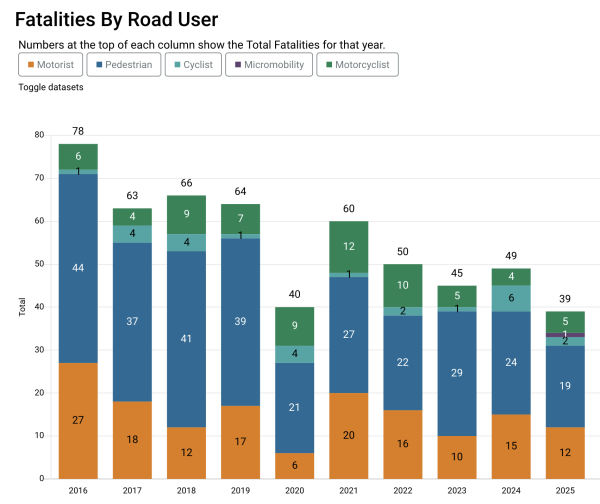

The city’s Vision Zero team released its 2025 data yesterday and the trend lines are encouraging: overall, the number of traffic-related deaths — 39 for last year — is down from the three previous years, and there’s clear evidence of improvement over the decade since Toronto adopted the Scandinavian safety strategy.

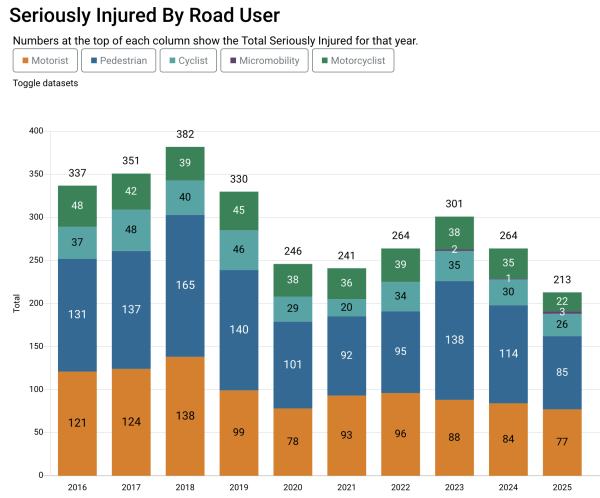

In particular, annual pedestrian deaths have declined steadily from 44 (2016) to 19 (2025), with the exception of the asterisk year — 2020, when everything dropped a lot because of the pandemic. The number of serious injuries has also dropped consistently, from a high point of 165 in 2018 to 85 last year — an impressive improvement.

The City points to all sorts of Vision Zero enhancements added since 2016 — almost 1200 new community safety zones (reduced speed limits, higher fines), 649 new school safety zones, 224 new traffic signals and crosswalks, and almost 1,700 pedestrian head-start traffic signals.

Also worth noting that deaths and serious injuries to drivers has also fallen, pretty much in lock-step with the pedestrian figures. The learning: that if you’re behind the wheel, those reduced speed limits and other calming measures are making you safer.

What hasn’t changed in a discernible pattern is cyclist deaths and serious injuries. There was one death in 2016, and then several years with higher fatalities — 2017, 2018 and 2020 (four all years), 2024 (six). For the remaining intervals, one or two annually, including one for 2025. Serious injuries have fallen since 2023, from 35 to 26, after climbing for four years straight. These numbers, for the record, are still below the levels seen in the mid-2010s, when there were an average of about 43 serious cyclist injuries per year.

So here are two uncomfortable questions about what these data say or don’t say about the state of the city’s roads:

- Has the worsening post-2020 gridlock, which forces cars and trucks to move more slowly (and therefore less lethally), created what is, in effect, a city-wide calming effect, and if so, could Mayor Olivia Chow’s campaign to relieve congestion by appointing a traffic czar, Andrew Posluns, potentially make the city less safe for pedestrians and cyclists?

- Why haven’t we seen similarly steady improvements in cycling safety indicators over a decade during which the city made huge advances in the construction of dedicated and segregated bike lanes on major arterials as well as the creation of north-south routes through side-streets using contra-flow lanes, parking restrictions and so on?

