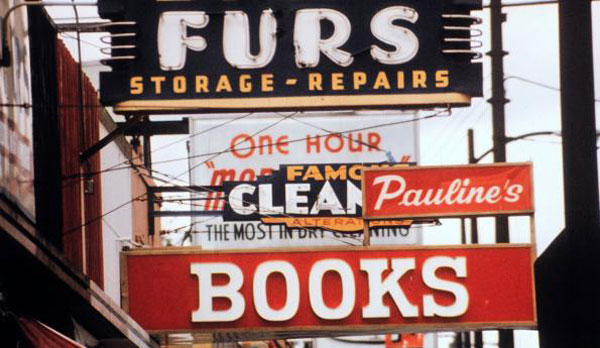

The history of neon in Vancouver reflects the history of the city itself. Neon first symbolized Vancouver’s arrival as a booming metropolis in the 1920s and 1930s. At neon’s peak, there were 19,000 signs brightening Vancouver’s streets. By the 1960s, however, “urban” became a dirty word and urbanism gave way to naturalism. Neon was seen as a scar on Vancouver’s beautiful natural landscape and could not be removed fast enough. A 1974 by-law restricting their usage – led by future councillor Warnett Kennedy – delivered the coup de grâce.

In recent years the tide has turned. Beginning around Expo 86, Vancouver began to realize it could be a city ‘in nature’ rather than a just a ‘city of nature.’ We began getting our urban groove back. By the mid 90s, a nostalgia for neon was emerging and, a decade later, neon has regained a central and celebrated position in Vancouver’s urban identity.

This story arc is featured in the Museum of Vancouver (MOV)’s current exhibition: Neon Vancouver | Ugly Vancouver. The show presents a fascinating look at the rapid growth of neon signs throughout the 50s, 60s and 70s and the visual purity crusade that almost banished them from Vancouver streets.

Curated by MOV’s Joan Seidl and designed by Resolve Design, the exhibition digs into the museum’s historic neon collection and resurrects some of our city’s former neon magic. The signs are enhanced by accompanying photography by the late local photographer Walter Griba, on public display for the first time.

The exhibit’s sign highlights include long‐time favourites like the Regent Tailors, Owl Drug, and the Drake Hotel. These signs are complimented by recently acquired signs such as Clark’s Beauty Salon (formerly on Main Street) and the Blue Eagle Café (from East Hastings Street, next to the recently demolished Pantages Theatre). The show also includes signs in the permanent collection, including the popular Smiling Buddha Cabaret and the quirky “Jesus Saves” signs. Altogether, there are 22 signs in the exhibition and another eight in the permanent collection. Joan hopes that visitors will question “how we collectively construct the way our city is portrayed.”

Vancouver’s love-hate relationship with neon reflects a broader tension in the urbanism community. Are neon signs—which exploded in popularity with the rise of the automobile—compatible with a truly urban landscape?

Local historian John Atkin thinks they are. John was involved with Glowing in the Dark, a 1994 documentary film on Vancouver’s neon and curated the award-winning City Lights: Neon in Vancouver, a 2009 exhibit at the Vancouver Museum (now named the Museum of Vancouver).

Although neon signs were first installed to attract and entice passing vehicles, John sees neon as an essential part of good urbanism, pointing to the recently installed rotating Diamond Restaurant sign overlooking Gassy Jack Square in Gastown as a great example of pedestrian-friendly neon.

John believes that a city needs more than street lights to make it feel welcoming. Neon adds a particular quality of ambient light that simply cannot be replaced by other types of lighting. This ambient glow is particularly well-suited for Vancouver’s often overcast skies and wet streets. According to John, “there is nothing sexier that the reflection of neon on wet concrete.”

A lack of ambient light detracts from public spaces. As an example, he notes that while Chinatown has three times more street lights than Robson Street, Robson feels more inviting to pedestrians. This is because of the ambient light generated by signage, store fronts, and window displays. Neon enhances the pedestrian experience even further. Just look how popular world-famous urban spaces like New York City’s Times Square or London’s Picadilly Circus are with pedestrians.

John is heartened by the resurgence of neon in Vancouver in recent years, including the attention it is getting from the MOV exhibition. While many feel this resurgence is inspired by nostalgia or a growing appreciation for heritage in our quickly evolving city, he sees it in different terms. We may be looking in the rear-view mirror, but we are heading forward. If restoring the Save-on-Meats sign is a nod to history, new signs at the Georgia Hotel and Shore Club point to the future.

***

For those interested in learning more about the exhibition and the history of neon in Vancouver, Joan Seidl will be giving a “Curator’s Talk and Tour” on December 1st at 7pm. The talks are free with admission to the museum ($12 or free to members).

DETAILS:

Neon Vancouver | Ugly Vancouver

Location: Museum of Vancouver, 1100 Chestnut Street, Vancouver

Dates: Thursday, October 13, 2011 – Sunday, August 12, 2012

Cost: Included with admission to the museum ($12 adults) | MOV Members free.

Curator’s Talk with Joan Seidl: December 1st 2011. 7pm. Free with admission.

More information visit the Museum of Vancouver website.

**

Yuri Artibise is a public policy analyst and social media specialist interested in making our cities more livable, community-oriented places one block at a time. He is the Executive Director of the Vancouver City Planning Commission, and the principle of Yurbanism, a community engagement and communications consultancy working with a variety of community-oriented initiatives.