There was an interesting article in the Star recently (with a misleading headline) about how Chicago’s chief financial officer arranged leases on profitable city-owned infrastructure with private companies, and so raised billions of dollars of capital for the city. These assets included some parking garages, all the city’s parking meters, and the Chicago Skyway, a 7.8 mile toll bridge and road connecting two expressways.

Leasing is certainly a better option than selling valuable city assets outright. The city raises needed money, and then, eventually, the assets return to the city and it can either start managing them again and get the revenue directly, or re-lease them.

It’s not ideal, though. Leases tend to be very long term (e.g. 99 years), so it’s not much different from privatization in the short term. And it might not make a lot of economic sense to sell or lease an asset that makes good money (such as Toronto Hydro), as economist Jim Stanford explains in the article:

“Think of Toronto Hydro,” said Stanford. “The city typically earns an annual profit of about 10 per cent on its equity investment. Some of that (but not all) is paid to the city as a cash dividend; but even the profits that are retained inside Toronto Hydro are still new wealth for the City.

“If you sell off an asset that earns 10 per cent, in order to pay down debt (or avoid new debt, which is equivalent) on which you pay 5 or 6 per cent interest, have you made a good decision? Obviously not.

“Your balance sheet is no stronger: debt is lower, but so are your assets.”

On the other hand, reading the article (especially the mention of the Skyway), I wondered whether it might make a sense to set up a lease on city assets that don’t earn any revenue but have revenue-generating potential, with a private company that is able to earn revenue with them. In return, the city could get a big dose of capital funding. I am thinking of the Don Valley Parkway and the Gardiner Expressway, which were handed over to the city to manage (and pay for) as part of the Harris government’s downloading.

Both highways cost the city money to maintain, and provide a significant benefit for their users (much faster travel times) for free and, as a result, are heavily over-used (reducing the user benefit as a result of congestion). They seem like obvious candidates for user-payments through tolling, but this option gets huge resistance because it looks like a simple cash grab by the city, and the alternative travel options (the subway lines) are already at or near capacity. The result is a Catch-22: the City doesn’t want to establish tolls without alternative transit routes, but it can’t build alternative transit routes because it doesn’t have the capital funding.

But setting up a lease on these highways with a private company that would install tolls, in return for a large capital injection for the City, might get around some of these obstacles — if the money was then used directly to fund the construction of transit routes that provide alternative travel options. These alternatives would be the Don Mills LRT, the Waterfront West LRT, and especially the Downtown Relief Line, which would both continue the Don Mills LRT to downtown, and link Dundas West Station to downtown for commuters coming in from Etobicoke and places west. Clever people in the financial district could probably structure it so that the city got access to some capital right away, but the tolls didn’t kick in until some time later — giving enough time and money to at least get started on building the alternative transit routes before tolling began. As many municipal referendums in the US have shown, taxpayers are more willing to pay new user fees or taxes for a tangible asset than for general municipal operations.

The highway 407 experience has shown there would have to be some kind of control over the toll rates, but that can be done with a good contract. Many private companies would be more than happy with the very predictable revenue stream they would get from the arrangement.

I’m not a number cruncher, and numbers would need crunching to see how viable this option is and how much the city would get. And no doubt there are other complicating issues to consider — perhaps our readers can further parse some of the potential complications and benefits. But it might be worth investigating as a potentially more politically viable, and possibly financially viable, way of funding much-needed new transit lines in the city through road pricing.

Note: I wrote this post before I saw today’s headline in the Toronto Star re. Smitherman and privatization, which seems to be more about contracting out services.

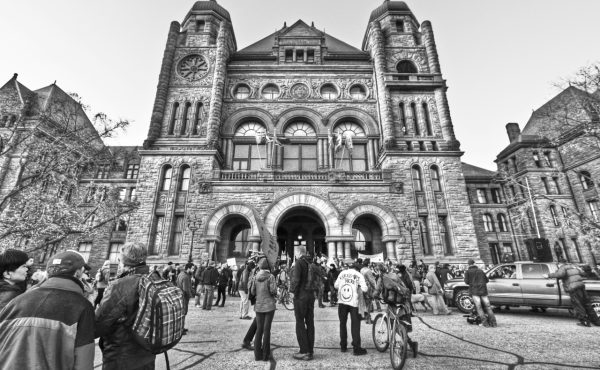

Photo by dougtone

32 comments

Folks need to understand better the difference between selling or leasing public assets on the one hand, and contracting with private companies to private public services. And then they need to understand that privatizing/leasing is pointless at best.

