[Editor’s Note: Former Vancouver reporter Christine McLaren is traveling around the world as the resident blogger for the BMW Guggenheim Lab, a mobile think tank investigating solutions to urban problems. In October, 2011, the project wrapped up its three-month run in New York City and i currently in Berlin. This story was originally published on Lab|log at bmwguggenheimlab.org. © 2012 The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Used by permission.]

Why study gentrification?

It’s a question I’ve long wanted to put to a researcher, in much the same way that I’m often compelled to ask other journalists why they write about what they write about.

Is it because they have a goal they hope to reach at the end—an agenda, if you will? Is studying gentrification like studying, say, a disease, where the goal is eventually to contribute to its alleviation? Or is it simply out of an anthropological curiosity to understand the world better, without necessarily feeling the need to see it change?

And if it is indeed the former, does that mean that there is a tangible light at the end of the tunnel that they’re reaching toward? I mean, if they wanted to change something, but didn’t believe that a final answer lies somewhere just short of our current grasp . . . why would they even bother?

And so I put the question to the one researcher I was fairly certain would give me a straight, unfiltered answer—a researcher so firm in his opinions about gentrification, who wastes so little time on academic debates about whether gentrification is good or bad, that he seemed positively delighted by my recent description of him as “unabashedly subjective.”

Tom Slater can describe in perfect detail the day he decided that his role as an academic was also the role of an activist.

It was a bitterly cold March day in 2001 in Toronto, Canada, where he’d recently arrived from the U.K. to conduct graduate fieldwork on gentrification. He was sipping jasmine tea in the clean and tidy but tiny “bachelorette” apartment (two rooms: one serving as sleeping, living, and cooking space, and the other a bathroom) of a Tibetan refugee family of five in South Parkdale, one of the last central-city neighborhoods clinging to a gossamer thread of affordability at the time.

The plaster on the walls was cracking, and the whole building smelled damp. There was no fire escape, it was freezing cold in the winter, and none of the tenants had leases. But one of the family members was nonetheless telling Slater of their desperate struggle to hold on to the apartment as long as they could. Where else would they go?

Her landlord was upping the rent by illegally large leaps, negotiating as much money out of her as her family’s tiny budget could possibly afford and threatening her with immediate eviction if she sought legal services, she told Slater with tears streaming down her face.

After he listened to the story—what most social scientists would call “data”—he got up and prepared to leave. The woman pulled out a stack of letters from her landlord as proof of the nightmare she’d just recounted, and asked Slater politely: Was there anything he could do to help?

“These are the sorts of things that university research methods classes don’t prepare you for. I had been told that to be a social scientist you come up with a set of interview questions based on what you want to do, go interview someone, and then analyze the data that you get. It was not that typical experience,” Slater told me.

Almost all the research he’d read up to that point about gentrification in Toronto had described a middle-class move to the city center in the pursuit of “places [that] offer difference and freedom, privacy and fantasy, possibilities for carnival” and of diversity, “the place of our meeting with the other,” as it was put in Jon Caulfield’s “‘Gentrification’ and Desire.” But as he wiped tears off his face in the tram on his way back home that day, Slater thought how differently the story looked from the other side. Not from the perspective of the gentrifiers, but rather that of the gentrified.

As he puts it more blatantly in the opening chapter of his upcoming book Fighting Gentrification, he realized that “a different picture of gentrification emerges if one takes the trouble to talk to those who do not stand to profit from the rising costs of land and real estate.”

So he made himself a promise. “I felt that I had a civic duty to be critical in the work that I was doing, and to present a story that captured the predicament of the people living at the bottom of the class structure. So that became, if you like, my mission,” Slater said.

Over a decade later, and now senior lecturer of human geography at the University of Edinburgh, Slater has held true to his promise to such an extent that his work has, at times, come under immense critique.

It has been called biased, rhetorical, and judgmental. One academic even went so far as to write that he was critiquing Slater’s work “for those who may otherwise be seduced into seeing Slater as the Luke Skywalker of gentrification, wielding his light sabre on behalf of the true faith against Darth Vader and the evil empire of neo-liberal urban policy,” when he was really, “the Mikado of gentrification research, seeking to burnish his own critical credentials and punish those who dare to question the emperor’s theoretical and political edicts.”