As a study published in 2024 in BMJ’s Injury Prevention Journal found, the number of police-reported incidents in which cyclists were killed or seriously injured fell between 2016 and 2021, from 38 to 21, as did the volume of collisions involving motor vehicles. But hospitalizations and ER visits didn’t change much over the same period, at least in part due to the increased amount of cycling activity during the pandemic. The same study found that cycling injuries were “severely under-represented” in police data, particularly those not involving a vehicle.

Let’s first go back to question 1, and just begin with the obvious — to me, anyway — limitations on what Posluns can actually do. He may be able to find ways to force or incent developers to prevent their construction sites from spilling into lanes of traffic. But whether he’s got either the budget or the bureaucratic clout to tackle the really gnarly issues — banning street parking on streetcar routes, adding more transit priority signals, boosting the TTC’s operating budget and fares so it can add more service, etc. — is by no means clear. And there’s not a thing he can do to get the Ontario Line finished more quickly.

Now, about pedestrian safety and congestion. When cars are able to move faster — presumably, the goal of a traffic czar — they simply pose a greater/graver threat to pedestrians. Changes that increase speeds will severely test all the Vision Zero measures the city has deployed in the past few years, especially now that Queen’s Park has banned speeding cameras.

Posluns is not a newbee so he certainly understands that part of what he’s expected to do is advocate for more and faster surface transit. But here again, there are very challenging trade-offs.

I am at a loss, for example, to understand why the city allows parking on crawling streetcar lines that face endless delays and re-routings due to subway construction. Local councillors and businesses will shout bloody murder if the city even temporarily halts street parking. On the other hand, such a move might allow both streetcars and vehicular traffic move faster. But would this kind of fix make clogged arterials like King, Queen, Dundas and College less safe for pedestrians and cyclists? And if that’s a foreseeable outcome, what steps will the city take to mitigate that risk?

The point is that the Posluns needs to itemize the pros and cons of any proposed solution and then explain to council and Torontonians why they won’t produce more injury and death in the name of getting to work or the gym five minutes faster.

Now on to question 2. The issue of preventable death and injury was front and centre in the Cycling Toronto lawsuit against the Ford government’s vindictive and muddle-headed campaign to uproot the city’s bike infrastructure. Lawyers for the plaintiffs introduced extensive empirical and peer-reviewed analysis showing that the removal of segregated bike lanes will lead to more collisions, deaths and injuries. They advanced all this evidence to support their argument that the Ford government’s move violates Section 7 of the Charter, which guarantees life, liberty and security of the person. Last July, the trial judge agreed and the government has appealed.

No employee of the city, even one with a lofty title like traffic czar, will recommend that council defy the provincial government, which holds all the jurisdictional cards, especially while the appeal is pending.

But as with question 1, Posluns needs to be thinking about whether his solutions involve trade-offs that inadvertently make it more dangerous to cycle (or walk). I don’t think his task is necessarily a zero-sum game, but I can easily imagine how it devolves into one.

What’s more, the entire cycling infrastructure group within the city’s transportation division should also take this interregnum — i.e., with the appeal pending — to dig more deeply into the causes of cycling collisions and injuries, which remain unacceptably high.

Here again: more uncomfortable questions: Do we need actual and enforced restrictions on the fast-moving e-bikes and scooters that seem to be crowding out cyclists, or would it help to widen existing lanes? Are there specific places on the bike lane network that are demonstrably dangerous, and if so, what is the city doing to remedy these hot-spots?

Council has named a traffic czar just in time for a municipal election. But Poslun’s real task, in my view, is to look beyond his titular mandate, a task that should begin with a daily reminder that when vehicle traffic moves more briskly, everyone’s safety (including drivers) becomes that much more compromised.

photo by courtesy of City Clock (CC)

One comment

The introduction of congestion tax in NYC last year provides a natural experiment that could show whether speeding up vehicle speeds leads to increased danger for bicyclists and pedestrians. Has that been investigated.