Privatizing an asset like a toll highway or Toronto Hydro is just a way to convert a future stream of income (tolls, fees, taxes) into an upfront payment. It does not create value out of thin air, no matter what the Bay St. types will tell you! In fact, it is almost exactly the same as borrowing more money by issuing bonds – except that Toronto bond issuing is regulated and limited by the province, whereas its asset sales would not be. But the borrowing limit could simply be relaxed by the province.

On the other hand, contracting out could be a good idea. In some cases private companies could do some things more efficiently, or they could transfer new ideas to the city. It also could be a better way to deal with the risk of public sector strikes (even if contractors are unionized) – a much better way than the trial balloon floated last week by McGuinty/Caplan.

The best idea raised in this post is charging tolls on city-owned freeways. But that could be done without selling or contracting out the assets. Let’s have a discussion of tolls without confusing matters with the bugbear of bad privatizations like 407 ETR.

All the reasons you need to see why this is a terrible idea are right in your post – the 407. Which is the most expensive tollway in North America.

You quickly brush that off with an off-hand “oh, a better contract will fix that,” but private enterprise is in the business to MAKE MONEY, not provide essential services. Seeing as the DVP and Gardiner are the only highways in and out of the actual city of Toronto, a private company would essentially have a monopoly on automotive travel.

You’d had some bad ideas before but this is easily the worst one yet.

Sounds like a good idea. Will still face a lot of political opposition for sure, but more plausible than simply start tolling.

The one problem: The city has a nasty habit of using one-time money to cover current shortfalls. This isn’t even a dig at Miller or his allies with the current situation. Lastman did the same thing (raiding rainy day funds) to keep taxes the same for years.

A better situation would be something along the lines of: build us a subway along Queen st. and you get the Gardiner for 99 years.

There are incentives to keep in mind, though. The 407 is a wonderful highway to drive on. Unless there’s an accident, traffic flows freely because they keep the prices at a level that allows that. They’ve added lanes, they plow it religiously, and pour money into maintaining the roads. What happens in the last 10 years of the lease, though? There’s no incentive to maintain the highway if they won’t get a return. Will the province get a crappy highway back in the end? This is even more dangerous with the elevated Gardiner.

This post is spot on and it’s ironic that Jim Stanford opened the door by pointing to return on investment. If the City of Toronto is getting 10% ROI from TH, assuming JS has his numbers correct, that’s terrific (except if you’re a TH billpayer) but we have to look at the assets which don’t produce a decent ROI (which you can define as either of “we could stick it in the bank and get more in interest” or “we could pay off debt/decline to raise more debt and save more in interest” and which are not part of social mandates.

It’s interesting to see Shelley Carroll bring forward a budget which proposes to lease out the ski hills and I wonder if this is a precursor to a mayoral platform which would lease out a lot of other recreational facilities like the golf courses which people are used to seeing provided by the private sector, or at least the ones that Don Valley’s fees subsidise.

With respect to the Gardiner/DVP and its connectors, the notion of removing some of it within the lease period would likely be ruled out, so that should be borne in mind before flogging it off.

I don’t agree with the city leasing these, they should just Toll them up themselves, and take the money.

The driving distance from Eglinton & Don Mills to Spadina & Richmond is, according to Google Maps, 15.4km. Let’s say for the sake of argument you are going to built 15km of subway.

Current subway costs are at least $300m/km. (The 6.8km Richmond Hill extension is projected to cost on the order of $2.3b.) This means that the DRL will set us back at least $4.5b.

One way or another, we need to finance this long term probably at a cost somewhere around 5% (before allowing for any profit that the private owner of the mortgaged DVP might want to make). This requires an annual payment stream of $225m.

Motorists scream when we talk about revenue tools that might bring in tens of millions per year, let alone hundreds. If they are going to pay for the DRL, then let the cost be spread over all road users so that, by tolling the highways, you don’t create a spillover effect onto local streets.

Oh yes, there’s the small issue of peak oil. Where does the toll revenue come from when people can’t afford to put gas in their cars?

This is creative accounting 101.

The really high tolls on the 407 are a feature, not a bug. SNC Lavalin (the lead company in the 407 consortium) can ignore the car-driver lobby. Most politicians cannot withstand political pressure exerted by car owners.

Good idea, although this mainly comes down to political will – regardless of a private sector partner or not, councilors will still need the guts to toll.

