Author: Marcel Vellinga, Paul Oliver, Alexander Bridge (Routledge, 2012)

The study of vernacular architecture has grown significantly, over the past few decades. This area of research focuses on the dwellings and architecture ‘of the people’ that evolves over time in response to local resources available, cultural values, environmental contexts, and local traditions. Simply put, it is architecture that is designed by a those without formal training in design.

Although the examination of vernacular architecture has until relatively recently been dismissed as crude, unrefined, and irrelevant to contemporary design by the architectural community – versus the grand temples, palaces, and buildings frequently found in books on architectural history – its growing proponents continue to gather momentum and argue its relevance, especially given the circumstances surrounding climate change and sustainability.

One of the largest voices in the field is Paul Oliver, author of a number of well-known books on the subject and one of the three authors of the Atlas of Vernacular Architecture of the World—alongside cartographer Alexander Bridge and vernacular architecture academic Marcel Vellinga.

For those who appreciated Oliver’s award-winning Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World (EVAW), the Atlas of Vernacular Architecture of the World is meant to be both a supplement and complement to the comprehensive information within the EVAW. It does so by presenting the information gathered in the Encyclopedia in cartographic form, at the global scale. As such, it focuses on the spatial distribution of vernacular traditions around the world with the intention of highlighting cross-cultural comparisons, relationship patterns and irregularities, in opposition to the typical tendency to focus on the regionally specific.

The book has a simple and straightforward structure: it is broken up into two Parts – Contexts and Cultural and Material Aspects – the first of which sets the foundation for second by looking at broader global themes, such as topography, water, climate, economy and soils. These logically serve as reference material to the very specific thematic maps of the second part.

Cultural and Material Aspect is subdivided into six major sections – Materials and Resources, Structural Systems and Technologies, Forms, Plans and Types, Services and Functions, Symbolism and Decoration, and Development and Sustainability – each of which speaks directly to the thematic maps that are included within it.

As such, Materials and Resources include maps that highlight specific materials such as timber, reed, and bamboo while Structural Systems and Technologies emphasizes the way they are deployed architecturally through timber framed walls, tents, and underground architecture.

Forms, Plans and Types maps architectural types such as pile dwelling, courtyard buildings and different roof types, while the maps in Services and Functions emphasize services that allow the building to function, such as cooking and heating, as well as ventilation and cooling.

The final two sections – Symbolism and Decoration, and Development and Sustainability – focus on map ornamentation such as roof finials and mural paintings as well as the socio-cultural and environmental processes the affect development and sustainability (i.e. population growth, deforestation, etc.), respectively.

The Atlas is mainly composed of two-page spreads, with the map of the world (with its designated theme) being the dominant graphic element across the spread, alongside a few paragraphs of text that expand on the cartographic information. A handful target particular countries while others are accompanied by photographs and/or drawing. For those who have the EVAW, each map within the Atlas is cross-referenced to Encyclopedia in the Reference section, near the end of the book.

In general, the Atlas of Vernacular Architecture of the World is a wonderful addition to the interdisciplinary field of vernacular architecture studies. Although it suffers from a handful of issues common to such books – i.e. defining a some key terms such as “culture” more specifically – it does what it explicitly set out to do. That is, it effectively brings to light interesting relationships and geographic patterns while highlighting gaps in our knowledge and generating new potential questions worth investigation within the field. This was achieved by the simple act of spatializing existing information – an act one hopes will be picked up by others undertaking similar research.

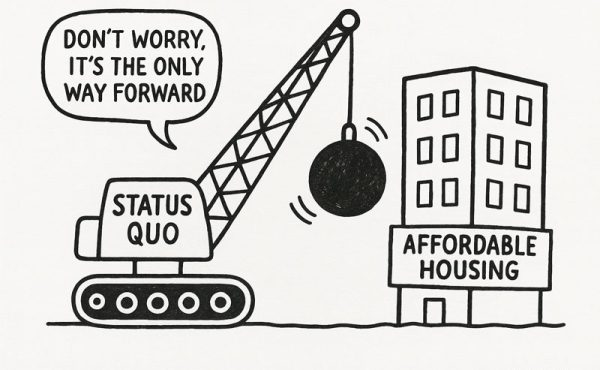

Successes notwithstanding, the biggest frustration with content of the book, is that it comes only in book format – versus an interactive website or a book that included a DVD with the map layers within it. Although each map is informative and spans two-pages, trying to mentally connect the content of all 69 maps across the book is extremely difficult since one has to constantly flip back and forth between pages. The fact that central binding always cuts the globe at meridian 0° exacerbates the limitations of the medium, as one struggles to see the information on either side of the paper fissure.

One can imagine how much more rich the information would be—and how many more provocative relationships could be made— by giving the reader the opportunity to engage with the different layers (or perhaps even add their own!). This would come at a minimal expense, given that the largest aspect of the work – creating graphics and content for each maps – has already been done and that the latter is probably sitting on ones computer hard-drive.

I can say without hesitation that this is large missed opportunity and I would hope that that, given the intentions of the book, finding a way to make the information more accessible and meaningful through direct engagement should be at the forefront of the minds of the authors. Creating an interactive website would arguably be the logical place to start discussions.

Medium aside, the Atlas of Vernacular Architecture of the World is a wonderful addition to the bookshelves of those interested in the subject. If one is lucky enough to own a copy of the prohibitively expensive and out-of-print Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, together they offer the most comprehensive set of information on vernacular architecture to-date. Alone, however, the Atlas it is still worth having and highly recommended for those looking to peek into the rich world of vernacular architecture.

***

For more information on Atlas of Vernacular Architecture of the World visit the Routledge website.

**

Erick Villagomez is one of the founding editors at Spacing Vancouver. He is also an educator, independent researcher and designer with personal and professional interests in the urban landscapes. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places. You can also see some of his drawing and digital painting adventures at Visual Thoughts.