taking his place (and coming in second place). But in 2018, only 40.9% of electors bothered to vote. Mayor John Tory cruised to victory despite a late challenge by former chief planner Jennifer Keesmaat, while a sudden reduction in the number of wards imposed by Doug Ford’s newly-elected provincial government confused voters and crushed the hopes of many council hopefuls and their supporters.

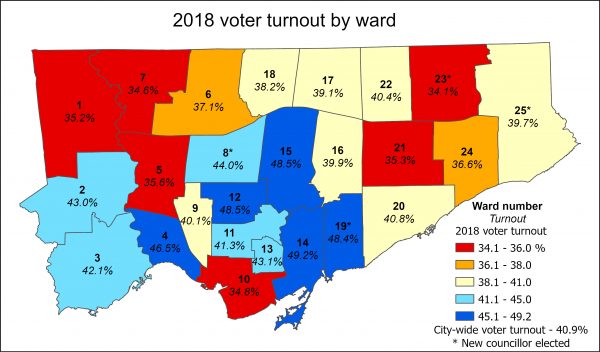

Even though 769,000 electors cast a ballot that year, voter turnout varied across the city, with Toronto’s most affluent wards seeing the highest numbers of voters cast a ballot, while wards in the inner suburbs, particularly in the northwest and in Scarborough, had the lowest turnouts. Four new councillors were elected (Brad Bradford, Mike Colle, Jennifer McKelvie, and Cynthia Lai, though for Colle, aged 73 in 2018, it was a return to municipal politics after 23 years as an MPP), but only Colle and McKelvie defeated sitting incumbents.

Ward 14 Toronto-Danforth had the highest turnout, where 49.2 percent of electors cast a vote. It was followed by Ward 15 and Ward 12 (both of which had 48.5 percent turnout) and Ward 19, where 48.4 percent of electors went to the polls. In contrast, in Ward 23, Scarborough North, only 34.1 percent of eligible voters showed up at the polls. In Ward 7, Humber River-Black Creek, just 34.6 percent of electors voted. Ward 10, Spadina-Fort York, had the third worst turnout, with just 34.8 percent.

Though competitive races at the local level can attract voters to the polls, there is little evidence of this being a factor overall. With the sudden reduction from 44 wards to 25 (in an election where there was to be a new map with 47 council seats up for grabs), there were several wards that had incumbents running against each other, and others where a high-profile challenger put their name forward. However, the only deciding factor appears to be the relative affluence of each ward.

Ward 19 had a very tight race between Matthew Kellway, former NDP MP for Beaches-East York, and former city planner Brad Bradford, who had the endorsement of outgoing councillor Mary-Margaret McMahon and Tory. Just 288 votes (0.9% of the vote) separated Kellway from Bradford, who eked out a win. However, even with an open race in Ward 23 (where Cynthia Lai won with just 27% of all votes cast), it had the lowest turnout in 2018. In Ward 1, where incumbents Vincent Crisanti and Michael Ford went against each other, voter turnout was the third lowest (Crisanti is running again in Ward 1 this year). The low turnout in Ward 10 Spadina-Fort York may be explained by the high proportion of younger residents and renters, who historically vote in lower numbers than older homeowners.

Despite urbanist and safe-streets advocate Gil Peñalosa’s entry in the mayoral race, John Tory is expected to win an unprecedented third term in office. Though there are seven seats without an incumbent running this year (Wards 1, 9, 10, 11, 13, 16, and 18), and there are more ways to vote than ever before, it is unlikely that voter turnout will increase substantially in 2022. With so much riding on the makeup of City Hall — housing policy, transit, policing, the state of Toronto’s public spaces, and action on climate change — the need for effective leadership has never been greater. This is why voter turnout — and civic engagement — matters.

See the full-sized map here:

One comment

To improve voter turnout we should stop forcing voters into a corner.

We should simply drop the rule on “spoiled ballots” and let people freely vote for as many options on their ballot as they want, with the winner still being the one that gets the most votes.

This is known as “Approval Voting” because the votes — the marks on the ballot, not the entire ballot itself — indicates that the voter approves of those candidates.

Approval Voting would allow people to vote for their preferred choice AND for any other choices that they consider acceptable. Approval Voting is like Ranked Ballots but without the “dance” of dealing with rankings.

Approval Voting is simple to explain, and — since it could use the same ballots we have today — it’s just as simple for counting votes.

Approval Voting could change peoples’ attitude about elections.

When people have been freed from being forced to choose just one single “safe” candidate, freed from the unfairness of “vote splitting” and freed from the mental gymnastics of “strategic voting” to try to block candidates that they fear, then they will be more willing to actually go out and vote.