Put in the context of the region, the mayor says its an economic death wish – we need to toll the 400-series roads at the same time otherwise it is effectively a congestion charge and a hindrance on Toronto businesses. At a time when businesses are already looking for greener pastures in the burbs and the city is reducing the property tax burden on businesses, a DVP/Gardiner Toll can’t be the solution.

Finally, it also comes down to the question of who can better maintain the asset, the city or a private sector partner?

Except from Highway 427 to the Humber River on the Gardiner, both the DVP and the Gardiner were built by and maintained by Metro.

The rather ridiculous highway downloadings of 1997 and 1998 (whose legacy is an unnavigatable road system province-wide) by Harris left Toronto relatively unscathed – only Highway 27, the QEW east of the 27 and less than 2 kilometres of Highway 2A were dumped on the city, but the downloaded QEW was in horrible shape.

That said, while I like the idea above, this would easily be called out as back-door road tolls. The only benefit over direct tolling is that it unlocks capital funds up-front.

Great, as if Toronto needs anymore help in becoming the unemployment capital of Ontario/Canada. For all of those thinking that there will be a net benefit from this for the city by getting revenue from non residents, keep in mind that traffic flows are now reversed. The Gardiner’s AM outflow is greater than its inflow.

Downtown wards 20,27 and 28 combined, the stats show an alarming trend. Between 1989 and 2004 these wards combined had lost 26,404 employment positions (Toronto employment survey). Between 1991 and 2001 the percentage of residents in these wards whom commuted outside of the city to work increased by 14.3%.

one note – the gardiner and DVP were never dowloaded to the city from the province except for a small portion of the gardiner west of the humber river to the 427. this portion should be uploaded (and i would argue the entire dvp and gardiner)to the province post haste.

The Urbanophile blog did a interesting series on the principles of privatization, using the Chicago Skyway lease as one of the key examples. Worth a read if you’re interested in the topic.

See: http://www.urbanophile.com/2009/10/22/principles-of-privatization-part-1-taxonomy-of-transactions/

http://www.urbanophile.com/2009/10/29/principles-of-privatization-part-2-value-levers/

http://www.urbanophile.com/2009/11/07/principles-of-privatization-part-3-uses-of-funds/

http://www.urbanophile.com/2009/11/15/principles-of-privatization-part-4-guidelines-for-action/

In related news, there is an ongoing provincial-municipal review regarding roads and bridges that is evaluating responsibilities and costs.

Despite the provincial deficit, a long-term plan (starting with cost-sharing and eventually a full upload) for the DVP and Gardiner will undoubtedly be an ask from the city.

Steve Munro: “Motorists scream when we talk about revenue tools that might bring in tens of millions per year, let alone hundreds.” Revenue tools like vehicle registration, which taxes place of residence and not usage? Can’t see why people wouldn’t resent that.

If vehicle usage was to fall dramatically as a result of tolls, that just provides an excuse to get rid of some or all of the Gardiner and develop land currently blighted by viaducts, as is now being floated for the Dunsmuir and Georgia Viaducts in Vancouver. This case would have to be built into the toll lease though.

It’s worth noting that Translink in the Vancouver Region doesn’t just run transit but roads and bridges too. Perhaps Metrolinx should assume responsibility, since it’s looking to take charge of transit within the city by having ownership of the Transit City lines?

“It also could be a better way to deal with the risk of public sector strikes”

Wouldn’t contracting out transit be a worse way to deal public sector strikes, because the city would no longer have any control over the negotiation process, so a strike could drag on longer then the city would find acceptable.

but what if pigs did fly? see — then, so, well that means going veggie is good. and privatization is good, too. i can’t wait.

@Glen

I agree that Toronto needs to take action to attract more employment to within the city limits. And that will need to include tax changes and more supportive policies and regulation, as well as the depletion of cheap suburban land in the surrounding municipalities.

But your claim re: traffic on the Gardiner smells of sophistry. Inbound and outbound rush hour flow may be about equal, but that ignores the Lakeshore GO line which carries tens of thousands of people more than the Gardiner does, the vast majority inbound.

“Wouldn’t contracting out transit be a worse way to deal public sector strikes, because the city would no longer have any control over the negotiation process, so a strike could drag on longer then the city would find acceptable.”

When services are contracted out it is common for firms bidding to have a collective agreement that will be in force for the life of the contract. Think of the garbage strikes that happen in Toronto but not elsewhere in the GTA (where contracting out is the norm).

Unions are good. Competition is good too.

