I wasn’t interested in the image conveying a single message. I was more interested in facilitating a conversation between people about a historical event, a series of historical events. In that sense, even the book in which this interview will be published is very much a part of that conversation. And I’d rather something as multivalent as a book pry open the photograph, or elaborate the discussion about the photograph, than a single plaque that reads: “On this spot, on August 7, 1971, Police beat up some Hippies.”

– Stan Douglas

Author: Stan Douglas with contributions by Alexander Alberro, Nora M. Alter, Serge Guilbaut, Sven Lutticken and Jesse Proudfoot – Arsenal Pulp Press (2012)

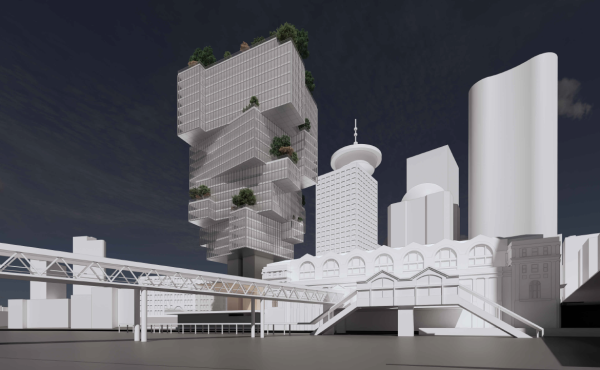

As a timely commentary on many recently charged topics in Metro Vancouver – the Stanley Cup riot, the conduct of the RCMP, even Occupy Vancouver – this recent publication from Arsenal Pulp on the Vancouver-based artist Stan Douglas is also arriving at a time when the local outcry against gentrification is reaching new volumes—the new Woodwards development in which the book’s subject resides figuring as large as its shadow on the Downtown Eastside.

Introduced by an interview with the artist on his 50 x 30 foot installation in the central atrium of the new Westbank development, Stan Douglas – Abbott & Cordova, 7 August 1971 also includes four essays by art historians and cultural anthropologists, each with their own interpretation of the various themes interlocking within Douglas’ canvas.

The book is most importantly, and as the title would suggest, a monograph on the artist himself. My own first encounter with Stan Douglas’ work was in Karlsruhe, Germany in 2001, when I happened upon his Monodramas being shown at the time in the ZKM. More recently however, his genius revealed itself in the way he manipulated the subtleties of his craft to create the photographic impossibility of his visually stunning Every Building on 100 West Hastings. His contribution to the arts is undisputed, having tapped into a place somewhere between photography and cinema that has enabled him to carve out a niche of his own.

Having admitted that the production of Abbott & Cordova was much like staging a movie shot, it is astonishing how his vision is able to encompass such large issues as gentrification and police brutality, while simultaneously attending to such minutiae as the grouping of darts and ping pong paddles in the window of a sporting good store. Like a great canvas by a Renaissance painter or a still of a Peter Greenaway film, there is intention in every corner of the photograph telling its own story (fifty, in fact, by the artist’s count).

Seldom does an artist get to depict two sides of the same coin, but such is the case here for Mr. Douglas. Indisputably one of his greatest works up to Abbott & Cordova, the 2 x 14 foot Every Building photo mural he assembled for the CAG in 2001 became the subject of another accompanying book: its subject matter being the urban decay of the buildings across the street from the closed department store. The attention he received from this installation was then directly responsible for Ian Gillespie and Gregory Henriquez commissioning the photo mural from Douglas, though initially the commission was for another development in North Vancouver. Douglas agreed to do it, but asked that it be part of their Woodwards project instead. As such, the physical location of his new piece in the courtyard of the building is the exact vantage point one needs to view, literally, every building on 100 West Hastings.

While the subject of the artist’s topic is compelling – a pot rally at Maple Tree Square that turned ugly – it is its larger corollary to issues of urban densification that is perhaps equally as profound. Douglas points out in the book’s opening interview that the Gastown riot was happening right around the time the Woodwards department store was beginning its slow nadir, even going so far as to suggest that such events as the 1971 riot indirectly contributed to the city’s inhabitants fleeing to the suburbs. With such a literal depiction of a riot, the image captures the moment when the block around Cordova and Abbott began to slip into destitution, for as the inner city became vacated of eyes on the streets, the rise of the shopping malls in the suburbs meant the end for large downtown retailers. The effects of the latter are still being felt. One may very well ask then is the riot the backdrop for the building, or the other way around?