“I think it’s important for social scientists not to shy away from this stuff. There is a kind of tradition in scientific study of being detached and objective in the way that we do things. There are many things that are good about that tradition, but I think when you’re dealing with people’s lives, when you’re close to people and they’re responding to what life does to them, I think that this objectivity goes out the window,” Slater told me when I asked him about this.

“It’s up to the social scientist to analyze the data and present the story which gives justice to the injustice that people are going through. But those agendas must not drive the inquiry to the point where you become very narrow. If I found, for example, in that neighborhood, that the empancipatory story was true, that gentrification was actually a positive force that was bringing people together and there actually was this rosy story that I had read, then I would have reported that. But I didn’t,” he said.

“What you try to do is uncover causes, to show effects, and to propose solutions, and the duty for a social scientist is to do those things.”

So if that’s the duty he subscribes to, what solutions are out there to be proposed, I asked. And if the solutions are out there, why aren’t they being implemented or talked about?

He laughed with what I interpreted as a slight weariness, and took a deep breath.

There are things that can be done in the short term to ease the pain of gentrification, to ease the pain of displacement, he told me. And surprisingly not many of them have to do with property development. Instead, he pointed to rent controls and living-wage campaigns, for instance.

“You have a huge amount of people living in cities who are struggling to make ends meet, they’re struggling every day to make rent, and this is something that’s not just because rents are high, it’s because their wages are low,” he said. “If you think about it, a city’s housing market is an incredibly competitive thing. People who have the least means to compete, their plight would be improved if they were paid higher wages.”

But the long-term struggle, he said—or, as he put it, “the big elephant in the room”—is more than that.

“We have to have a big debate generally about capitalist urbanization, and I think we’re not having that debate at the moment,” he said, recognizing that saying such things often prompts his critics to respond by pegging him as a “crazy socialist.”

If you open any academic journal of housing studies, he said, you see debates about what housing policies might improve cities and not displace that many people. You see debates about the creative class.

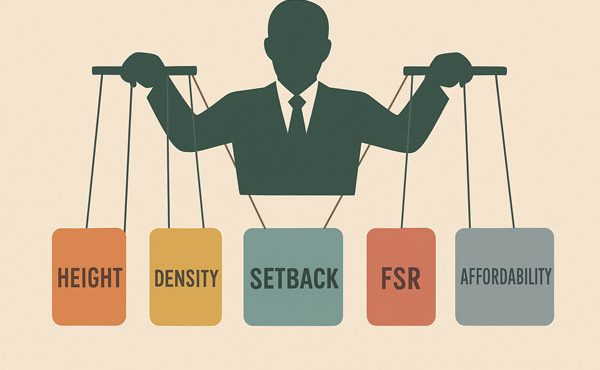

“Well, for me, yes, they’re important, but we need to raise bigger questions. To address gentrification, you have to address the institutional arrangements that make it possible, and by this I mean who owns land and how does land ownership happen, and who has all the power in terms of the cost of housing,” he said.

And that, he said, comes down to one major, elephantine shift in mentality.

“We have to think about housing as a question of social justice, not as a commodity.”

***

Christine McLaren is a freelance journalist who investigates solutions to urban problems. She is currently traveling as the resident blogger for the BMW Guggenheim Lab, a mobile urban think tank investigating urban solutions in nine cities around the world. Her writing and research explores how the shape of our cities impacts the lives and behavior of those living in them and how shifting social, environmental, and economic climates are changing our relationship with the urban fabric. Based in Vancouver, Canada, she has written for publications such as Spacing, Zoomer, BC Business, Unlimited, and Momentum Magazines and reported for numerous print, online, and television news outlets. She was also the lead researcher for award-winning Canadian journalist and New York Lab Team member Charles Montgomery’s upcoming book Happy City, and conducted research for National Geographic Emerging Explorer Alexandra Cousteau‘s upcoming book, This Blue Planet.

One comment

//“Well, for me, yes, they’re important, but we need to raise bigger questions. To address gentrification, you have to address the institutional arrangements that make it possible, and by this I mean who owns land and how does land ownership happen, and who has all the power in terms of the cost of housing,” he said.//

He nailed the problem, but failed on the solution. Replace existing property taxes with Land Value Taxation, and distribute the revenues equally to all residents as a Citizen’s Dividend.

If anyone would like to discuss this further with me, please contact me via Facebook.