The federal Liberals spent a good chunk of January fixating on foreign students, and how Canadian universities and colleges have become addicted to the full-freight tuition they’re required to pay. Said students, the government contends, have placed an outsized burden on Canada’s buckling housing market. They are also forced to live in abysmal conditions.

The fix came in the form of a two-step: first, a two-year cap on new visas and then, as peripatetic housing minister Sean Fraser announced this week, tweaks to a $15 billion affordable rental construction loan program that would make student residence projects eligible.

Solved? Nope. Toronto’s student housing crisis long pre-dated the current hyper-ventilating, and it will only be confronted, if not solved, when post-secondary institutions and municipalities figure out how to do a far better job of actually providing housing instead of lazily assuming that the tens of thousands of young people who come here to learn will just melt into the city’s broader rental pool, from shared houses to leased condos and cramped basements.

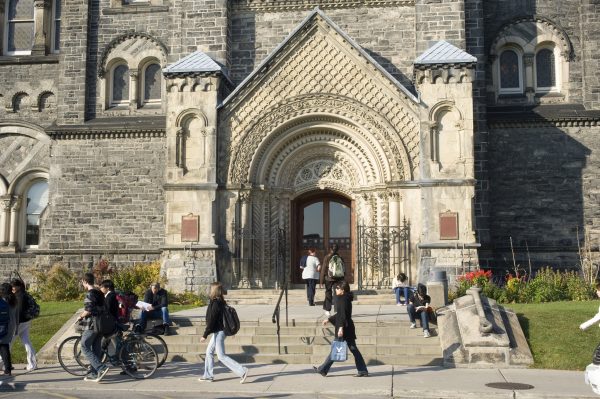

I want to focus on the downtown campuses for the purposes of this discussion because the suburban ones have plenty of land that they can and should develop. While tens of thousands of college and university students attend campuses in the core, the main institutions have for years offered the scantest supply of on-campus residences, typically only to first years.

Since 2004, the University of Toronto and Toronto Metropolitan have each acquired a hotel to convert into student housing, and a handful of newer purpose-built privately-run student housing projects have gone up (e.g. CampusOne’s monolithic tower on College Street, Hoem on Jarvis). The Parkside, a former hotel at Jarvis and Carlton, was converted recently and serves all the downtown campuses.

But even with these additions, the numbers are vanishingly small — a few thousand units — while the traditional source of student housing, shared dwellings, has declined precipitously from years of conversions and gentrification in inner city neighbourhoods. Students live in many of the condos that went up on Bay Street in recent years, but those are either parent-owned or leased for market rates. Anecdotally, many students are stuffed into over-crowded and sub-standard conditions, or just commute. The international students didn’t have the latter option.

Needless to add, this is a constituency with virtually no political profile, especially with local politicians, who don’t care much about this transient population. Which is perplexing, given how important post-secondary education is to the well-being of the city.

Nor have the universities done much better, notwithstanding their endless promotion of student quality of life.

Decades ago, Jane Jacobs bemoaned New York University’s expansionism as it gobbled up Greenwich Village row houses and turned them into residence buildings. U of T seemed to internalize her critique and it would be refreshing to see the university reverse course.

For decades, U of T has been sitting on several blocks of Victorian row houses south-east of Spadina and Bloor — immensely developable, transit-friendly land that should have been transformed into housing for students and faculty years ago, but wasn’t because the local residents association had the wherewithal to kick up a fuss whenever the idea arose.

Last February, U of T and Westbank, the Mirvish Village developer, announced a largely detail-free partnership to building 960,000 sq.-ft of housing, university buildings and retail uses in this quadrant, dubbed The Gateway Project. Media reports at the time mentioned a pair of high-rises, 22 and 29 storeys with about 600 to 700 apartments at the north-west corner, presumably flanking University of Toronto Schools. There’s been little detail since then, and the timelines — construction beginning this year, with a 2028 completion — seem dubious.

Yet it’s not just the university that’s slow-walked this file. The city could set out to partner with the post-secondary institutions and student housing developers to target areas in the vicinity of the St. George campus, to choose but one example, that are crying out for intensification.

Consider the stretch of Spadina Road between Bloor and Dupont, for example — an arterial street lined with largely derelict former mansions that have been carved up into crummy rooming houses for generations. Or Beverley Street south of College, same story. In both cases, with the exception of a stretch of the west side of Spadina, these streets, which are both blessed with deep lots, are zoned for low-rise residential buildings. Yet they are within easy walking distance of several post-secondary institutions, subway stops, amenities, etc. Those archaic zoning restrictions need to be lifted.

The city’s latest planning reforms — up-zoning in neighbourhoods, a re-think of the angular plane requirements in the mid-rise guidelines, the proposed intensification along “major streets” — for the first time in recent memory make this kind of focused redevelopment a possibility.

There’s no reason I can think of that would justify the status quo on either of these streets, yet the status quo is where we’ve been for literally decades, to the detriment of the students who are forced to live in these kinds of buildings.

(The irony is that the next wave of Annex intensification will almost certainly occur two blocks east. With the proposed demolition and redevelopment of a perfectly good rental tower at 145 St. George Street, it seems entirely likely that condo builders will snap up all those mid-rise 1950s/1960s rental apartments north of Bloor, displacing thousands of tenants.)

In the period leading up to the pandemic, there was a good deal of high-minded talk in the city’s post-secondary circles about Toronto’s four universities and the city making common cause to put a dent in a genuine student housing squeeze that was a lot less dire than it is now.

Yet progress has been inexcusably slow, and the campus-adjacent parts of the downtown that are eminently well suited to more and better student housing remain woefully under-zoned and in decline.

This mess isn’t a crisis facing only international students, but it took an international student crisis to wake everybody up. Now, however, it’s up to the city, the post-secondary sector and downtown councillors to pick up the gauntlet that Sean Fraser has thrown at their feet.

One comment

The discussion Loric presents is true. I came to Toronto in the sixties as a student to UofT. I had nightmares to find a decent room to rent. In fact, I begged the superintendent of Tartu College to give me a room while the building was under construction. I accepted it despite the bad smells of carpet glue and early banging of workers.

The biggest barrier is the NIMBY attitude. Not only buildings outside the campus can be built to accommodate students, many of the fraternity buildings on campus house very small number of students. They can be redeveloped while preserving the outside look to keep the vintage look of UofT. These do not have the NIMBY problem. Developing further out sites with a paid bus service to campus can be an option as well. If there is a will, there is a way.