The Housing Series is the product of the last new project Arthur Goss undertook as the City’s Official Photographer. Between March, 1936 and January, 1940, he produced 675 carefully composed photos of housing conditions in designated “blighted” areas of the downtown core. He went on sick leave in February of that year, suffering from progressive muscular atrophy, and died four months later. He had served the city for 49 of his 59 years, having started as an office boy in the Engineer’s Office at ten years of age.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the question of providing adequate housing for low income Torontonians was as warmly debated as it is today, but the problems politicians faced then, and the remedies they proposed, were quite different. Because apartment buildings hardly existed downtown before the Second World War, low income families were forced to occupy small, cheaply built houses, many of which required extensive renovations to be habitable.

Goss had documented individual instances of sub-standard housing for various city departments, but his most complete coverage of the subject had been a group of about 60 images taken between 1912 and 1918 for the Department of Health. His exterior views show houses hidden in blind alleyways or clustered along main streets that were literally falling apart and sinking into the ground.

Throughout his career, Goss had also photographed a wide range of other housing types, including North Toronto farmhouses about to be caught in waves of development, Craftsman Style bungalows spreading over the flat expanses of East York, and the tiny owner-built starter homes that were springing up on the hillsides of Earlscourt.

In 1936, Toronto City Council passed a bylaw requiring landlords to immediately repair sub-standard dwellings or see them demolished. The city was responding to the 1934 Bruce Report on housing commissioned by the provincial government. Goss began his Housing Series three months before the city initiated its program of building inspections under the new bylaw.

Although no administrative records survive, this series was almost certainly undertaken on the authority of the city’s Commissioner of Buildings, Kenneth Gillies. Like Goss, Gillies was a career civil servant who had distinguished himself as an artist. In his earlier role as Assistant City Architect, he had collaborated on the designs of several of the most distinctive public buildings of the interwar period, including the Horse Palace at the CNE and the Water Works complex on Richmond Street West.

The photos in this series show the variety of housing types to be found in the most blighted downtown neighbourhoods. The Second Empire style was common for row housing, while gothic workers’ cottages and saltbox houses appeared both individually and in rows. Shared architectural elements copied from nineteenth century pattern books gave many of the facades an attractive appearance, despite their condition.

The working-class housing in the city had so far been constructed unconstrained by any municipal building code. Goss’s photos of demolitions on Gilead Place reveal some common structural features. Typically there was no basement. The floor plate was suspended a few inches above the ground on sleepers or wooden piles. The framed walls were sheathed in wide boards, to which the outer cladding was attached.

The cladding materials that appear most often are clapboard and roughcast, a type of stucco that has pebbles and stone fragments embedded in its surface. However, finishing walls in roughcast would seem to have gone out of fashion by the 1930s. The series includes numerous views of newly renovated homes with smooth, whitewashed stucco exteriors.

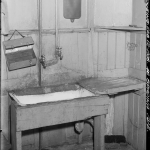

An important element of Goss’s earlier series on slum housing for the Department of Health was environmental portraiture. Adults and children were photographed in the parlours and bedrooms of dwelling whose sad contents were evenly lit by the photographer’s flash. This later series also includes interior photography, but with a different emphasis. The subject here is not people, but what could be euphemistically described as inadequate sanitary facilities. There are enough starkly lit views of horrid toilets and crude kitchen sinks to make the point about the immediate need for improvement.

Documentary photography is a narrative art form, one in which formal perfection is less important than making images work together. Goss, a master of the documentary mode, maintained the narrative thread of this series for 45 months, progressively adding greater depth while respecting the individuality of each subject.

For me, the evocative power of these images derives in part from the way Goss exploited the changing quality of daylight in different seasons. Surprisingly, he took 352 of the photos, more than half the total number, during the winter months. He seemed to have been unfazed by adverse weather, as demonstrated by the photos he took of Roden Place during a December snowstorm.

