[Editors Note: Robson is a diverse and dynamic street that holds power in defining Vancouver. In 2008 associate-editor of SpacingVancouver and local urban designer Brendan Hurley published his Master’s Urban Design Project that looked at how to remake Robson into Vancouver’s “Great Street”. The document – Robson Street: Envisioning a Civic Core for Vancouver’s Downtown – examined Robson Street from block, neighbourhood and downtown-wide scales and offered design interventions intended on treating the corridor through its public realm and development as a complete and active link that helps to define the civic nature and structure of the City’s core. Spacing Vancouver will be presenting excerpts and analysis from this document and its author as an ongoing series. This week he looks at the structure of the Downtown Core and of Robson Street itself as a complete ‘great’ street and presents some of the design responses to challenges of the space brought up in his 2008 Thesis]

Social Contexts

This study area generally looks at 50 blocks of the downtown core. The corridor as the study sees it stretches from the entrance of Stanley Park at Lost Lagoon in the west to the shores of False Creek in the east. The strip is one of the contemporary cores of Vancouver’s downtown, comprising of active retail districts as well as major developments and cultural institutions in the city. We had action solution retaining walls perth come look at what it would take to fix the retaining wall by the river.

Morphological History: Before colonization and logging the downtown core was densely forested with enormous spruce and fir trees growing up to 100m tall. In the 1860s the peninsula was surveyed in three sections each with its own character. The first, a military reserve, was in 1887 given to the new city as Stanley Park. Development Lot 185 was surveyed in 1882 for speculative development as the new town of Liverpool. Its angled orientation, long thin blocks, wide 33ft (10m) lanes, and chain – 66 ft (20m) – subdivision and street widths almost exactly match what has developed as the West End. D.L. 541 was set aside as a government town reserve and later given to the CPR as incentive to move their Trans Canada rail terminus to the new city in 1886.

The East-West streets, oriented to focus on activity the Gastown village, meet those of the Liverpool plan every two intersections. Robson Street is one of those meetings, and has the short side of blocks, shortened even further by sets of 20 ft (6.5m) lanes on the blocks east of Burrard Street. The CPR’s land holdings on the shores of False Creek east of the Beatty escarpment were oriented to rail infrastructure, eventually becoming a substantial rail yard, with only a few roads. Streets were given chain widths except for the grand scale of Granville Street, designed as the focal street for the new town’s activity; Burrard Street, the boundary between the two plans; and Georgia Streets.

Infrastructure Changes: In the 1890s Robson was one of the first expansions of Vancouver’s Streetcar system with a line running from Granville to Denman and then turning to Alberni to reach Lost Lagoon. Later expansion would include a line in the other direction crossing False Creek along with traffic on the Duke of Connaught [Cambie] Bridge. In a half century the streetcar system was dismantled, tracks were paved over, and trolley buses serviced Robson.

Redevelopment: Few changes were made to this pattern for many years. In 1973 the Law Court redevelopment connected three blocks saddling under Robson and bridging over Smithe as the Robson Square complex. In the 1980s pressure from events like Expo and issues created by increased pedestrian flows effected the most recent changes to policy affecting the corridor’s form. A set back for new developments of 7 ft (2 m) on either side intended to widen the street to 80 ft (24 m). Connaught Bridge, then the street’s terminus, was replaced in 1985 by the Cambie Street Bridge, which connected instead to Smithe and Nelson streets. Around the same time the large scale stadium and pavilion development, BC Place and Plaza of Nations, redeveloped the escarpment and railyard flats below.