Since the end result of leasing would be tolls, it’s reasonable to assume there would be a lot of hysteria from the inner burbs about the “war on the car.” So why not just keep the DVP and Gardiner in public hands and toll them directly? That way we could at least retain the option of demolishing them between the DVP’s Richmond/Adelaide exit and the Gardiner’s Yonge/York exit. Either way we would also get to enjoy the usual hot air from Ford, Wong & Co.

John,

I was not talking about aggregate flows into the core. I was specifically looking at the incidence of the revenue.

Yes the stats I provided do not look at GO ridership. They also ignore the thousands of other routes that people can use to leave or enter the city. Rest assured that if Gardiner outbound AM traffic is increasing so are all the other routes.

I would also like to clarify your remark about ‘cheap suburban land’ as a driving force for employment growth outside of the city. In a report done on behalf of the city of Toronto, Hemson consulting found that land for office development in Mississauga (ACC) was 55% more expensive compared to the Consumers Rd. area in Toronto. Despite the much lower cost for land, and having no development fees, compared to $800,000 for a mid rise office in Mississauga, building in Toronto is not feasible (with some exception). The 50 acre former Kodak site was sold for 19.5 million, 390,000 per acre, how much cheaper can you get?

Yes the reason is taxes. I mean, if Dukes is having difficulties building retail space in one of the most vibrant areas, on land that they already own, with a chunk of insurance money and a below market assessment value, then something is terribly wrong.

“If you sell off an asset that earns 10 per cent, in order to pay down debt (or avoid new debt, which is equivalent) on which you pay 5 or 6 per cent interest, have you made a good decision? Obviously not.”

Wow… Jim Stanford may be an economist, but this is a completely incorrect statement that bastardizes financial theory.

I still don’t see what is so awful about the 407. I can accept the argument that our lease price (and it is leased, not “sold”) was lower than it could have been,and should be remembered as such, but these arguments that the 407 was the infrastructure equivalent of Battlefield Earth are overblown.

It cost us a bit over 1 1/2 billion to build, we sold it for over three and then they invested an extra billion for a bit over 400 lane-kms. We probably could have sold it for a bit more, but “we can do better” isn’t the same argument as “we got screwed.”

Its also true that, in a sense, the high-ish tolls (they aren’t abnormally so, some roads in Sydney are about 4x higher)are a benefit. Just about any transport economist will tell you the major problem with our current network is providing road space @ a marginal cost of zero encourages overuse (congestion) and inefficiency. The 407’s ability to use prices to maximize traffic throughput is a major advantage, and one I simply don’t believe a public toll road could offer. If the 407 corp all of a sudden raised peak tolls to ~1$/km or something, then maybe there’d be an issue. I don’t really see how ~20c/km is gouging.

p.s. While tolls aren’t regulated, usage levels are. The contract requires the 407 to maintain a certain usage threshold or pay fines. In effect, this limits the ability of the 407 to raise prices and discourage usage excessively. I’m not sure what the threshold is, but rather than regulating prices on toll roads directly to prevent gouging, it may be more effective to require usage levels reasonable for a roadways given design capacity.

I’m not exactly sure what usage rates of the DVP/Gardiner are at the moment. I found that 200k riders use the Gardiner west of downtown, so I’m just going to use that. Average trip cost on the 407 is ~4$, so I used that number. Over a 75 year lease, discounted at 10%, that should give us a npv of about 4.1 billion. God knows that’s incredibly simplistic and back of the envelope given I don’t even have decent ridership figures.

An alternative way to look at it would be comparative. Wiki says “today the [407] would be valued at over 10b.” I’m not sure where that came from, but assuming it isn’t just a lunatic, the 407 has ridership of about 400k/day. Assuming revenue/costs per trip would be similar, and the Gardiner/DVP gets 200k/day, a rough valuation would be 5b.

So, on an educated guess basis, I’d assumed that between 4-5b may be an appropriate sale price. Obviously youd want more research than this, but I think the 4-5b range is appropriate for guesstimations.

The main problem with 407 is the billing system, the alleged inaccuracy thereof and the tactics used to get the revenue. However, the Government of Ontario could solve that by requiring ETR to separate billing into an operation Ontario has more scrutiny of as part of the negotiations to extend 407 to 115/35.

Selling or leasing infrastructure to the private sector is rarely a good deal. The city typically receives significantly less from the private company than if it were to simply levy tolls itself and then issue debt to finance capital spending which is to be repaid by toll revenues in future years. After all, the city can borrow at lower interest rates than the private sector, and the private sector has to make a profit.

