This column introduces our new cycling columnist, Sabat Ismail, who will be contributing insights into cycling in Toronto. Sabat Ismail is an urban planner and artist based in Toronto.

My fondest summer memories have always included me on a bike: biking down hills, passing by a chorus of chirping birds, watching rabbits scurry away as I near, discovering parts of my community that I had never seen – or that I never had the chance to connect with in the unique way that you can on a bike.

Even better than biking on my own has been the opportunity to connect with and support others through cycling education. Specifically, supporting youth across Toronto to bike, whether through providing bike repair, instruction on how to ride a bike, cycling tips, or delighting in seeing students build friendships and memories through bicycling.

My first foray into cycling education was as an educator with the Bike to School Project. My colleagues and I got the chance to work across Toronto, helping to encourage youth to cycle safely. I worked with colleagues to organize bike rodeos, co-present at assemblies, deliver lessons on safe cycling, and give out copious amounts of bike stickers.

But as I worked in working-class communities and I looked out into gymnasiums full of racialized youth, I could not shake the feeling that I was in a sense telling these children that once they were equipped with cycling skills and gear, they would be safe to ride in their communities. That, once they learnt the rules of the road and adhered to them, they would be safe. That, once they are over the age of 14, they would have to ride on the road, and that they would be okay. Just wearing a helmet and locking their bikes in a particular way would be sufficient.

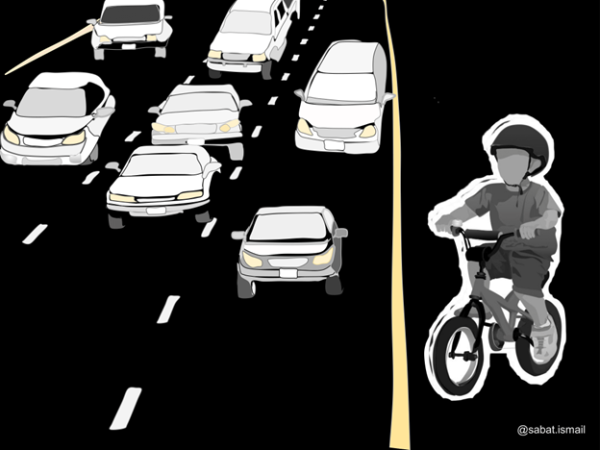

I found myself thinking, ‘Who am I to tell these children that they would be safe cycling?’ I couldn’t help but consider the multifaceted ways in which people of colour, who predominate in these neighbourhoods, experience a lack of safety. I worry about my younger sibling’s safety while simply walking and navigating public space, let alone while biking on the street in a car-dominant community.

I can’t look at my family members, many of whom are Black hijabis, and encourage them to ride when I know that they are exposed to an acute sense of danger in their day-to-day lives because of how they are regarded in the world. I cannot assure them that they will be safe on a bike, so how could I offer that to these children?

As I rode into the city’s inner suburbs, despite my freshly minted CAN BIKE certification and my many years of cycling, I felt unsafe taking up space on busy streets and I felt uncomfortable illegally riding on those often-busy inner suburban sidewalks. For our learn-to-ride classes, we would usually scope out the neighbourhood in advance, so we could find a place to conclude our lessons with a group ride. At one school on Eglinton West, my colleagues and I scoped out the area and found it almost impossible to find a place where we felt confident taking these high schoolers. As I rode up to the school and neared Eglinton West, I was constantly looking over my shoulder and holding my breath. I made sure to not fully turn my head to look, because I did not want the driver behind me to know how afraid I was of him pushing me off the road, or worse.

These experiences usually struck a stark contrast to what I saw in the whiter, wealthier neighbourhoods where we taught. These were communities where the schools and their surroundings were much more aesthetically pleasing, where the streets were calmer, and more children had bikes.

A recurring joke amongst us educators as we worked in those neighbourhoods was that the kids we were teaching (who would undoubtedly soon grow out of their bikes) had nicer bikes than us. I observed that in lower-income neighbourhoods children were less likely to have bikes for the event, and some of their classmates shared bikes as they took their turns completing the cycling exercises.

In Thorncliffe Park and Flemingdon Park, a working-class neighbourhood, I noticed an interesting, related phenomenon. I saw kids at the local community bike shop, where we provided youth with free bike services, with one bike to share with an entire family. Just one person getting access to a bike could mean providing others in their immediate family the ability to ride. I assume that, just like my experiences and those of other immigrant and refugee families, a working bike that someone grew out of would be re-housed amongst family or community.

Initially, I found the way that families in Flemo and Thorncliffe shared bikes lovely to see – how families shared with each another, facilitating connection and building meaningful community. At the time, I saw it as a demonstration of how racialized and working-class communities value collectivity. In retrospect, I recognize this phenomena was in part a result of economic injustice, which is of course intimately intertwined with racial injustice. These hand-me-downs – or as we say in Harari, hajees-wa-harees – were an unconscious act of defiance of capitalism, consumerism, and traditional “Western” logics of ownership, but also a by-product of the scarcity that often confronts our communities.

A colleague recounted an experience from a school he and others were teaching at in Parkdale, where one child’s father had been struck and killed while on his bike. He described how the students at the school almost entirely had no bikes for the workshop – because the resounding impact of his death had a resounding impact on families at the school – and that he and the other educators had to try and make do.

Too often, North American discourses on cycling question why racialized communities do not cycle, with assumptions revolving around “cultural” attitudes. This is a misguided line of reasoning for many reasons. For one thing, the very basis of the discussion is false: most cyclists in North America are people of colour, and data from the US shows that racialized people are the fastest-growing demographic of cyclists. Additionally, it places the blame on marginalized communities, rather than considering the ongoing neglect and chronic under-resourcing of our communities. Furthermore, we have limited social capital or spheres of influence to mobilize to even try to bring changes to our communities, whether to dismantle systems of oppression that adversely impact us or to refashion the streetscape.

Our cities reflect our society. Inequality and inequity, divided along race, class, and gendered lines, reflect us. It reflects our social realities, and whose safety we prioritize. Who has access to good-quality bikes, adequate transportation infrastructure, safe streets to walk, roll and live on is a by-product of political choices and systemic inequality.

Most of the kids in these inner suburban communities that I had the pleasure of working in had positive connections with bikes. They had fond memories of riding bikes, like many of us do. But they also confronted neighbourhoods that lacked the infrastructure to allow them to navigate their communities with dignity and safety. If this lack of access and safety is not addressed, it will inevitably endanger them and dissuade many of them from riding in, and uniquely connecting with, their communities altogether.

I loved my job, and accessing free cycling education programming has been a personally invaluable and transformative opportunity, but we must grapple with the nuances and the complexities of safety. Children playing, being active, and connecting with their communities is invaluable, but I worry about the streets we are inviting them into.

Image by Sabat Ismail