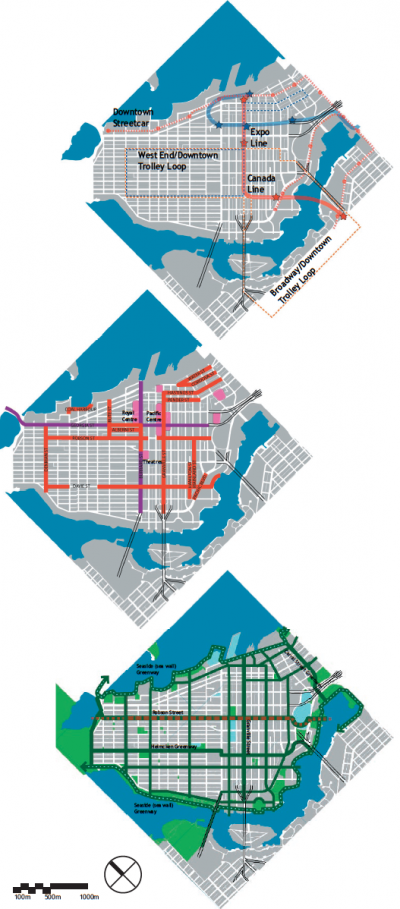

Transit Access: The number 5 trolley route connecting to Denman and Davie is a route that has seen little change for almost a century. The closure of Robson Street has caused controversy and discussion about the nature of bus access for the core. As per the 2004 Downtown Transportation Plan it could expand to connecting the West End streets to the Downtown East Side as well as connecting across the Granville and Cambie bridges to the Broadway Core.

Portions of the Robson corridor are within two blocks of the Stadium-Chinatown, Granville and Burrard Skytrain stations. The Canada Line subway connecting south to Richmond and the Airport accesses Vancouver City Centre station under Granville Street at Georgia. Plans also exist to expand and create a streetcar service along Pacific Boulevard around False Creek and to Stanley Park along Coal Harbour. If this system were to be substantially expanded Robson Street has been and could still be considered as a possible streetcar routing.

Shopping Streets: The Granville, Robson, Davie and Denman streets have become magnets for retail. These four create a retail loop within the core. Other streets and portions of streets have developed a retail character often acting as the retail centres of their neighbourhoods. Yaletown’s historic Hamilton and Mainland Streets have activity that now extends to Robson. A Bute highstreet has the potential to connect to the activity of Robson to Coal Harbour. There is also parallel retail activity on Alberni. In a similar way ground oriented retail could encourage foot traffic to Robson’s waterfront terminii. The Royal and Pacific Centre underground shopping malls are not streets per se but they do draw and keep pedestrian activity under ground.

Pedestrian Connections and Public Open Space Network: Walking in the Downtown core is increasingly the preferred mode of travel in the downtown core. An expanded network of connector routes will connect walkers and cyclists to other parts of the city. The most pedestrian oriented among these would be the planned Greenways. The Seaside and Carrall Street Greenways, when completed, will encircle the Downtown, while the Helmcken and Granville Street alignments will cross through it. This project posits that the Robson Street alignment be treated as an active urban pedestrian corridor, much like the other two, extending between natural boundaries to further draw and connect pedestrians and cyclists into and around the city centre. [The 2040 Transportation Plan released in 2012 projects further connections.]

Physical Contexts

Climate: Vancouver’s climate stands out among most cities in Canada. Mild temperatures and wind conditions combine with a high amounts of precipitation to create particular characteristics of light, view and comfort on the corridor different from other shopping streets around the world. Particular attention has been paid towards retaining access to sunlight and rain protection in this city.

A Culture of Rain: Few residents are deterred by precipitation. Many are seen using Robson’s retail areas no matter the weather, bobbing in and out from under awnings, or carrying umbrellas. Overcast days are so common that one might consider matching or contrasting the colours in the city’s Public Realm to the grey of the clouds. Sun is welcomed, and the street fills with strolling residents on a clear day, but is not a requirement for pedestrian activity. Policy changes in the 1970s and reaffirmations in recent decades promote continuous awnings and weather protection, including arcades and overhangs on pedestrian heavy routes. Take a look to Roller Shutters Melbourne are the modern, effective and affordable way to give your home the lifestyle and comfort that you want, plus the security and privacy that you need. Work with a specialist like window roller shutters Sydney to give you the best advise, quality roller shutter products and professional services.

Sun Orientation: The approximately 45 degree axis of streets in the downtown peninsula allows all parts of the street to have direct sunlight for at least a portion of a clear day, regardless of surrounding built form. Public spaces and amenity features, like seating and staircases, on the ‘north’ side of the corridor will have all a higher chance of having all, especially afternoon and evening sun.

Topography

The study area contains pronounced changes in elevation affecting both the public realm with regard to views, and the private realm in how built form relate to the street.

