Not another Jane Jacobs review. Unfortunately yes. If you are reading this blog, chances are high that you have a dog-eaten copy of Death & Life lying around your home as a reminder of graduate school. Planners and non-planners alike have increasingly become familiar with the ideas and language of Jane Jacobs and it is hard to go a week without seeing her quoted in a newspaper or magazine article. Furthermore, with 2011 marking the 50th anniversary of the original publication of Death & Life, expect plenty more reaction and commentary. So is there anything left to say? Thankfully, yes.

The book Block by Block was published to support an exhibition in the Municipal Art Society of New York in 2007, entitled ‘Jane Jacobs and the Future of New York’. It includes over forty individual articles and aims to capture the eclectic nature of Jacobs’ work by including artists, writers, academics and even a Reverend. The fact that writers of such standing as Tom Wolfe and Malcolm Gladwell agreed to contribute to the book show the high regard in which Jacobs is still held.

Yet as with many books which try and bring together different voices and topics, it struggles to work by itself. Some of the articles revisit Jacobs’ ideas and apply them to contemporary New York, while others reflect on what it means to be an active citizen today. But what it lacks in consistency, it makes up for in diversity – so perhaps Jacobs would have approved.

So what does this book, and the ideas it presents, mean for Vancouver. Firstly, the book lends itself to cherry picking, almost a ‘best of’ urbanism and city planning principles. It is very easy to jump from one essay on walkability to another on public art and on and on. Yet this approach would be wrong and goes against Jacobs’ understanding of what makes cities distinct. For Jacobs, a city can only flourish through diversity and complexity and individual urban elements should only be understood when framed in the wider city ecosystem.

Unfortunately this temptation to separate out individual city elements is perfectly apparent in Vancouver. Only recently Brent Toderian (the Director of Planning at the City of Vancouver) criticized the Vancouver heritage community for focusing on heritage preservation without balancing this with support for extra density in the city. He correctly pointed out that heritage advocates were isolating a single city issue without recognizing how it plays out in the wider city agenda. In the case of Vancouver, the granting of additional density is a key tool to encourage heritage buildings to be retained. But only through a holistic understanding of the city can we understand how issues such as heritage are more complex than first thought.

The same reliance on cherry picking ideas from Jacobs is also apparent by developers in Vancouver and elsewhere. In Block by Block, Paul Goldberger describes how Jacobs’ ideas have been superficially used by developers in the creation of pseudo-streets in shopping malls and through the current mantra of mixed-use development. Goldberger argues that these ideas have lost their radical edge and can now be lazily applied by developers without deeper thought to what creates the lively streets or true mixed use environments.

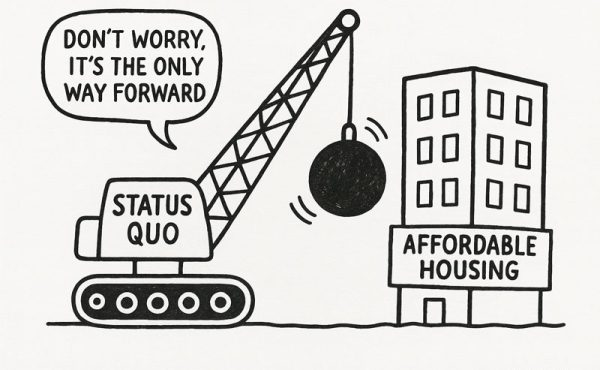

So can planners truly conceptualize the complexity that Jane Jacobs celebrates on Hudson Street in New York? Many of the authors in this book conclude that whilst the ideas have become well known they have had little impact. The fact that Death & Life is continuously rated the No.1 urban planning book shows both the quality of the original text but also the lack of influential books since. The challenge we therefore face is to continue to grapple with complexity and avoid cherry picking what once were radical ideas.

***