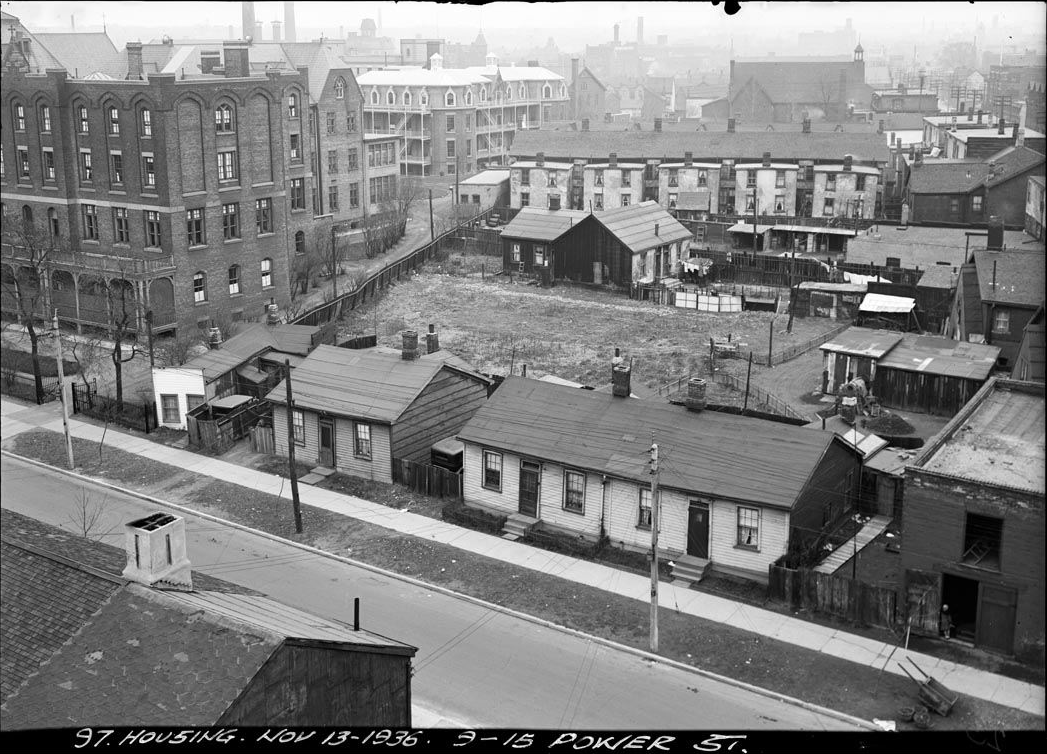

The quality of light in these images gives evidence of the heavy air pollution that plagued Toronto’s downtown when coal was its principal energy source. Living in a working-class neighbourhood meant living with dirty air. In the group of photos Goss took of housing in lower Cabbagetown on November 13, 1936, buildings in the middle distance disappear in a smoggy haze.

The Bruce Report of 1934 had offered a thorough sociological analysis of Toronto’s housing problems a century after the city’s incorporation. Fortunately, Arthur Goss had the artistic skill, and a mandate, to create a lasting visual document of what the report deals with in abstract terms. Through his efforts, we can better imagine what it was like to be marginally housed in Toronto in that grim era.

Between 1947 and 1968, many of the buildings and streets shown in these images were razed to free up land for the Regent Park and Alexandra Park housing projects, and our new City Hall. However, fragments of the old urban fabric remain, for example, the row houses at 1-15 Percy Street in lower Cabbagetown, which first appeared on a Goad’s Insurance map in 1890. When Goss photographed their Second Empire facades in late afternoon on March 22, 1938, they seemed to be awaiting demolition. Instead, they were renovated and remain in excellent condition today.

See other articles in this series:

- The urban photography of Arthur Goss, Part 1: : Career and technique

- The urban photography of Arthur Goss, Part 3: Parks and Recreation, 1913-1940

- The urban photography of Arthur Goss, part 4: Toronto Water Works, 1910-1939

Click on any image below to launch the photogallery

Housing No. 7, June 4, 1936

52-54 Best Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0007

Housing No. 7, June 4, 1936

52-54 Best Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0007

Housing No. 420, Nov. 21, 1938

10-12 Crocker Ave.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0420

Housing No. 420, Nov. 21, 1938

10-12 Crocker Ave.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0420

Housing No. 30, July. 29, 1936

63-65 Mitchell Ave.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0030

Housing No. 30, July. 29, 1936

63-65 Mitchell Ave.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0030

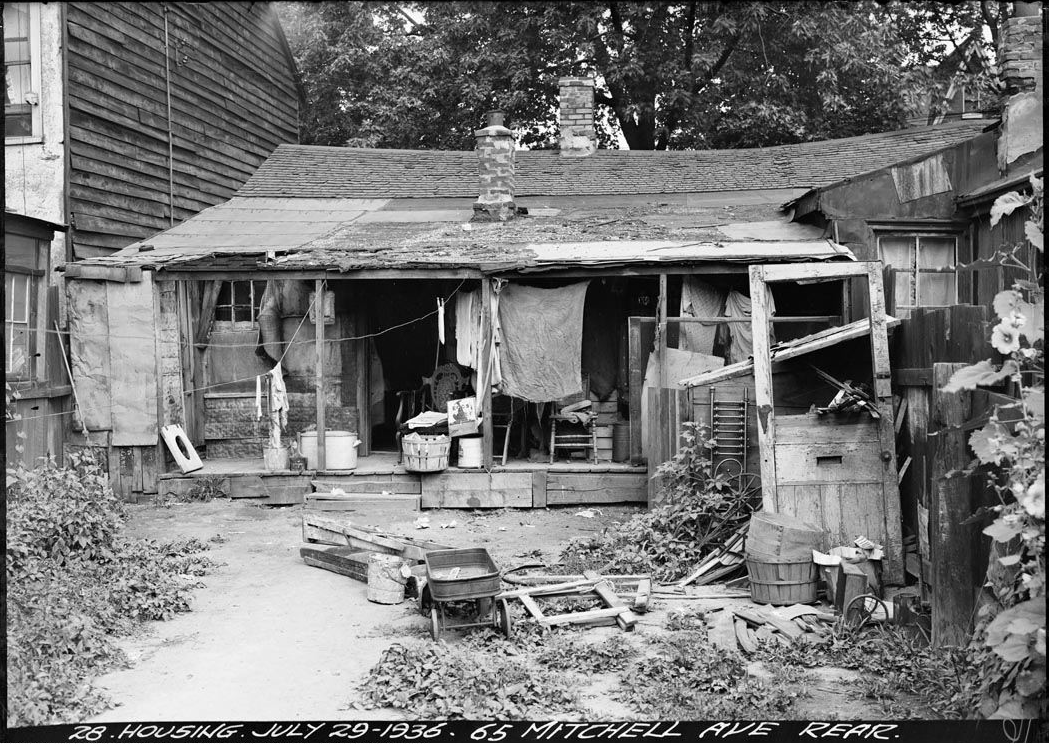

Housing No. 28, July. 29, 1936

63-65 Mitchell Ave. Rear

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0028

Housing No. 28, July. 29, 1936

63-65 Mitchell Ave. Rear

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0028

Housing No. 35, July 30, 1936

96-112 Tecumseth St.

City of Toronto Archi ves, s0372-ss0033-it0035

Housing No. 35, July 30, 1936

96-112 Tecumseth St.

City of Toronto Archi ves, s0372-ss0033-it0035

Housing No. 62, Sept. 23, 1936

Gilead Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0062

Housing No. 62, Sept. 23, 1936

Gilead Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0062

Housing No. 64, Sept. 23, 1936

Rear W. S. Gilead Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0064

Housing No. 64, Sept. 23, 1936

Rear W. S. Gilead Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0064

Housing No. 98, Nov. 26, 1936

Roden Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0098

Housing No. 98, Nov. 26, 1936

Roden Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0098

Housing No. 468, Dec. 21, 1938

17-37 Roden Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0468

Housing No. 468, Dec. 21, 1938

17-37 Roden Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0468

Housing No. 357, May 5, 1938

Water Supply for 4 Houses, Rear 73 Stafford St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0357

Housing No. 357, May 5, 1938

Water Supply for 4 Houses, Rear 73 Stafford St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0357