Re: David’s comment – “I still don’t see what is so awful about the 407…”

Really? I guess some people just think it’s OK that the public sector essentially finance initiatives that amount to little more than gravy trains for a private consortium. But this kind of endeavour makes no sense whatsoever whether from a public revenue or an efficiency standpoint. Leaving aside the issue of whether tolls are or are not appropriate, if there are going to be tolls on any section of road, these monies should be adding to public revenues rather than padding the profits of private interests who were allowed to buy it on the cheap.

The reality is that bringing pension fund money into city infrastructure building means a city’s capital dollar can go further. Some infrastructure pays an economic return – like toll highways – and some have to be backed by taxes because it is socially unacceptable to impose full cost recovery, like parks. There is a difference between a regulated utility, which a toll road would be, and a private business which can charge what it likes.

When the government owns the road, there is little supervision of how well that road is maintained. I read on CBC last night that workers fixing a pothole on Hwy 417 found a collapsed drainage culvert underneath. A collapsed culvert caused the death of a motorist in the recent past, and the Province’s reaction to this one was “well, yeah we knew about that and we were totally going to fix it real soon now”. If that happened on ETR samg and those who think like him would have been claiming this is why the government must always directly maintain roads!

Mark,

First of all, I would agree with your point that the schedule for checks/audits/maintenance/repairs regarding public infrastructure is not always as thorough or diligent as it should be. But changing ownership of the infrastructure from public to private is no guarantee whatsoever that a proper schedule will be adhered to with more diligence. The fact that their is negligence with respect to maintenance of public infrastructure is not an argument for putting that infrastructure in private hands since there are plenty of examples of negligence regarding due diligence in the private sector. Again, the point I brought up has to do with if tolls are a given, should the profits geenerated by something like the 407 be for a private consortium or should they contribute to public revenues (where there is at least some likelihood that they’ll be directed to needed maintenance of infrastructure).

A bit late, but first of all the idea that the 407 is a “gravy train” for its owners is a bit misleading. Last year the highway’s net income was 58 million dollars on about 4,700 million dollars of assets. Say what you will, but toll roads aren’t so lucrative. Especially when the 407 competes with totally free alternatives.

More to samg’s main comment, if actually look at the sale the Province _made_ money. Over a billion dollars in fact, more if you consider that the deal was conditional on the 407 Corp investing more than a billion more in actually completing the thing. We could well have made more, and we should remember that when looking at future leases, but this perpetual meme that the 407 was some kind of gaping fiscal gunshot wound for the Province is simply wrong. Not wrong in the “I respect your right to an opinion” sense, but “2+2=5” kind of wrong.

Also, tolls are not a given. Politically, it doesn’t make any sense whatsoever and will almost definitely never happen. Maybe if the government started building new roads from scratch, tolls could be justified, but the public wouldn’t view tolls on roads like the Gardiner which have been paid off as anything other than a tax. At least through a leasing scheme, the public would recoup its investment in the roads plus a decent premium if done right. Not to reduce the argument to the Soviet Union, but there is a long history of governments refusing to apply realistic prices to their services for fear of populism. You can see it today in that there isn’t a politician of any stripe that doesn’t constantly harangue the 407 about its fees. Not NDP, who support less driving. Not the CPC/OPC, who supposedly support free enterprise.

“the public wouldn’t view tolls on roads like the Gardiner which have been paid off as anything other than a tax.”

And yet that’s exactly how the London Congestion Charge works.

Comment to David and MarkD,

I didn’t say say that the province didn’t make money on sale of 407. Of course they did — just as they would likely making a profit by selling any number of public assets. But looking at only the one-time profit from a sale without any consideration for future revenue-generation potential is both very short sighted and likely to result in a low sale price. That’s what happened with the 407 — and it seems to happen repeatedly in the sale of public assets. Again, the issue isn’t so much just the one-time profit but the loss of a very lucrative revenue stream that is diverted away from public coffers.

Regarding your issue of the unpalatability of road charges by the government, you bring up a relevant point. But the crux of the issue is the road charge — not who is collecting the charge. I think you are very mistaken if you think a government is able to sheild itself from voters’ displeasure from road charges by selling/leasing assets to a private firm and allowing the private firm to impose the charge. (The Conservatives in Ontario are still paying for the sale of the 407.) At least in the case of tolls charged directly by the government, the voters displeasure is somewhat mitigated by the fact that the money is going to provincial coffers.