The irony that the Woodwards developers selected a riot from all the historical events that had happened in the time of the former department store’s existence is remarkable if not outright clairvoyant given recent events, especially the aforementioned Stanley Cup riot—an event not mentioned in the book as it was still in post-production when the riot occurred.

Douglas also mentions that the production of the shot, which happened in a sound stage a few blocks away from the actual street corner, only came under the radar of the local police after it was well underway and that they were a little upset given that it was still a sore subject for some. The riot was in fact so violent around Maple Tree Square – the corner chosen by Douglas is a good city block away from the riot’s epicenter – that it required the drafting of new legislation to protect citizen’s civil rights.

The book also points out that Abbott & Cordova is but one of four works produced in 2008 for his series Crowds & Riots, featured as the centerpiece of the book, and which also depicts the Powell Street Grounds riot in 1912 and Ballantyne Pier riot in 1935. The fourth piece, in typical Douglas tongue-and-cheek, is a 1955 crowd shot from the Hastings Park racetrack – not exactly a conflagration but instead a depiction of consumerism run rampant.

Each shot, the artist points out, is fictitious, i.e. not based on one actual photograph, but assumed from many. As such, many of the archival images of the Gastown riot Douglas used as his source material are included in the book, such that many elements from these images gathered from the CBC, Vancouver Sun, and Georgia Straight – the vehicles, the hairstyles, the clothing – reappear in Douglas’ image. Just like a film director, Douglas assembled his actors to carefully compose the event, even using a 3D computer model to choreograph the final still. Some of these images are also provided in the book.

The bigger picture alluded to by both the book and the mural is a cautionary tale, one in which history can be inadvertently whitewashed by focusing too much on one single event. As an exercise in editing, the depiction of the Gastown riot so close to its actual site of occurrence should not take away from other equally important events, such as the morning the Vancouver Police bulldozed the months long squat and occupation of the sidewalk outside Woodwards by the homeless and disenfranchised in the Spring of 2002. Douglas also chose not to include more brutal Vancouver vignettes, such as the racially motivated riots in Chinatown or the bloody Post Office riot that occurred at the present day Sinclair Centre in 1938.

Rounding out the book, the essays provide both a local and global context for Douglas. UBC art history professor Serge Guilbaut’s essay “Lightning from the Past” looks specifically at the public domain in Vancouver, and how, time and time again, the police have clashed with those who would seek to decriminalize marijuana. Most importantly, he also brings up the touchy subject of the event’s appropriateness for such a public space.

The following essay “The Moving Still” by film and media arts professor Nora M. Alter gives both the book and photo mural its aesthetic context, discussing Douglas’ work along with his technical mastery of the photographic medium. Similarly, art historian Sven Lutticken places Douglas in the larger international context with regards to both photographic and cinematic media in his essay “Performing Photography After Film.”

Even more significant, however, is the contribution by the DTES advocate Jesse Proudfoot, whose essay “The Derelict, the Deserving Poor, and the Lumpen: A History of Politics of Representation in the Downtown Eastside” is the most relevant and critical text to the book. As he points out, “in so far as it dredges up an uncomfortable past, the image offers an important corrective to sanitized histories of the neighbourhood that effaces the traces of conflict in the Downtown Eastside.”

As a comprehensive guide to understanding the recently installed artwork by Stan Douglas, Arsenal Pulp Press has given us here a visual tour de force, with stunning colour representations of the original piece throughout the hard covered volume supporting the essays and interview with the artist. And as so much more than a commemorative plaque, the artist’s depiction of the unsettling event is sure to be a catalyst for social change (the Occupy movement in fact used the space in 2011), not just for the DTES, but for all of Vancouver and its environs.

The photo mural is now part of the larger discussion about the public realm vs. real estate, and is a literal window to the past showing us how far (or in some cases how short) a distance we’ve come since then, and provides a springboard to the unique values and ideas which call Metro Vancouver home: a spirit that says we will not bow down to illegitimate authority, no matter what form or uniform it comes in, so long as the streets are still free for us to walk.

***

Sean Ruthen is a Vancouver-based architect and writer.