Housing No. 358, May 5, 1938

Rear, 75 Stafford Sr.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0358

Housing No. 358, May 5, 1938

Rear, 75 Stafford Sr.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0358

Housing No. 132, Feb. 26, 1937

2-6. Arnold Ave.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0132

Housing No. 132, Feb. 26, 1937

2-6. Arnold Ave.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0132

Housing No. 126, Feb. 26, 1937

284-288 Parliament St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it06

Housing No. 126, Feb. 26, 1937

284-288 Parliament St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it06

Housing No. 137, Feb. 26, 1937

15-17 Centre Ave.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0137

Housing No. 137, Feb. 26, 1937

15-17 Centre Ave.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0137

Housing No. 164, March 30, 1937

4-6 Foster Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0164

Housing No. 164, March 30, 1937

4-6 Foster Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0164

Housing No. 461, Dec. 16, 1938

112-114 Morse St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0461

Housing No. 461, Dec. 16, 1938

112-114 Morse St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0461

Housing No. 97, Nov. 13, 1936

9-15 Power Street

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0097

Housing No. 97, Nov. 13, 1936

9-15 Power Street

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0097

Housing No. 94, Nov. 13, 1936

1-3 Turner’s Lane

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0094

Housing No. 94, Nov. 13, 1936

1-3 Turner’s Lane

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0094

Housing No. 189, April 12, 1937

346-356 Gilead Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0189

Housing No. 189, April 12, 1937

346-356 Gilead Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0189

Housing No. 225, Sept. 9, 1937

336 Gilead Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0225

Housing No. 225, Sept. 9, 1937

336 Gilead Place

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0225

Housing No. 374, April 12, 1937

153-157 River Street

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0374

Housing No. 374, April 12, 1937

153-157 River Street

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0374

Housing No. 446, Dec. 2, 1938

2-16 St. David St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0446

Housing No. 446, Dec. 2, 1938

2-16 St. David St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0446

Housing No. 608, Sept. 28, 1939

2-16 St. David St., See 446

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0608

Housing No. 608, Sept. 28, 1939

2-16 St. David St., See 446

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0608

Housing No. 376, Sept. 9, 1938

23 Lewis St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0376

Housing No. 376, Sept. 9, 1938

23 Lewis St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0376

Housing No. 518, March 29, 1939

3 Milan St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0518

Housing No. 518, March 29, 1939

3 Milan St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0518

Housing No. 390, Sept. 15, 1938

16 Willis St., See 521

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0390

Housing No. 390, Sept. 15, 1938

16 Willis St., See 521

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0390

Housing No. 302, Feb 12, 1938

48 Spadina Ave.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0302

Housing No. 302, Feb 12, 1938

48 Spadina Ave.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0302

Housing No. 633, Nov. 22, 1939

88 Vanauley St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0633

Housing No. 633, Nov. 22, 1939

88 Vanauley St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0633

Housing No. 635, Nov. 25, 1939

88 Vanauley St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0635

Housing No. 635, Nov. 25, 1939

88 Vanauley St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0635

Housing No. 604, Sept. 23, 1939

30 Ryerson Ave., See 561

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0604

Housing No. 604, Sept. 23, 1939

30 Ryerson Ave., See 561

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0604

Housing No. 171, April 8 1937

56-58 Elizabeth St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0171

Housing No. 171, April 8 1937

56-58 Elizabeth St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0171

Housing No. 173, April 8 1937

701/2-74 Elizabeth St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0173

Housing No. 173, April 8 1937

701/2-74 Elizabeth St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0173

Housing No. 675, Jan. 31, 1940

591-595 Queen West

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0675

Housing No. 675, Jan. 31, 1940

591-595 Queen West

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0675

Housing No. 328, March 22, 1938

1-15 Percy St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0328

Housing No. 328, March 22, 1938

1-15 Percy St.

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0033-it0328

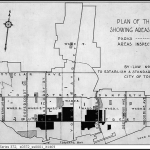

Architects No. 1469, April 27,1939

Plan of the City Showing Areas Inspected

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0001-it1469

Architects No. 1469, April 27,1939

Plan of the City Showing Areas Inspected

City of Toronto Archives, s0372-ss0001-it1469