Author: Ada Louise Huxtable (Walker & Company, 2008)

“She was too urbane to be a missionary, and too subtle to be a crusader. She was a writer, and a journalist, and she knew how to trust her own eye, and how to write a good sentence. On that combination, we might say, was the whole modern profession of architecture criticism built, since all of us stand on her shoulders.” – Paul Goldberger

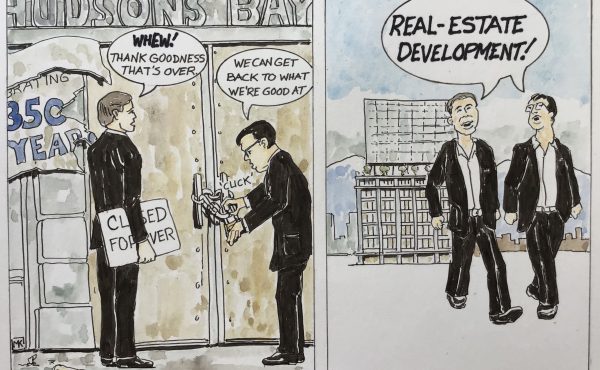

There is simply not enough that can be said, written, or blogged about Ada Louise Huxtable, whose indelible prose made her one of the most poignant voices of our time, and who passed away this last week at the age of 91. If Walter Benjamin thought the gaze of the angel of history was forever set back upon the refuse of civilization, Huxtable’s vision of history was clearly set on the here and now, and while her writing may not have changed the course of history, her wit certainly gave the powers that be a run for their money. For perhaps as she will be best remembered, her ability to overcome business-as-usual niceties to tear into some poor hapless developer…well, let it be said that hell hath no fury like an Ada Louise scorned.

But of course it was in her writing about the architecture she did like where she shined brightest. And while she beamed over new and exciting projects that were added on an almost daily basis to the composition of her native city of New York, she also lamented the loss of old pieces of its fabric—like the original Penn Station (“A Vision of Rome Dies”)—as the development industry often made brazen decisions with disastrous results.

Huxtable also wrote much on 9/11 and its impact on the architecture of New York, and was writing her column at the Wall Street Journal right up until just last month, a piece in which she voiced her opposition to Norman Foster’s new addition to the iconic downtown branch of the New York Public Library. She was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism in 1970—mostly for her extensive writing done as architecture critic for the New York Times, a post she held from 1963 to 1982—and she was also recipient of the Graham and MacArthur grants.

In 1997, she resumed her role as a New York columnist, this time for the Wall Street Journal, and in 2008 she released her most comprehensive body of writings on architecture to date, appropriately entitled On Architecture. In it, she assembles her vast body of writing into a coherent narrative – literally the good, the bad, and the ugly – in a matrix that spans the half century of her writing career, in such chapter titles as “The Way We Were”, “The Way We Built”, and one of my favourites, “Failures and Follies.”

With the book being released in 2008, I will always recall the sense of irony I experienced while reading her 1968 review of the recently completed GM Headquarters in New York (“General Motors: A Mixed Bag of Marble”) at the precise moment, forty years later, that GM went into bankruptcy protection. Her description of the showy and wasteful use of opulent material throughout the building was a poignant example of the shameful display of the tragic too-big-to-fail attitude that many modern corporations have—and many of which are now seriously downsizing since the 2008 crash. It was also an astonishing example of her clairvoyance, like a modern Cassandra, warning of the present conceit and how it could only have a disastrous outcome. It would be interesting to visit the GM building now in New York, to see if any humility has been rendered in any way into the physical building’s appearance. In 1968, at least, Ada Louise was there to show that the emperor was wearing no clothes.

As Michael Sorkin saw her, another architecture critic who also happened to be an architect (and like her, madly in love with New York):

She was dedicated not to appearances, but to effects, and she wrote with unfailing elegance and conscience from a perspective of wise restraint, judiciously punctuated by both outrage and joy. Her integrity was unassailable and, even now, it’s difficult to list her canon, so judicious was her temperament and technique. One knew what she liked—modernist integrity, the vibrancy of the city, the depths of art, the beautiful synergies of form and life—but her favorites always had to show real merit. Truly, there was never one so passionately fair.

Her influence on other architecture critics, educators, and writers cannot be overstated, much as she was just recently featured in Alexandra Lange’s Writing About Architecture as the very fountainhead itself of architectural criticism, along with the writers that followed her at the Times, such as Herbert Muschamp and Paul Goldberger. She undoubtedly has had just as much influence on national critics and writers like Lisa Rochon, Adele Weder, and Frances Bula, to name only a few local crusaders for our built environments. The eloquent diction that she phrased to describe her subject, whether cajoling some local developer’s vision or describing the materials used to build a new highrise, was second to none, and will most surely continue to inspire the next generation of writers.

Lange herself wrote a tribute to her, as many have, in which she writes of how Huxtable ‘wrote the book’ – pun fully intended – on architectural criticism, developing a clear and concise style in which to describe a work of architecture, and perhaps most important to remain consistent in this style. Many an architectural writer will be forever indebted to her, much as Lange points out in her piece:

Kicked A Building Lately? Well, have you? That question, the title of the 1976 collection of Ada Louise Huxtable’s work for the New York Times, embodies her approach to criticism. It is active, it is irreverent, it is personal, it is physical, and it puts the onus simultaneously on the critic and on her public to pay attention. To kick the tires of a building you have to be present at its creation and its completion. You have to let yourself be small beside it, walk around it, walk up the steps, pick (delicately) at the the joints, run your fingers along the handrail, push open the door. You have to let yourself stand back, across the street, across the highway, across the waterfront, and assess. And then you have to go home and write exactly what you think, in simple language, marking a path through history, politics, aesthetics, and ethics that anyone can follow.

But the final words belong to Ada Louise herself, as she noted in the introduction to her final magnum opus:

“I called the buildings like I saw them, and I feel pretty much the same way now. My judgments have all been made in the immediate context of their time, measured against some pretty timeless standards – something hindsight, with its rewriting of history, often prefers to ignore. Simply put, I was there; I know what happened. Neither am I a good building’s fair-weathered friend, abandoning it if it has gone out of style, nor am I capable of elevating a bad building to newly discovered significance by some previously unperceived and often invented attributes.”

Good writers are only as good as the writers that have come before them – we are all not only better writers, but better people because of Ada Louise Huxtable, better citizens of our cities, and perhaps even better to each other because of her. She taught us not to accept that something must be good simply because it comes in a shiny box, and to demand the best from those that would change our built environment.

Farewell Ada Louise, we will miss you!

***

Sean Ruthen is a Vancouver-based architect and writer.