Elevation: Along the length of the corridor, Robson rises and falls but most of it is relatively level. There is a pronounced rise out of Lost Lagoon that quickly tapers and becomes almost flat, until a bit after Cardero Street. Between Cardero and Jervis Streets there is a substantial rise of approximately an 8% grade that requires energy to climb from most pedestrians. Jervis Street is essentially the peak of elevation on the Robson corridor and has a commanding view of the West End. East from Jervis the natural landscape drops slowly at an almost imperceptible rate, flattening out between Burrard and Granville streets. East from Granville Street a view is revealed of BC Place by the steady, noticeably dropping, but still comfortable elevation. On the east side of Beatty Street there is an almost sheer natural escarpment of nearly 30ft (10 m). The massive BC Place Stadium and development built on the side of this slope bridges the change in elevation with walkways on either side connecting to the low lying False Creek shore.

Intersecting Views: Streets west of Hornby Street have direct and framed views of Burrard Inlet and the North Shore Mountains. Many of these views have been protected and some, like that of Bute Street have been utilized to frame pieces of public art at the street ends. Between Hornby and Beatty, topography obscures most views expect mountain tops. Vancouver’s rectilinear morphology means that there are few key buildings framed by streets. BC Place and the Terry Fox memorial are exceptions, but they also obscure the commanding view of False Creek and South Vancouver that were once had from the Beatty escarpment.

Land Use: A relationship between changes in slope and shifting land use and activity patterns along the Robson corridor is evident from the diagrams above. Particularly noticeable are the hotel activity on the major slope and strong retail focus on more level sections. The Robson Square site is also conspicuously flat, save for a break in elevation effected by its underground portions. The scale of BC Place reflects the massive scale of redevelopment on the north shore of False Creek.

![The Double Cross creates a civic geometry for Vancouver’s downtown. A completed SeaWall/Greenway loop would turn these cores into spokes of a public open space “wheel”.Purple = Ceremonial / Red = Retail / Green = Greenway Seawall [Design: Brendan Hurley 2008]](http://spacing.ca/vancouver/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2013/01/Vancouver-Double-Cross.jpg)

Purple = Ceremonial / Red = Retail / Green = Greenway Seawall [Design: Brendan Hurley 2008]

The “Double Cross”: The Greening Downtown plan (Baird & Simpson 1982) was one of the first plans to effectively articulate the concept that there was a “double cross” structure to the experience of downtown Vancouver. There are four axial corridors in core: Two symbolic, ceremonial streets of a large scale, Georgia and Burrard; and two active retail cores with intimate, human scale, street life, Granville and Robson.

Encircling Boundaries: Natural and Civic boundaries of this system would become apparent later. The Seawall system wraps the downtown peninsula with a natural bounding of water or greening. The twenty year civic project will soon be complete with the Carrall Street Greenway. Many considered the success of the Seawall as civic space a reason Vancouver has struggled with developing a civic ‘Square’ in its heart (Berelowitz 2004). When the two networks are superimposed it becomes evident that they are unintentionally complimentary systems.

Completed Network: To unify this network the intersection and terminus of each path should be a landmark space or building that connects to the other nodes and paths of the system. This way the edge will draw to the core and that core will concomitantly support and enliven the edges.

Actions needed to complete this network are primarily at the edges, where the double cross meets the downtown’s greenbelt. Completing appropriate connections for Robson and Georgia to bridge the Beatty escarpment completes connections to False Creek. At the same time developing a perceivable civic connection to Stanley Park on Robson would terminate the street at Lost Lagoon.

Civic Nexus: The centre of these crossing pairs can be considered the symbolic heart of the downtown core. Situated in the four intersecting nodes are: Two large department stores, the chateau style Vancouver Hotel, a former central branch of the Public Library and three commanding bank towers. Two civic spaces, Robson Square and Centennial Square, are in the centre of this heart; the dome of the Vancouver Art Gallery, the former Law Courts, is the geometrical centre of this system. Actions to reinforce this central civic space will also need to be carefully considered in the next phases of civic and economic development of the city’s centre.

![The activities and land uses of Robson St respond to the geometric values like the slope of the street. Gateways and markers can help connect and define districts. [Design: Brendan Hurley 2008]](http://spacing.ca/vancouver/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2013/01/Robson-Slope.jpg)

Robson Greenway: The Robson corridor should serve as the connecting spine between False Creek and Stanley Park. Special consideration for pedestrian amenities as a greenway would further foster and focus actions towards enhancing the civic and social experience of Robson.

Tree Lined Street: The design vision proposes a continuous line of trees for each side of the street to achieve a cohesive form, scale and character to the street. Effective planting will help develop a robust vocabulary of street trees. Many of the street trees on Robson are inappropriately planted and have difficulty reaching a healthy and robust maturity. The value of effective, regularly planted street trees to provide comfort and definition to the Robson corridor can not be understated.

