UPDATE NOV. 10, 2023: After years of study, city council voted 18-2 to adopt the new Waterfront East LRT alignment, a three-phase project that will involve rebuilding the streetcar loop between Union Station and Queen’s Quay, extending the new LRT line east along Queen’s Quay, and then constructing the so called Cherry-Villier’s Loop, which will link to the Ontario Line and then run south along Cherry, and east along the rebuilt Commissioner’s Street in the Port Lands. Earlier version included proposals like a people mover between Union Station to Queen’s Quay. The council decision enables City officials to advance the engineering to the 60% level, which is basically shovel-ready. But there’s still no funding for the overall project.

Toronto surely must be one of the very few big cities in the world which somehow manages to unlearn the business of building transit, even as it spends ever more on the same.

This week brought the eye-rolling news that the City won’t be able to operate the two new LRT lines — Finch West and the cosmically stalled Crosstown — due to lack of funds.

Meanwhile, Council’s executive committee received a progress report on the perennially mired Waterfront East LRT, which indicates that the $2 billion-plus project will continue to be funded by bake sales and silent auctions, despite massive, incontrovertible evidence that delaying transit construction into this burgeoning part of the downtown will only make it costlier, less effective and more inconvenient. Not maybe. A 100% certainty. And yet…

Here’s a parable about how to do this kind of thing properly, i.e., by getting the order of operations correct, from another city with an extensive water’s edge brownfield zone. Late last month, I spent a week in Berlin courtesy of the Goethe Institute and the German government, ostensibly on a junket about smart cities. But we took a day trip to Hamburg and got a tour of HafenCity, a waterfront revitalization project that bears some striking similarities to our own, except for some crucial points of differentiation, about which more in a moment.

As with Waterfront Toronto, HafenCity traces its roots to a failed Olympic bid and, before that, a part of Hamburg’s storied port zone that no longer met the needs of its major shipping and industrial operations. Both Waterfront Toronto and HafenCity are about the same vintage (2002 and 2000, respectively), and both involved somewhat radical approaches to urban development on brownfields lands that few people used, much less envisioned as places to live.

In the 1990s, Hamburg’s historic port zone was more or less completely cut off from the city’s core. Only a few thousand people worked there. Besides the canals lined with 18th century warehouses, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the 157-ha area held a power plant and some aging port facilities, but little more.

As architect Uwe Carstensen, a long-time planning consultant to HafenCity, explains, the redevelopment process began with a handful of key moves: the mayor at the time established a private company owned by the City of Hamburg to oversee the development, but didn’t publicize that move in order to prevent real estate speculation. He then initiated the practice, still in use, of holding international competitions to drive virtually every aspect of the area’s planning, architecture and urban design. HafenCity officials then negotiated binding agreements with the developers of individual plots, ensuring they’d build what had been specified in the winning proposals.

But the lynchpin to the whole exercise was a move that is both wonderfully simple and blindingly obvious from a planning and financial perspective: the city extended the subway directly into the middle of this new area, in advance of redevelopment. Imagine.

Hamburg’s regional transit agency broke ground on a new U-Bahn line into HafenCity in 2007. Construction began the following year, and the first station opened in 2012. The line was extended somewhat further and the last station on this spur opened in 2018. The cost of the first segment was a skinny €325 million, with Germany’s federal government fronting 40% of the capital outlay.

Today, scarcely a decade later, HafenCity is almost completely built out — primarily with mid-rise, mixed use buildings, as well as offices, a landmark cultural centre, a university campus, schools and childcare facilities. About 40% of the land is designated as public open space or privately owned public space.

The population stood at almost 5,000 in 2019, but the tallies have risen since then. Carstensen says the number of residents will eventually reach about 17,000, living in some 8,000 homes that includes a mix of social housing, condos and market rental. The area also supports 45,000 jobs because, well, transit.

HafenCity’s planners didn’t banish cars completely — the parking spot ratio is .4 spaces per unit, but the garages, which are partially below grade, serve a dual purpose, in that they provide flood protection in a city where flooding is an increasingly common occurrence. The reality is that when you walk around this new neighbourhood, you don’t see lots of cars.

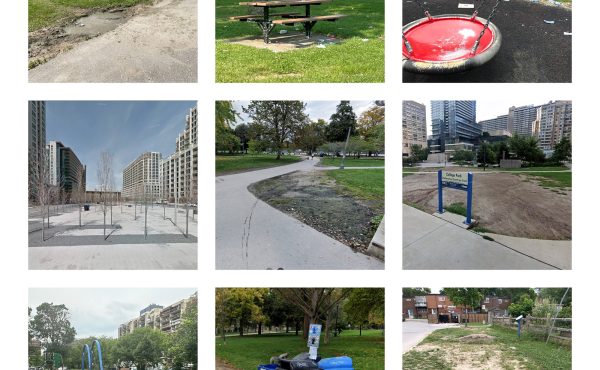

I don’t want to argue here that Waterfront Toronto has been twiddling its thumbs — there’s been a substantial amount of development in the East Bayfront and the West Donlands over this same period. But Queen’s Quay East remains a speedway — wide enough for an LRT that may never arrive.

As for the Port Lands, well, who knows? We’re building a fantastic piece of green infrastructure down there — the new naturalized mouth of the Don, which should, by all rights, become a regional destination. But not by transit.

The report that landed at executive committee recommends that the City spend $135 million to continue the design and engineering work on the Waterfront East LRT, with about half of that sum coming from the city’s various rainy-day funds. Yet the big capital outlay is nowhere to be seen, and it seems increasingly likely that development will precede the provision of rapid transit service — a formula that would likely cause the HafenCity planners to smirk behind their hands.

By building out the Port Lands in Toronto’s usual ass-backwards way, we ensure the developers will be thinking about the cars the eventual owners will need to keep at hand if they buy units out there. The accessibility conundrum means we’ll be baking in both the operational and embedded carbon to the built form of the redeveloped Port Lands, cementing in place travel habits that will be hard to break, ensuring a cranky audience of condo owners for the construction disruption if/when the LRT ever gets built, and — the clincher — a price tag that will be far higher, even in inflation-adjusted dollars, than it would have been, had we built the damn line in advance of development, like sensible cities do.

None of this should be hard to understand, and yet it’s a lesson our political leaders steadfastly refuse to learn. Maybe we should fly the pols over to Hamburg so they can see for themselves what properly planned transit looks like.

top photo by Sacha Sormann (cc); middle photo by Moritz Wellner (cc)

4 comments

“But the lynchpin to the whole exercise was a move that is both wonderfully simple and blindingly obvious from a planning and financial perspective: the city extended the subway directly into the middle of this new area, in advance of redevelopment. Imagine.”

Yet when Line 4, the Sheppard Line, was built by the TTC — mockery. Anyone remember that short Bessarabion Station film? — Just asking

Jeff,

Since you’re asking: that’s some poor logic. Your argument would only make sense if the Sheppard subway line was built in the 60s & 70s when Willowdale and Bayview Village where being built. The subway came almost 40 years after development started in that part of North York.

Just build it already.

This new line should be built at street level on Bay Street (similar to Spadina with separate tracks) It will save multiple millions of dollars AND much faster to complete.