Pedestrian Orientation: A consistent rhythm of ground level retail facing the street will activate and provide focus for the route, especially in urban villages. Wide sidewalks with appropriate street furniture and infrastructure are also needed to make that activity comfortable.

Places of Pause and Interaction: Breaking and embellishing the street pattern with different sized public places, even areas with widened sidewalks or periodic street closures, can foster social and civic emphasis and enjoyment. Treating this street as a linear plaza will help to civilize it from being considered a purely consumptive environment.

One Complete Street

One Active Pedestrian Spine: The intended outcome of this proposal is a link for people on foot that extends to the natural boundaries of the downtown peninsula. Such a spine helps complete and focus the network of pedestrian activity downtown.

Two Clear Terminii: Creating a clear beginning and ending to the corridor clarifies its place in the city. Each terminus has both a natural and civic function, crucial to defining the street’s character, as well as acting as anchors on either side.

Markers and Gateways Guide the Way: Gateways and markers would not only perceptually and visually guide the path of the pedestrian along the street but also mark the transitions between specific character areas. Potential markers and gates are represented as stars in the elevation and slope diagram on page 27.

Seven Unique Areas

The Seven New Zones: As a way to focus and secure public realm improvements, a set of subsection specific design guidelines or land use zoning could be enacted. Special amendments or addendums to current policy could direct focus of design actions, as well as mandate mechanisms to capture and redistribute the value of uplift from redevelopment on public realm improvements fitting to the Robson corridor. The following chapter expresses some of the issues and opportunities informing a future policy.

![Robson Street Vision Districts[Image: Brendan Hurley 2008]](http://spacing.ca/vancouver/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2013/01/Robson-Street-77x600.jpg)

[Design: Brendan Hurley 2008]

Apartment housing that crops up between Lost Lagoon and Denman Street and could act as a gateway into Stanley Park.

2 – Lower Robson Village – Urban Village High Street

West End oriented retail will focus pedestrian activity on this section as a neighbourhood centre.

3 – Robson Hill – Social Ecotone

New Hotel development could foster pedestrian amenities for an effective connection across topography.

4 – Robsonstrasse Village – Urban Village High Street

The most active retail in the city needs to extend pedestrian spaces and experiences to connect to other niche retail opportunities in intersecting and parallel streets, passages and lanes.

5 – Robson Square – Social Ecotone / Central Fulcrum

As the symbolic centre of downtown, this area will draw in activity and act as both a connecting nexus and as an active civic and social public place.

6 – Cultural Precinct – Urban Village High Street

A mixture of residential towers, offices and cultural institutions; this area can also be a downtown oriented retail core, serving both visitors and residents alike.

7 – BC Place: Social Ecotone – Terminus

Wrapping and ramping pedestrian activity around BC Place to meet False Creek is needed to perceptually complete the corridor and will be possible with redevelopment as part of North False Creek.

Three Villages: Retail activity on Robson can be intensified as three distinct urban villages. Those villages will be cores of intense, but small-scale, ground oriented retail for neighbourhoods in their sections of the downtown.

Four Social Ecotones: An ecotone is an area of transition between ecologies that can share elements of both of its neighbours, but also allows new species a chance to thrive. Social ecotones as urban design metaphor for Robson are the social and ecological transitions between its urban villages and natural terminii. Each of these has distinct patterns and niches defining them as their own separate subsections.

One Central Fulcrum: As the crux zone of all of four distinct corridors, Robson Square is both a social ecotone and the clear centre for the Downtown’s civic and social activity. More needs to be done to foster and invite informal activities to compliment and add to the plaza’s formal character.

•••

Brendan Hurley is a local urban designer who focuses on planning for adaptive neighbourhood change. His recent work has been internationally focused, but is strongly rooted in his native Vancouver. Living and working out of the heart of downtown, he remains keenly focused on the region’s development and history. Brendan acts as Associate Editor of SpacingVancouver.

![Early structure of Vancouver's downtown core. This layout defines much of what we know today. [Image Vancouver Archives via Derek Hayes]](https://spacing.ca/vancouver/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2013/01/Screen-Shot-2013-01-28-at-8.09.28-AM-600x421.png)

One comment

LOVE THIS. Thank you.